Dec 23 | “Stooping to Bethlehem,” (Sermon, December 23th 2018)

“But you, O Bethlehem of Ephrathah, who are one of the little clans of Judah, from you shall come forth for me one who is to rule in Israel, whose origin is from of old, from ancient days.â€

In January of 2017, students of the Jerusalem Ministry Formation course piled into our big bus and trundled down Salah-al-Din drive in East Jerusalem. We were to begin the day at Yad Vashem, the Holocaust museum, and then head south to the city of Bethlehem.

At Yad Vashem, there is a monument called the Children’s Memorial, a black box structure with many interlocking corridors hung with tall panes of mirrored glass. Throughout the building are tiny electric lights, which, when multiplied by the mirrors, give you the feeling of standing in a black sea of fireflies. The photographs of children who were murdered in the Holocaust are projected throughout, and their names read aloud.

It’s incredibly powerful, a bit devastating.

As I remember standing there, I wonder again how many King Herods we will allow as a species.

Afterward, we drove south into the hills. Modern Bethlehem, like its ancient counterpart, is occupied territory. The border wall splits the city in two and, more recently, curves around, making travel difficult, and preventing access to the tomb of Rachel to Christians and Muslims.

Honestly, Bethlehem probably hasn’t changed that much since the days of Jesus. It’s not a big town, and like many Palestinian towns it’s dirty and dusty, with a lot of crumbling infrastructure and terraced hills marked with scrub bushes.

We gathered in Manger Square. A gigantic Christmas tree, almost perfectly cone-shaped and bedecked with gold baubles and a dull grey star strung with lights, stood between the local mosque and the Church of the Nativity. This church, one of the oldest continuously used Christian churches in the world, was under construction when I was there, much of the inside hung with tarps and cluttered with scaffolding as people worked to preserve old frescoes and fix water damage.

I guess incarnation is always a work in progress.

The church itself is a rather charming mishmash of traditions. Each sacred space in the Holy Land is curated by a particular denomination, and the church of the Nativity is in the care of the Greek Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic churches. They have separate areas in which they worship, and all of the glory of the Orthodox tradition is everywhere – spectacular wrought iron, magnificent icons, gold and silver and silk, those distinctive, incredibly intricate silver and gold hanging oil lamps, fresh flowers and lace.

We were led toward what folks call “the grotto,†which is a tiny sunken chapel that, according to tradition, contains the site of the birthplace of Christ. It’s pretty clear to most archaeologists and biblical scholars that this is probably not actually the site, but such is the way of the Holy Land, a place so full of mystery and contention that each holy place, no matter its actual significance, becomes spiritually charged with the faith of the believers. I found that what continually inspired me most on that trip was the devotion of others. Human beings truly are stronger, in all things and all ways, together.

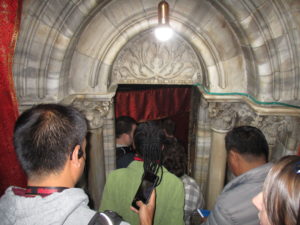

To access the grotto, you have to get in line. There are a lot of lines in the Holy Land, but thankfully in Orthodox churches, there are lots of things to look at while you wait. Beautiful gilt processional crosses and circles. Stunning icons in glass boxes adorned with strings of pearls and glass beads – offerings from the faithful. A poor box with a picture of Jesus and his name written in Greek and Arabic. And finally, the structure placed over top of the grotto itself, a marble archway with exquisite carvings, and a passageway with stairs leading down, its walls festooned with red silk embroidered with gold – for me, pretty suggestive considering I was descending to stand in the supposed echo chamber of the womb that carried the Source of all life.

Our prof, an affable Australian, chuckled and said he didn’t think it was intentional. I’m not so sure.

We entered the grotto and I found myself in a sizeable crowd. Icons and hanging lamps are everywhere. Two young Muslim women in hijab stood by the birthplace to pay their respects. Jesus and Mary are holy figures in Islam too. I felt privileged to have them there with us.

The supposed birthplace is marked by a silver star laid into the marble, and an altar is placed over top, with a space for the faithful to kneel and get close to it. The crawlspace itself is also festooned with icons and lamps, like the tiniest church you’ve ever seen. Nearby, behind a bronzed frame sculpted with images of wheat, is another little cubbyhole in which a crib has been laid: the supposed place of the manger.

You’re often warned when you go to the Holy Land that the things you expect to move you may not, and things which you don’t expect to move you may. The Church of the Nativity was definitely the former. Unlike many of the people I was with, I don’t feel particularly turned off by ornate churches, but this one left me feeling pretty empty.

What caught me up in Bethlehem was our trip to the wall outside Rachel’s tomb. Rachel, a holy figure for all three monotheistic faiths, used to be accessible to all, but now can only be accessed by her Jewish children. Standing before the wall, which is covered with gorgeous protest art in many languages, we were instructed not to get too close, because the wall had jets which could spray us with tear gas if we annoyed the guards in the tower above.

Most of us became tearful as one of the students read the story of Rachel’s death, which like Jesus’ birth occurred on a byway. Rachel dies giving birth to her last child, whom she names Ben-Oni, “son of my sorrow.†Despite her status as particularly beloved wife of Jacob, he refuses to honour the name she gives her son, changing it to Benjamin. In pain or denial, it doesn’t matter. The full truth of Rachel’s story is erased for a more convenient narrative.

And yet, as I stood there brimming with anger and sadness, my new friend Billy, a gentle gay man from New York, began to sing softly, “Let there be peace on earth, and let it begin with me.â€

Mary, unencumbered as of yet by this wall, travels to visit cousin Elizabeth, whose story is in some ways far more miraculous than hers, for what would startle you more: the pregnancy of a teenaged virgin, or a post-menopausal octogenarian? Elizabeth speaks this beautiful prophecy:

“Blessed is she who believed that there would be a fulfillment of what was spoken to her by her Lord!â€

Blessed is she who believed.

Standing in the walled up places of our lives, the occupied places, the disputed places, it seems impossible to believe in the truth of Advent, the truth of the coming incarnation, the truth of the fulfillment of all things. Standing before walls set with gas jets and soldiers with guns and fences with barbed wire and hearts bricked in for fear and protection, who among us can believe in the hope, peace, joy, and love we are promised?

Standing in the walled up places of our lives, the occupied places, the disputed places, it seems impossible to believe in the truth of Advent, the truth of the coming incarnation, the truth of the fulfillment of all things. Standing before walls set with gas jets and soldiers with guns and fences with barbed wire and hearts bricked in for fear and protection, who among us can believe in the hope, peace, joy, and love we are promised?

Few of us are called to be so steadfast as Mary, and so foolishly hopeful as Elizabeth. But maybe we can come to this by steps. And indeed, maybe that’s what Advent is about in the first place. In the Godly Play Sunday School curriculum, Christmas and Easter are referred to as “great mysteries†that the Christian needs time to enter, which is what Advent and Lent are for – getting ready.

The silver star in the Church of the Nativity, set into the marble, is not in the middle of the church for hundreds to cluster around. It’s in a grotto, into which you must descend.

Likewise God did not choose an empress or even a princess of Jerusalem in which to be enfleshed.

God chose Mary, in dusty contentious little Bethlehem, and her cousin, old Elizabeth, to bear the one who would announce the coming of Mary’s son.

And if of such humble matter God can make monarchs, how much more can God raise us up?

If you are ready, come tomorrow, and see what Love has done.