Archive for July, 2018

Today’s citations:

2 Samuel 11:1-15

John 6:1-21

Once again we return to our preaching series on kings and monarchs, and the kind of monarch we might imagine God or Jesus to be. So far, as we tend to do here, we’ve used the lenses of Scripture to explore the popular cultural understanding of what it means to be a king.

Today, listening to the story of David and Bathsheba, you may feel that the opposite is happening, and that our culture challenges the Scripture story.

It doesn’t sound the same in the era of #MeToo, does it?

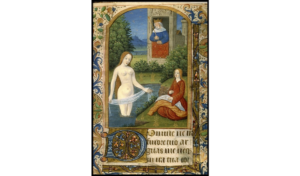

Source: Cornell University Digital Library

For many years scholars interpreted the story of David and Bathsheba as one of those classic “powerful guy gets screwed over by wily temptress.†This is certainly how many famous artists have depicted it, on canvas and on film. Bathsheba looks coy; bats her eyes; tosses her hair. She is the schemer who wants to get in good with the king, brazenly bathing on the roof where she knew he would see her, and then getting pregnant to trap him.

This is unfortunate, because the real story is actually a pretty radical story for a pre-feminist culture, and a scathingly self-critical one.

There are lots of clues. First off, there’s no throwaway lines in a Bible story. We should pay attention when we hear that ‘in the spring of the year, when kings go out to battle, David stayed at home.’ Things have changed for David. No longer fighting his own battles, he now sends his prize general Joab. Not inherently a bad thing, but the stories that precede today’s show us that David has stepped back from his rough-and-tumble roots and is beginning to engage in the more subtle art of statecraft with the monarchs of other nations.

Are the writers of this epic getting in a subtle dig at politicians and their ‘losing touch’ with the people? Possibly. They could also be showing us that the nation of Israel has grown from a people into an idea, something more abstract than a group of tribes.

And perhaps this is where the road to objectification leads.

So David is somewhere he should not be – not just home from battle but walking along his roof deck in the evening, and he sees a woman bathing.

Cultural note: Like short skirts and saucy banter, bathing on the roof is not an invitation. Everyone bathed on the roof in the evening in ancient Palestine. It was cooler then, and less busy. You do it on the roof because you can’t be seen up there, or at least not by the average person walking down the street. The only people who would be able to look down on you literally would be the ones who could do so figuratively, because they were rich and lived in a house that was higher than yours.

Here we see carefully laid bricks of meaning and metaphor. Bathsheba is not in control here. This story is about David’s abuse of his power.

So King David the peeping tom likes what he sees, and he asks about her. His servants tell him she’s a married woman. David knew Uriah, if not personally than peripherally, but that doesn’t stop him. He sends for her, and she goes.

Did the servants tell her why David wanted to see her? The text doesn’t say. It gives no indication that she even wants to go, but the king has sent for her so she goes, because that’s what you do.

Now if this story occurred in the #MeToo era, it would have been spun as a “he said, she said†story, because none of us know what happens in that room. However, the Bible is often quite candid about the feelings of women in its stories. And in this case, Bathsheba, like David’s nation, has become an idea – or in this case, an object – rather than a person.

We can’t honestly talk about consent when those concerned are a king and a subject, and not just a subject, but the wife of, for lack of a better word, an employee. At that point, intent doesn’t even matter. Those given power over others must be bound by higher laws than the average shmoe. A teacher and a student are not appropriate romantic partners. A doctor and a patient are not appropriate romantic partners. A king and a subject married to his employee are not appropriate romantic partners.

David should know that.

You can understand why I became annoyed at the heading assigned to this passage in my Bible: “David commits adultery with Bathsheba.â€

No. We have a better word for what really happened.

This is a betrayal of David’s God-given grace and power.

And it gets worse. Bathsheba becomes pregnant. Can you imagine how frightened she must have been? He could have had her killed. Instead, he attempts to manipulate her husband, and when Uriah turns out to be a far more honourable man than David, the king has him killed – in a cowardly, devious way.

Once Uriah is dead, poor Bathsheba, none the wiser about what really happened, laments, and then is brought into David’s house. Again, David is still in charge. And while she may have been relieved to know that she and her child would be cared for, it’s still a problematic marriage.

This touches on something that frustrates a lot of women seeking justice. There’s a lot of talk about how women have the power to ruin men’s lives by one “misunderstanding.†But this movement is about what happens when power imbalances exist and are maintained by the constellation of people around powerful folks. In some ways, Bathsheba’s story is easier to understand, because David’s power was absolute. To whom would anyone report his behaviour? David didn’t have an HR department! There weren’t newspapers that would line up for a juicy expose. No one had any recourse.

This is why God ordains prophets. As we’ll hear next week, Nathan is the one who confronts David with his sin, face-to-face. He advocates on Bathsheba’s behalf, because God never forces people to confront their own attackers.

Only our court system does that.

This is the first week where we see that David, beloved by God, is not a man subject to every temptation you’d expect. Having been given the world, he decides to take – to take his pleasure, to take someone’s autonomy, to take someone’s wife, to take someone’s life. Power does this to people; makes them hungry for more, more, more.

So once again, let’s contrast kings of earth with our king of heaven.

Where David takes, Jesus gives.

Jesus chooses not the royal palaces of Herod, but an outdoor field in Gentile territory; not rich robed officials but the ragged poor; not roast lamb but barley loaves and fish, the bread and meat of the poor.

What’s fascinating is that for a moment, the crowd fully understands who he is. They use a special Johannine phrase: “the prophet who is coming into the world,†and they try to make him king.

And Jesus fully renounces that.

He wants nothing to do with earthly power. He knows it is a dangerous thing.

Instead of seizing earthly power, which is but dust, he reminds the disciples who they really belong to. They see the veil of time torn asunder, and they’re back in Genesis, at the beginning, for pneuma, the word for wind, is the same as the word for Spirit. The pneuma blows over the face of the deep, and Jesus walks across it, and speaks not the bloodless English phrase, “It is I,†but Eigo eimi, I AM.

I AM; do not be afraid.

And before they can take him into their boat, they are brought to their destination. They cannot tame this king, and yet they can travel with him, touch him, hold him, at least for a little while.

The world is full of those who would take, and break, and gorge themselves on wealth and pleasure at the expense of others as though they were gods. Let us, like Nathan, never be afraid to speak out on behalf of those who are silenced, and like the disciples, remember who we really are: part of a web of life, a web of love, that dies and rises together, or not at all.

Citation: Romans 2:4b-11

I did some creative snipping for clarity’s sake so I’ll post the chosen passage below.

Do you not realize that God’s kindness is meant to lead you to repentance? But by your hard and impenitent heart you are storing up wrath for yourself on the day of wrath, when God’s righteous judgement will be revealed. For he will repay according to each one’s deeds: to those who by patiently doing good seek for glory and honour and immortality, he will give eternal life; while for those who are self-seeking and who obey not the truth but wickedness, there will be wrath and fury. There will be anguish and distress for everyone who does evil, the Jew first and also the Greek, but glory and honour and peace for everyone who does good, the Jew first and also the Greek. For God shows no partiality.

This passage follows a well-known “text of terrorâ€: Romans 1:18-27, which has been used to clobber the queer community for too long. What’s interesting about this, and about many similar texts of terror, is that many of those who use it as a cudgel ignore not only the context but everything around it. What follows it is a warning from Paul that those who condemn should not stand in judgement, for they too are guilty of sin.

Not an ideal response for our purposes, but not what you might have expected if you’ve had this passage hurled at you at some point.

The liberal church is rightly vigilant about the way talk of sin can turn abusive, but as we’ve seen in the recent past, civility in discourse can only get you so far. Eventually, someone needs to stand up and name the evil, or we risk standing by while it flourishes.

It is possible to call out sin in a way that demonstrates care for someone’s soul. Unfortunately, the kind of churches who make use of this often do so not only unkindly, but about issues that are more about culture than Christ, while remaining silent on issues that the Bible is quite clear about, like justice for the poor and the oppressed.

We may or may not share Paul’s conviction that the wicked will be punished by God in or outside of this lifetime. We can be sure, however, that God cares deeply about the way we walk in the world among our fellow creatures. We dare not be resentful of the forgiveness that pours forth from God’s heart for others, for there will surely come a time when all of us will need it.

Citation: Mark 5:25-34

This story occurs in the middle of another healing story: that of Jairus’s twelve-year-old daughter raised from the dead. It is clear that they are linked, although scholars have different opinions as to how. What both stories do show us is that Jesus cares deeply for the health, well-being, and empowerment of women.

The woman with the haemorrhages, like all those healed by Jesus, is not just someone with a painful and embarrassing problem. All healing stories are about so much more than magic. According to the Levitical laws, this woman’s problem made her perpetually impure and therefore unable to participate in the life of the community. No one was even allowed to touch her. Likewise, she was not allowed to touch anyone, but most especially not a holy man like Jesus. But she is so desperate, in so much pain (surely not just physical but emotional and spiritual as well) that she doesn’t let it stop her. Thinking he won’t notice, and that it’s less spiritually harmful than touching exposed skin, she touches his cloak. At her most vulnerable, her most isolated, she reaches out…and it works!

But Jesus feels her presence.

Imagine the bravery it would have taken to come forward and admit, “Yes, I touched you.†The crowd would likely tell Jesus about her problem, and she would have to deal with whatever wrath or scorn came her way.

Instead, he calls her “daughter,†and then proclaims that it is not his great power, but her great faith, that made her well. Then, confusingly, he tells her to go in peace and be healed of her disease. Hasn’t that already happened?

Jesus speaks these words not for her, but the people around her. He validates her action, which would have been condemned by others for its impropriety, and then he tells them that it worked. And therefore, of course, they are free to welcome her back into the community, to work, worship, and be well among her family and friends again.

Here, we see a Messiah who is happy to use his privilege to help women in need, no matter the cost.

Today’s citations:

2 Samuel 7:1–14a

Mark 6:30–34, 53–56

Good morning, saints – is how Pastor Laurie at Spirit of Grace Church in Oregon greets parishioners in worship. I am glad to be back among you, and glad to be back to our preaching series on kings.

As we planned our recent trip to Oregon, my husband Paul and I decided to forego the indignities of air travel and take the train. It left us with lots of time on our hands, during which time I read some articles on Twitter.

One of them, written by Jerry Useem from The Atlantic, was about power – political or social power – and what it does to the human brain. It was quite fascinating. Historians and now several scientific studies have shown that power causes a form of brain damage; in particular, to the parts of the brain which manage empathy.

This might be no great shock to you, but to have it scientifically proven is pretty astounding. The article interviews Dacher Keltner, a UC Berkley psychology professor who conducted many of the cited experiments and lab work. From the article, quote, “Subjects under the influence of power, [Keltner] found in studies spanning two decades, acted as if they had suffered a traumatic brain injury—becoming more impulsive, less risk-aware, and, crucially, less adept at seeing things from other people’s point of view.†Another expert, neuroscientist Sukhvinder Obhi at McMaster University in Ontario, discovered in a brain scan study that, quote, “power impairs a specific neural process, “mirroring,†that may be a cornerstone of empathy.â€

Mirroring is a more subtle form of the mimicry that happens between the powerful and their inferiors – say the way people laugh when their superiors laughs, or tense up if we can feel that person is tense. Mirroring actually happens in the brain itself. When we see someone perform an action, the part of a healthy brain associated with that action lights up in response. In the brain of someone who is powerful, however, it was shown that this response doesn’t occur.

This gives us a specific neurological reason for what Keltner calls “the power paradox,†the strange tendency to forget all of the social tools one used to gain that power.

It’s possible this occurs because when we are powerful, we use less energy trying to convince others to do what we want, and since we are in charge of more people this can help us become more efficient. But that pride, that hubris, has many terrible consequences.

The bad news is that Dr. Obhi, the neuroscientist, discovered that explaining the idea of mirroring to people before a second test did not change their ability to empathize. The good news is that Dr. Keltner, the psychologist, found that in some cases, a person recounting a time when they didn’t feel powerful could help keep them in touch with reality.

You can imagine that a regular person who becomes very powerful could easily lose touch with the world, but just imagine someone who has always been powerful, and how difficult it would be for them to rearrange the way they had always seen the world.

Actually, we probably don’t need to imagine that hard.

Knowing this, don’t you think it’s amazing that God, the most powerful force, the source of all life, is not only able to connect deeply with all of creation, but wants to?

King David, who in the passages before today’s reading has seen and celebrated God’s awesome power while traveling with the Ark of the Covenant to his home, now feels that it deserves a grand house of cedar rather than a tent. This is a normal response to his good fortune. He feels grateful and wants to share his blessings with God. At first, Nathan sees nothing wrong with this, but later God corrects him. God tells Nathan to remind David about the great salvation of the people from Egypt, and adds that there has never been a commandment for a house. God does not need a house from David, for God’s blessing on his line is unconditional and therefore impossible to return, which keeps things in balance. God then reminds David about his own roots as a shepherd, a seventh son, a nobody. God anchors David in his humble past, then lays on David the responsibility of producing a son who has the spiritual strength to create a house for God, a concrete symbol of that special relationship, in the future. David’s job is to always remember the easy trust he has had in God so far. Modeling that for the people is the most important thing. The grand gestures can come in the next generation.

We move from King David to King Jesus, and we see a shift. Jesus seems immune to the temptations of power. He refuses the offers from Satan in the wilderness. The section missing from the Gospel reading this morning is the story of the feeding of the five thousand, and then his walking on the sea. That last one, and the stilling of the storm, are the only non-healing or exorcism stories of Jesus showing his power. He rarely shows power for its own sake, choosing instead to feed and heal people, literally using power to bring others closer to him and to each other. In fact, in the Gospel of John there is even a story where the people try to make Jesus king by force, and he takes off to the mountains to be alone.

Mirroring, then, seems to come naturally to Jesus as he gains power, which is the exact opposite of what should happen to a regular human brain. And maybe this is only one way of how God chose to be incarnate.

Perhaps we could even say that in Jesus, God was choosing to “mirror†us. Perhaps God knew that, by doing so, our relationship could finally go both ways.

How incredible is that?

God eschews sovereignty, pushes away a royalty that oppresses or bullies in favour of trying to be more like us in order to love us better. God, loving us as deeply as a parent, was able to see the best of humanity and therefore took that on to mirror us and teach us – and yet also chose to do so in a very humble form, the form of a poor brown man in an occupied land, a man who like all of us started out as a defenseless baby. God wanted to reach out to the most vulnerable and therefore mirrored them. God chose solidarity with dust.

How do you even respond to that kind of love?

Accepting it is the first step, and the difficulty of doing that should not be underestimated. It’s the work of a lifetime.

But there is more to do.

Accepting love gives you real power, the kind of power that can last or languish. You can only really accept it if you’re willing to let it change you.

And maybe that looks like remembering our roots as fragile things who need love, who are worthy of love, who are only here by love, for love.

When I was at Spirit of Grace I met a wonderful man called Fliegel. We talked at length about the world and its many problems and hurts, and particularly about his fears and frustrations for his own country.

“I think the United States needs to get rid of this idea of independence,†he said. “I think what we need for the new era is a declaration of interdependence.â€

Don’t you love that?

We are all part of a sacred web of life, and there’s no way to opt out of it. If we are called to be more like Christ – or like God in Christ – then maybe we need to try to mirror each other more. Maybe we need to mirror the earth more. What would it be like to mirror the earth in your life? What would it be like to be solid like a stone, or nonviolent but gently cajoling like water, or hopeful like a lark in the morning, or wide open like a prairie sky? What would it be like to gather wisdom, to gather the building blocks of a whole new self, from the creatures all around us?

Maybe like falling in love, every day.

Imagine that.

Citation: Esther 1:1-5, 9-20

Vashti is the kind of character that makes some of us want to get up and cheer. Her story may even sound a little familiar – if you’re a Shakespeare fan! This story was almost certainly in the Bard’s mind as he penned the famous final scene from The Taming of the Shrew. Vashti, like Godot, is one of those famous folks who is famous despite never being seen or heard from in the story which contains her.

There’s something refreshing about this moment full of pomp and ostentatious wealth being popped like a balloon because one woman refused to be objectified. This one act of defiance has made Vashti a hero for many women, Jewish and Christian alike, and in the era of the #MeToo movement she’s a most appropriate matron saint to women tired of being sexualized against their will.

Unfortunately, we don’t know what happens to Vashti after her husband’s childish display of masculine fragility. Since he’s rich he can fix his problems by throwing money at them, and so he disposes of Vashti and seeks out a new queen by – no kidding – arranging the ancient version of a beauty contest. The winner, he decides, will be his new queen. Lest the reader despair, his new wife is Esther, whose methods may be more cunning than Vashti’s, but proves that she too is not afraid of her husband, using her privilege and power in court to save her own people from annihilation.

Both Vashti and Esther show us that women have many ways of asserting themselves. Over the course of a lifetime, we may find that some days it’s more effective to be clever and cajoling like Esther, and some days it’s best if, like Vashti, we choose open defiance, refusing to participate in our own oppression no matter the consequences.

May we all embody both the courage of Vashti and the cunning of Esther.

Citation: Genesis 16:1-14

At first glance, this is one of those stories that may appear to have little to say us today. Abram and Sarai have no children, which would have reckoned to them as a curse among their people. God has promised Abram children in the previous chapter – and has also promised that Abram’s descendants will be slaves in “a land that is not their own.â€

This sets the stage for Hagar, the Egyptian slave given to Abram as another wife by her mistress Sarai.

The bearing of children for someone else was common in family units. We see it in other Biblical stories. What’s painful about this story is the treatment of Hagar by both Sarai and Abram. You’ll notice that they never refer to her by her proper name, and do not speak to her, only about her.

The angel of God is the one who first speaks Hagar’s name, the first one to truly see her. Although it seems cruel to tell her to return and submit, we could see this as a gentle chastisement against her scorn of Sarai. The angel also adds that Hagar’s son will be Ishmael, which means “God will hear†– a sign that God sees and knows Hagar in her pain. She’ll also bear not just one son for Sarai but many children, for herself.

Here comes the most beautiful part of the story. Hagar, named and seen by God, names and sees God herself. The name “El-roi†is commonly translated “The God who sees me.â€

To name something is to claim it.

Hagar the Egyptian slave girl trusts in God in a way that Abram and Sarai have not been able to do yet. Fittingly, it is in the next chapter that they receive new names, Abraham and Sarah. Only after Hagar, the abused one, is seen and blessed do these heroes of the faith receive the treasure God has promised.

To an audience accustomed to seeing the Egyptians as enemies, this was a radical story of a God who could enfold all nations, all creatures, into Her embrace.

Today’s Citations:

2 Samuel 5:1-5, 9-10

Mark 6:1-13

So far in our summer series on kings, we’ve explored what kind of ruler Jesus is: a ruler who is a refugee, a prisoner, a prophet, someone who shows us great power by sharing it with others.

And up until this week, for the most part, King David has proven to be not unlike King Jesus, in that he enjoys God’s favour and the love of the people. Today, we hear the story of him anointed king by the people. Now we actually heard about Samuel anointing David already – God clearly saw David as a king long before the people accepted him. But now the people are finally on board. They have accepted God’s chosen one, and unlike Saul, we know that David trusts God completely. The people say that David, who once kept sheep, will now keep the nation as sheep. This was a popular metaphor for kingship at that time, but it’s also an approval of David’s whole person, because even though folks saw kings as shepherds, being a shepherd not a glamorous job.

Quick sidebar: I had some fun thinking of metaphors we could substitute for this today. Our king is like the fast food worker who feeds us quickly and affordably when we are hungry and poor. Our queen is like the jewelry store worker who guards us, her jewels, from thieves. Our emperor is like the care aide who provides for our most basic needs no matter how tired she is. Our ruler is like the janitor that makes sure we stay healthy by keeping things clean and working properly.

These are all jobs that many people take for granted but that none of us could do without – just like being a shepherd was then. And we are hearing the people tell David that they welcome that part of who he is, and celebrate it.

And then we have the story of Jesus rejected in his own hometown. Here, his being a carpenter is not celebrated but mocked. “Who does he think he is?†they say. They also call him “the son of Mary.†Back then, almost no-one referred to men as sons of their mothers; they would call them the sons of their fathers. To call him “the son of Mary†was another way of mocking Jesus.

It isn’t just the Gospel reading that shows us the differences between the triumph of David and the shame of Jesus. For me, there was an unexpected moment of discomfort in the naming of the place of David’s anointing.

David is crowned at Hebron, which is in the West Bank in the Holy Land.

I have been to Hebron. I was there as part of a course a year and a half ago. It’s the kind of place that you lie about going to. When you are coming home from the Holy Land, you are asked many questions about why you came, what you did there, what and who you saw, and even who you are and what you do back home.

All of us were coached on how to handle that interrogation. We were given a list of places to tell security we had been to, places which were acceptable for Christians to visit, like Bethlehem. Hebron, we were told, was not a safe place to admit to having been to. We were told to only say we had been there if we were asked directly.

Hebron’s a dangerous place. The tomb of Machpelah is the jewel of Hebron, the oldest continuously used prayer space in the world, which houses the tombs of the fathers and mothers of the Jewish faith. It is also so holy to Muslims that it’s an acceptable place to complete the hajj pilgrimage if they cannot go to Mecca. It’s also been the site of many massacres, most notably in 1994 by a Jewish-American extremist and his followers, who opened fire on worshippers, killing 29 and wounding 125. Not long after that event, armed guards and metal detectors were installed outside and inside. The building was split into a Jewish prayer space and a mosque with two separate entrances, and the tombs of Abraham, Sarah, Jacob, and Leah within are guarded by Israeli Defense soldiers with assault rifles. You have to be very careful when taking photos of the tombs not to include the soldiers in them.

In the mosque, where many pilgrims greeted us with smiles, we met the imam, who told us that Muslims were regularly subjected to searches, and sometimes even barred from sections by the Israeli authorities.

Before we went into the mosque (it took about twenty minutes to get clearance to enter), we hung about one street which had a shop that offered gifts and free sage tea. Children called to us to invite us over. Men tried to sell wallets and woven accessories on their own. Other than that one street, though, the portion of the city we saw was eerily silent – very unusual considering how close it was to such a holy site. A few kids sat on steps and watched us warily. Stray cats searched through garbage. I took photographs of protest graffiti on walls, including a beautiful white dove with an olive branch in its beak. When the Muslim noon prayer time arrived, the songs of the muezzin, who call Muslims to prayer over crackly loudspeakers, erupted all over town simultaneously, louder than we’d ever heard in the other places we visited. The dean of the college offering the course told us this was a sign of resistance against the Israelis, many of whom make noise complaints to the police against them.

Before we went into the mosque (it took about twenty minutes to get clearance to enter), we hung about one street which had a shop that offered gifts and free sage tea. Children called to us to invite us over. Men tried to sell wallets and woven accessories on their own. Other than that one street, though, the portion of the city we saw was eerily silent – very unusual considering how close it was to such a holy site. A few kids sat on steps and watched us warily. Stray cats searched through garbage. I took photographs of protest graffiti on walls, including a beautiful white dove with an olive branch in its beak. When the Muslim noon prayer time arrived, the songs of the muezzin, who call Muslims to prayer over crackly loudspeakers, erupted all over town simultaneously, louder than we’d ever heard in the other places we visited. The dean of the college offering the course told us this was a sign of resistance against the Israelis, many of whom make noise complaints to the police against them.

Hebron is not a glamourous place, the kind of place that feels utterly alien to a Western city kid like me.

And while today a king like David would never be crowned there, Jesus could be. I believe Hebron, atmospherically, would have felt familiar to Jesus and his disciples. Imagine going into a creaky old house in the heat of summer after many weeks with no rain, and the first thing you smell is gunpowder – not just a little but a lot, a thick heavy cloud. That smell’s going to change how you move around in there, right? That’s kind of how it felt to me, and that gave me a lot of sympathy for those who reject Jesus at Nazareth. In the text we hear that some “took offense†at Jesus. Why? What’s so offensive about healing? Well, in a powder keg town, you want to keep your head down. Here in Vancouver we can go out to protests and make a fuss about things that are worth fussing about – and even some that aren’t!

But in a powder keg town, if you don’t keep your head down…boom.

All it takes is one match, one rock, one healer to light an empire’s fuse.

Nazareth was a small town. People would have grown up with Jesus and his family. They cared about him, and here he came, preaching and teaching and healing right out in the open. And then, as if that wasn’t bad enough, he started teaching his followers how to do that stuff too. This was now an organized effort – even more dangerous.

This week’s story is here to remind us that following this king has consequences. Throughout most of history people could only get in trouble for not following kings. This is completely upside-down! And yet that is in keeping with our upside-down king, who chooses children and outsiders to make up his royal court. That’s good news for some, bad news for others, because for some of us it takes a conscious effort to become outsiders, while others have always been and always will be outsiders.

If this sounds frightening, don’t worry. We don’t do it alone. Every justice movement that has brought good to the world only accomplished its holy work because people did it together. And we do our work together. And we are cared for better than any other servants, because God our ruler not only sends us out to harvest what She herself has planted, but invites us to come inside Her house and be fed – and not even in some dingy servants’ quarters but here, together, at Her table.

Like family.

The Resistance Lectionary is a writing project I decided to start after reading a zillion awesome Twitter threads and, most important, having wonderful conversations with a new friend who is searching for how to embody her faith in a world where Christianity is struggling to figure out who it belongs to.

After many years of feeling completely at odds with the Bible, I encountered it in a far more intimate way in seminary and discovered an incredible story that was so much more than I was led to believe. As usual some stories are elevated and repeated over and over while others go unnoticed and unknown. After the 2016 election, it became more important to me than ever to be loud and proud about the kind of Christianity I grew up with – the Christianity that showed up and stood up for the lost and downtrodden and oppressed, the Christianity that wasn’t afraid to go toe-to-toe with the law and propose the unimaginable, the Christianity that made its home among the societal rejects and proclaimed them not just “children of God” but holy and beloved.

I’ve collected passages from the Bible that I believe demonstrate that kind of radical boundary-breaking scandalous faith through stories and characters that challenge every armchair theologian’s response to the text which has influenced so much of Western culture, and will post short reflections (200-500 words each week).

Here is my first.

PART 1: “WHAT DOES THE LORD REQUIRE?”

Citation: Micah 6:6-8

We’re at Ground Zero of the social justice passages with this gem. We quote it, we tweet it, we sing it. It’s one of those passages which seems unfamiliar to many who cry against the so-called culture wars, demanding personal purity ahead of solidarity. It lays many of our high-minded, privileged debates about appropriate and civilized behaviour to rest with a real mic-drop moment: Do justice, love mercy, walk humbly with God, simple as that.

It’s a prooftext those of us who hate prooftexting can get behind.

But how often do we look at the whole thing? The part we quote most comes at verse 8: “He has told you, O mortal, what is good…†But we don’t often look at the section before that, the original question of what one must do for the liberating, boundary-breaking God and the proposed responses of sacrifice and offerings.

We children of the twenty-first century West are far removed from temple-sanctioned blood sacrifice (although we could argue long into the night about whether we have truly evolved beyond the general idea of blood sacrifice). However, there are still pseudo-sacrificial performative acts that we seem to believe will make us “good†before God and yet may not be what God truly wants from us.

Knowing this, perhaps we can reimagine that first section thusly:

“With what shall I come before the Lord,

and bow myself before God on high?

Shall I come before God with repressed sexuality,

with religious patriotism?

Will God be pleased with thousands of Scripture quotations,

with tens of thousands of calls for civility?

Shall I exchange politics for faith,

anger at injustice for inner peace?

God has told you, O child of earth, what is good.â€

That last verse, though, that can stay as is. Don’t you think?

Today’s citations:

2 Samuel 1:1, 17-27

Mark 5:21-43

Now that church school is over we welcome the children of St. Margaret’s to join us for our preaching series on kings. The grownups may notice that I’m changing my tone a bit to be more accessible to our children.

This is our fourth Sunday working through the story of the first kings of Israel, Saul, David, and Solomon. We’ve noticed so far that many of the stories are given to us in chunks with big gaps.

And guess what? Today there’s another big gap!

The Hebrew Bible passage today is David’s lament over Saul and his sons, killed in battle. A lament is a way to express sad feelings – usually in song. So David sings a song about how sad he is that Saul and his sons are dead.

Now this might be confusing, because Saul and David are rivals. We learned that the people of Israel wanted a king, and though God didn’t think it was a good idea, she chose Saul to be their king. But Saul wasn’t a very good king, and didn’t listen to God, so God decided to make David the new king.

Saul was not pleased with this, and he was especially not pleased with the fact that David and his son Jonathan were best friends! So Saul tries to kill David, but David always escapes.

That gap I talked about earlier includes David trying to escape from Saul, while becoming a famous warrior. Unlike Saul, David always listens to God. Unlike Saul, who spoke to God only through the prophet Samuel, David can speak to God directly, one-on-one – and he does whenever he’s about to do something important.

David is also shown to be a good person. Twice in the story, he spares Saul’s life even though he has a chance to kill him, while Saul forgives David each time…and then seems to forget all about it. Saul also fights with his son Jonathan, who tries to tell Saul that David has never done wrong, but Saul won’t listen.

One day fate catches up to them, and Saul and Jonathan are killed. David cries for his best friend…and Saul, and sings about how brave they were.

David’s heart is full of kindness and mercy toward others, and trusts totally in God. In these chapters, David is a role model, showing us how we should be with God.

What’s interesting, though, is that David does not stay perfect forever. We will hear about that story in the next couple of weeks.

What happens to the good king David? It might have to do with power.

See David isn’t born a king. He is born a shepherd, the youngest of the sons of Jesse. When Samuel asks Jesse to bring his sons to Samuel because one of them will become king, Jesse doesn’t even bring David! He thinks that there’s no way David would be the one. And yet, David is the one.

And of course many of us know the story of David and Goliath. David goes out to meet the giant Goliath [and help me out, everyone].

Does he go out wearing armour? No! Saul tries to put armour on him and it’s too heavy, so he takes it off!

Does he bring a sword to kill Goliath? No! What does he bring? Five stones from the riverbed, for his slingshot. And he doesn’t even need five! The first one brings Goliath down.

David is not powerful on his own. God is always with him. But you’ll notice that once David becomes king, he does well for a little while, but eventually falls victim to pride and greed.

This is different from what happened to Saul, whose sin was never really trusting God. David trusts…but maybe the power started to go his head.

David is at his most generous and kind when he has no power, on the run from jealous Saul.

Not everyone who has power is unkind, just as not everyone who has no power is kind. But when we know what it’s like to be weak or helpless, it’s often easier to help others who are. History shows us that the more power a person has, the more they want. And the longer someone stays powerful, or rich, or celebrated, the harder it is to remember a time when they weren’t. And if you have always been those things, it’s even harder.

You can see this with all of those isms: racism, sexism, classism, ableism, nationalism, homophobia. All of these things are ways for one group to say they’re better than another, to say that the other group is stupid or evil. They all come from one group having power over another, and trying to hold it instead of letting go.

Jesus, a king greater than David, shows us how we should really hold power.

In the story, a kind person, Jairus, begs Jesus to save his daughter. I say he’s kind because back then, a lot of people believed that daughters were not as important as sons. Jairus loves his daughter so much that he begs Jesus to save her, even though the people with him think there’s no point because of how sick she is.

Jesus being Jesus of course agrees to help – by using his healing power.

Then we get the story about the woman with the hemorrhage. A hemorrhage is a constant flow of blood, which sounds bad enough, but it was even worse. Not only had this woman spent all her money trying to get better, but the ancient laws written in the Book of Leviticus wouldn’t allow her to be a full member of the community because of her illness. Desperate, she sees Jesus, and her faith in his power is so strong that she decides to touch his clothes. This was a risky thing for her to do. Jesus was a rabbi, a holy man, and again, according to the ancient laws, a sick woman like her should never touch him. It sounds mean, but people believed back then that you had to be healthy and ready to do or touch something holy, because if you weren’t you could get hurt: the ancient version of touching a hot burner.

But the woman touches Jesus anyway, maybe thinking he wouldn’t notice.

Again, Jesus being Jesus, he does notice.

Listen to the words the story uses: He became aware that power had gone out from him.

Jesus in this story is like one of those big transformer batteries – humming with power. And this woman reaches out, and a little bolt of goes from him to her, like lightning hitting a tree. Maybe it felt that way to her too. All of a sudden she stops bleeding.

Jesus has so much power, but he’s happy to walk through a crowd letting anyone touch him. But even though the disciples tell him nothing happened, he notices, and looks around until the poor woman comes forward. She’s afraid because she touched a holy man, and thinks he won’t be happy, because a holy man knows those holy laws.

But he doesn’t scold her. He congratulates her for her faith, and says it has made her well.

It sounds funny: the story already said she was healed, but Jesus says she’s healed again.

Maybe this let everyone else know that she was healthy again, and could come back.

All kings have the power to divide and unite.

And of course, the story doesn’t end there, because then, after Jesus willingly shares power again: power enough to bring a little girl back to life, giving her the chance to rise up and be known as one who conquered death. I see this story as a feminist story, if you can’t tell. Little girl, get up – rise up, claim yourself.

This is what King Jesus wants for all of us – to come to him with all of our fears and hurts, to not be afraid to touch him, to come to him even when we think it’s too hard or too late to do so, because it never is, never.

Any king can be cruel, and any king can be kind. What makes King Jesus special is that he came not to be served, but to serve.