Archive for June, 2019

I read this article recently and it brought me back to earlier days when I would lie around devouring comic strip compilations. I loved them: Garfield, Calvin and Hobbes, B.C. (my grandfather must have had twelve of those in paperback), and that mainstay of ’90s working women, Cathy.

I was surprised to read that younger women looked at Cathy with such disdain. I always rather liked her.

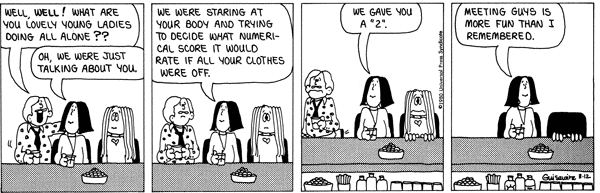

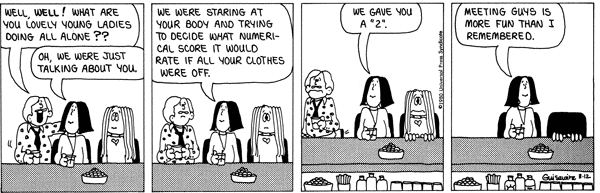

Going back and re-exploring old strips, I can see where the disdain comes from. Cathy these days does seem pretty dated. She wasn’t exactly a paragon of feminism, although she did try. Her relationship with Irving is probably the most frustrating part of the series. I don’t know much about how people reacted to her marriage to Irving, which occurred in the mid to late 2000s, but it annoys me today. I also find him grating today in a way I didn’t before. Here’s some stuffy emotionally constipated nonsense balanced against man-child phases over sports or other women.

There were plenty of strips where she railed against the fashion industry, or her mother’s tiny dreams for her, but she was regularly crushed under the machinery of the patriarchy, or simply her own insecurity.

Reading it again, I found that I still had some love for her, especially after reading this from Cathy Guisewite’s website. I can’t believe she managed to create a cartoon empire having never actually learned to draw. And I agree with Guisewite that her character has real resilience. As neurotic and messed up as she is, she pushes back against her limitations every single day.

I resonate a lot with that.

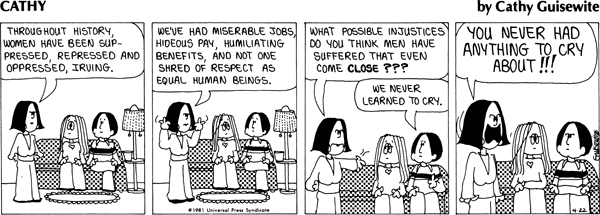

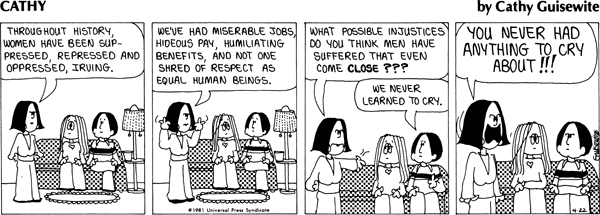

Then I read a little further, and damn but if girl can get a real laugh out of me every so often.

TELL ME THAT COULDN’T HAVE BEEN WRITTEN LIKE A WEEK AGO.

The only difference is that you can tell that the reader is meant to empathize with Cathy, not Andrea. Today, there would be 75K retweets from folks who had just changed their avatars to Andrea’s guileless grin.

Don’t you adore the three thousand pounds of ’70s smashing into you through the power of that blonde dude?

There were a few strips like this in the early days when Guisewite was younger and punchier. This one was by far my favourite.

Again, you can see from the art that this was early in her career. Believe it or not, the lusciously coiffed dude on the end of the couch is Irving, he of what I once believed was the perpetual crew cut. The first few strips, actually, involve Cathy trying to get up the guts to tell him what a jerk he is, but of course she never can.

And I feel for her even more in those!

Look at her face in the last panel. She feels Andrea’s rage, but also feels unable to communicate it. And in this way, I think she captures a generation very well, “a generation of women who came of age in a brand new, exciting time for women,” and yet some of whom were Cathys and some of whom were Andreas.

Both Cathy and Andrea have careers, but only Andrea, especially in these early days, seems capable of speaking out about the bullshit she sees around her. Cathy, who shares most of Andrea’s beliefs, is nonetheless having to rebel against everything she has been raised to be with every step she takes.

That’s why the in-depth explorations of her relationship with her mother are so interesting to me. Cathy has resilience and drive and the power of the feminist movement, but the world has shifted and she is forced into a totally new universe where she feels she has to balance her trained civility, innuendo-driven communication, and passive-aggression against a strength borne out of the knowledge that despite how infuriating she finds her mother, Anne is a) a survivor and b) loves her more than life itself.

I see so much of me in Cathy, perpetually struggling against the problematic coping mechanisms she has while trying her best to bust ass all across the kyriarchy.

But I think the real reason I love Cathy is that, when I was growing up, I saw so much of my mum in her.

Cathy gave me a vocabulary for the struggles I saw my mum go through: the perpetual battle to maintain a desirable weight, the pressure to work twice as hard as the men around her to impress half as much, the search for a life partner (although my mum was never as needy or desperate as Cathy), and the strong feminine bonds with friends which were mostly based on sharing complaints about any of the above challenges.

Like Cathy, my mum was a working dynamo, overachieving morning, noon, and night to be seen and recognized. Neither of my parents grew up with much money, so when they divorced my mum knew it was up to her to pull us through (since my dad, God rest his beloved soul, really wasn’t good with money). She’s always been ambitious, but there is so much of my childhood that, when I look back on it, was the way it was because my mum was determined that I would never have any need to worry. She was incredibly warm and accepting, and yet a real task-master when she put her mind to it. She was also determined that I would be the first in the family to go to university, and was adamant that I pursue the degree that I wanted even if it seemed “fluffy,” because education was its own reward. When I decided to take what felt like the ludicrous steps toward a Masters of Divinity, she gave me, with no questions asked, four hundred dollars to supplement what I scraped together for the year before I could qualify for work study and bursary assistance. She never stopped encouraging me to continue with school; I often joke that when I came to her with my master’s degree in hand, she said, “So…PhD?” (It’s not really a joke).

Unlike Cathy’s mother Anne, my mum has never pressured me to marry or have children. She adores my husband and I do know the latter would make her very happy, but she has always only wanted my own happiness. It was clear that, even when she was driving me crazy, a good and happy life for her child was her ultimate intent. I always trusted her wholeheartedly.

That, too, I see in Cathy and Anne’s relationship.

So here’s to you, Cathy, even though you married a schmuck. You finally got what you wanted from the start, and that’s something to cheer for.

This is the second and final installment of my first set of writings on my journey to ordination. Part I can be found here.

PART II: AW HELL NO

As my heart soaked in music, my soul became refined like ore by the liturgy of the church. The rhythm was always the same. It lulled me, knowing what would happen next, felt safe and warm like an old winter coat.

When I returned to church after a few years of spiritual wandering, it was so easy to put that coat on again. But now, growing out of the earth laid there by my environment, my mother, and my childhood, there grew seedlings of my own understanding, new wisdom gained through the everyday struggles of a privileged life.

I rediscovered God after a difficult period of loneliness, bullying, and great uncertainty, appropriately enough in the beautiful city of Norwich, the home of St. Julian, mystic and anchoress, the first woman to write a book in the English language. Julian wrote rhapsodically about a God in whom there was no wrath or malice, and a mother Christ who nursed us with the milk of the Eucharist.

It was here, in the midst of my sorrow and terror, that I was gathered up into an embrace that my body and soul remembered but my mind had long forgotten. In the glow of my own revelation of divine love, I realized that my whole life would not be enough gift to thank the one who rescued me…but it would be more than accepted by Her. It would indeed be treasured.

As I matured in my newfound faith, I discovered that I wanted to share this amazing reality with others, for it was not only for me. All around me were people not only searching for meaning, but who had encountered a hostile church, one that robbed them of their humanity, which bullied them just as I had once been bullied, as a child and an adult.

I had never known that kind of church, and it filled me with sorrow and rage that something I had found to be such a sanctuary could turn around and defile the glory of a human being fully alive. It became imperative that I do as much as I could to show people a different way – not just of church, but of Christianity. It became imperative to demonstrate that this kind of Christianity was not something I had just made up. It was shared by many. It had a history.

One beautiful summer day, as I was walking home, I had a conversation with myself about how I could possibly serve such a glorious God. Ideas came and went, until I laughed inwardly.

Oh, what – you want to be a priest now?

A long long long inner silence followed.

Then, a voice which was inside me and yet outside as well:

Why not?

And another long silence.

Which I’ll fully admit was succeeded by Aw HELL no.

That was the beginning.

The space between that first question and the moment when the Bishop and my colleagues laid hands on me was ten years.

A lot of people are quite surprised when I say this. Others almost appear relieved. Yes, there is much wandering required. Also, pain and suffering.

And great joy.

Certainty, which I believe to be the true opposite of faith, should be rare. Unwavering confidence should be rarer. Rarest of all should be the idea of that holy hands-on moment as a prize to be won.

It is no prize. It is no reward, no treasure, no triumph.

It is something beyond description, something I only received through tears and terror and “sweat like great drops of blood.â€

Some argue that it brings about an ontological change; some say that whole notion is self-important folly.

I have Anglo-Catholic sensibilities, so I happen to agree there is an ontological change in a person when they have been ordained. But it doesn’t make them better than anyone else. The Christian heart finds itself drowned in baptism and scored with fire in confirmation, and every Christian is called to struggle and pray for the kingdom to come, for when the kingdom comes fully there will be no need of clergy or institution or boundary between us, for all will sing the song of Love made incarnate and crowned emperor and, like Jeremiah writes, no longer will we need to be taught to know that Love.

But until the kingdom comes, we are all divided. We are divided by a society that lays claim to us depending on how we look, how we identify, who we love. We are in exile by our own hand, which seeks to grasp and dominate. We are in bondage to fear and avarice and arrogance. We need teachers and pastors who are willing to give themselves over to the institution, as flawed as it may be. We need lighthouse keepers to remind us of the promises we have been given while the world around us does its best to dampen those promises out of fear or jealousy. We need those who are called to a different sort of exile, what one might call a holy irrelevance, at its very best a port in a storm calling out that Love never changes.

There’s more: in the world we’re living in, Christianity has become more colonized by greed and power than I think it ever has before. I believe in my heart that this is because it recognizes that it is losing the influence it once had. It’s still wholly privileged, but that privilege is beginning to fade. And in the fear that that loss occasions, it is clinging desperately to its power.

This was never Jesus’s intent.

We were never meant to cling to this kind of power.

Those of us who are called to priesthood are called to be tradition-keepers, scholars, storytellers. We are called to always be interpreting the world through the lens of that history, and indeed speaking the needs of the world back into the church. We have to live into the diaconal role we once inhabited that still dwells within us. We cannot be silo’ed off from the world.

This is what I feel most called to do. I have never seen myself as a parish priest, which is probably why the road was so long to get to that moment where the hands came down.

I’m not sure exactly how to end this long series of strange thoughts.

Perhaps in the end, there is no real end at all.

I am only one small light in a long torch-lit hall toward the banquet.

Jesus said, ‘I still have many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now. When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth; for he will not speak on his own, but will speak whatever he hears, and he will declare to you the things that are to come. He will glorify me, because he will take what is mine and declare it to you. All that the Father has is mine. For this reason I said that he will take what is mine and declare it to you.’

John 16:12-15

You ever stop and think that God might be a little queer?

I’ll quickly note that I know it’s not the most comfortable term for everyone. It’s not got a fantastic history. But I prefer it for myself as a bi person, and it’s inclusive of so much and easier to say than the alphabet soup string of letters that often gets used instead.

I think God’s a little queer.

Me & Sister Petunia at St. Paul’s Pride Day High Tea, 2017

God’s love is just so expansive and intimate and over the top. It can’t be easily defined. It’s for everything and everyone. God loves you parentally, platonically, romantically, relationally, and in a million other ways. God is like a parent, nurturing and guiding us, teaching us to walk and to love. God is like a friend who knows and cares for us so deeply in all of our individuality. God is like a lover who yearns for us, always seeking deeper intimacy out of sheer desire and delight. God is like a sibling who has walked among us and knows our struggles.

There’s no nailing down what kind of love this is. It’s so much bigger than biology, so much bigger than a house with a picket fence and the Cleavers and a dog, so much bigger than all of the other family units that have existed alongside and outside that one. It can’t be contained and the traditional models may be helpful but are not sufficient for its full understanding and expression.

God’s a little queer!

A confession: I used that metaphor to prime the pump. We’re going out a little further, because our beloved is even bigger than that.

I think God’s a little transgender!

We’ve been gifted a beautiful new framework in the world we’re living in today to explore that most complicated of remembrances: Trinity Sunday. We tie ourselves up in so many knots over what it could possibly mean to worship a God who is three but also one. At the ordinations yesterday, Archbishop Melissa told us that Augustine once said that to not believe in the Trinity is to lose one’s soul…but to contemplate it is to lose one’s mind!

I’ve preached on today’s passages before, and I decided to go back and see what I said last time, and man, I don’t think even I know now what I was trying to communicate then.

But in the last couple of years I have been so deeply blessed to receive a vocabulary, a deeper understanding, of something I have been struggling to express my whole life.

What if you’re not pink OR blue? What if you’re kind of violet? What if you’re something else entirely? What if you’re handed this binary system of female and male as a little kid, and it just snaps in your hands and you panic, and you spend more than half of your life thinking, “Ohhh I can’t believe I broke it!†and then all of sudden, you realize it was a questionable system from the get-go and in fact it wasn’t God that handed it to you because God was busy doing other stuff like making beautiful sea creatures that don’t even have a biological sex much less a gender?

And then, suddenly, you come to church on Trinity Sunday and you realize, “Wait – one God in three persons, undivided…that sounds a little trans, a little nonbinary,†and then you think, “God is so cool,†and THEN and then you think, “The church is so cool for figuring this out like 1500 years ago!â€

This may sound fanciful, but it’s actually on the forefront of queer theology to reconsider our God in these terms. And it’s not as if there wasn’t some pretty fanciful stuff happening all throughout the church from the very beginning.

God, a being outside of gender who is described with archetypal images of both genders (warrior king, mother hen), and who ultimately chooses a gendered expression to reach us more closely. Jesus, transcending straight-forward male presentation with countercultural actions like footwashing and a divinity within. The Holy Spirit, so trans she eschews a body altogether only to rest upon us at times, indwelling our bodies when she is invited.

And throughout the history of the church, there were many theologies and images outside the binary system we’ve idolized in these later years. The ancient Greeks of St. Paul’s time believed that your physical behaviour could actually affect your biological sex! And for years theologians and mystics, no matter their gender, referred to and understood all human souls as female. St. John of the Cross, a Spanish contemporary of Teresa of Avila, describes his own soul this way in his masterwork “The Dark Night of the Soul†– and if you think, “Well, the soul is never explicitly named as female in that poem,†you’ve got to come to grips with the fact that the alternative is that John’s male soul was sneaking off to a romantic tryst with a male Christ!

No matter which way you slice it, God’s a little queer!

You’ve got to think that God must be at least as diverse as we are.

Imagine how we’ll be imagining God in a few more decades. “I still have many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now.â€

Now of course the church is made up of a patchwork quilt of people of all colours, creeds, nations, genders, and orientations. I suppose you could just as easily say the church herself is a little trans! But a Trinitarian God is not merely a God who presents differently. Gender and orientation is just one piece of who we are as people and as Christians.

No, a Trinitarian God also acts differently than we might expect.

A standard assumption about a divine being might be certain characteristics like remoteness, timelessness, omnipotence, omniscience.

A Trinity is, by its nature, invitatory. It is always in the process of inviting.

Here in the West, we often get caught up in the confusing whirlpool of “being†and “substance.†We ask ourselves what it means to be three-in-one and one-in-three. But in the Eastern Orthodox traditions, there is more of a focus on a sort of movement, on action. The Greek word perichoresis is used to describe a sort of dance that occurs between each person of the Trinity. If you think of three people holding hands and dancing in a circle, you will see each one has its distinctions, but joined together they are also one thing, a new thing, woven together.

I think in the world we’re living in today, this is a more helpful way to contemplate the Trinity, a way that has so much to teach us in a comparatively lonely city and a comparatively lonely time.

You can see this reflected in Scripture as we heard the beautiful words of Proverbs, describing to us Lady Wisdom calling in the streets for all to join her. She’s not going up to individuals and inviting them personally. Her invitation is total and unrestrained. She doesn’t care who comes to eat with her! Doesn’t matter if you brought your tux. Doesn’t matter if your plus one is same or opposite gender. Doesn’t matter how old you are or if you expected to be invited to dinner tonight. You’re welcome, if you heed the call.

And indeed this is simply another outpouring of her delight at the beginning of creation, laughing to watch the cosmos being spun, beside God like a master-worker.

From the beginning, from first light to the cross to the brand new light of today and ever after, this Triune God unfolds a tapestry of every colour to adorn the whole earth, and the only intent in doing so is to invite all creation to take part in the dance.

Beloved, the Spirit of truth is here, and calls us at the gates – calls us to keep her way of open arms, unfettered hospitality, and bold delight.

You will know her by her fruits: joy, peace, love, compassion, and hope.

Take a basket, and share them out.

This is my first series of posts on my ordination journey. It is likely not the only time I will write on my story of faith or the journey I made toward becoming a priest. These were preliminary thoughts.

PART I: FOR THE MUSIC

My hands wound themselves together into a wild bird’s nest of uncertainty.

Dean Peter Elliott, my priest, waited patiently.

Finally I said, with a giggle, “You can tear up that paper I gave you last time. The one with the five year plan on it?â€

“Oh?â€

“Yeah. I’m not sure what to do now.â€

Somewhere in the forests of trinkets from my childhood is a photocopied and stapled sheaf of papers. This is the “yearbook†that my sixth grade teacher put together for our class. Neat rows of black and white photographs line the pages, with short blurbs beside them.

My picture is…not great. I had protested that I hated photos of myself, and when I was asked why I said, “I smile weird.†Whoever took the photo then said, “What do you mean? What does it look like?†I widened my eyes and twisted my lips into a clownish close-lipped smile…and heard a sneaky click.

The blurb next to the photo says I want to be a poet.

Fast forward twenty years and you’ll find another photo on my Facebook page.

Fast forward twenty years and you’ll find another photo on my Facebook page.

In this one, you can’t see my face. The white sleeve of an alb is in the way. Archbishop Melissa Skelton, the first female bishop of the Diocese of New Westminster, has her hands on my head.

Behind me is a sea of clergy in white, with their hands on my shoulders or on the shoulders of the people in front of them.

Whatever strange molecules work the magic of ordination must travel like electricity.

There had never been any indication that my life would turn out this way.

My earliest memories are mostly related to church and music.

Whenever someone asked Mum about her faith, she would mutter, “Oh, I just go to church for the music.†And through the ‘80s and ‘90s that was mostly true, although as I began to learn more about my family history I started to question those long-ago denials. Great-grandpa was a missionary and abolitionist. My grandfather was a church organist for ten years. The importance of faith ran deep in my family. Mum’s demurrals ring hollow even now – she could have signed up to sing with a secular choir like Phoenix or Electra. But no, it was always choirs that focused on sacred music, because that’s what she loved. It’s what spoke to her.

I would watch Mum sit back in her chair as she listened to Chanticleer or The Tallis Scholars and close her eyes, letting it wash over her. I remember thinking, “This must be very profound.†And so I too would listen, absorbing Renaissance polyphony and simple plainsong and the intricate Celtic knotwork of English choral Matins and Evensong tones. Mum would take me to rehearsals for different groups with a bag of toys and books and leave me in a corner to myself. I crafted complicated narratives with plastic ponies and dinosaurs, all the while subconsciously breathing in the glory of Palestrina, Byrd, Vaughn Williams, Bach, Handel, Gabrieli, Willan. At that time, Christ Church Cathedral had no children’s programing, and so there was nothing holding me back from soaking up the sacred fumes all around me.

When we moved to Ottawa when I was eight, we joined St. Matthew’s Church in the Glebe, which had a brand new Women and Girls’ choir. The Men and Boys’ choir was a long-established tradition here where Anglicanism was more entrenched than on the secular west coast. This was a place where, when I told church people my godfather was Patrick Wedd, they would gasp in admiration.

I entered into a strange new world of blue and purple robes, white neck ruffles and surplices, and silver “Head Chorister†pendants; a world of Responses and Psalm pointing; a world of passing notes and braiding the long multi-coloured streamers attached to hymnal bookmarks during the sermon; a world of my mum cranking the volume on Handel’s Messiah in the car so we could sing along as we drove to Montreal most weekends, where Mum would sing in my Uncle Paddy’s choir, Musica Orbium Acceuil.

When we weren’t at St. Matthew’s or in Montreal, my mum brought me to St. Barnabas, an in-the-rafters high Anglo-Catholic church. In my memory the smell of incense is perpetual and the lights are always low. They did not have a children’s choir, and so there I was allowed to let the music cover me like a blanket.

Music was an easy conduit to the divine. There was never a struggle in my search for profundity. It was easily accessible.

Jesus was friendly, and God was vast. And that seemed okay.

This homily was preached at St. Mary’s Senior’s Eucharist, which occurs semi-quarterly. Residents of the care home where I serve as chaplain are always welcomed by the St. Mary’s community along with residents of other care homes and shut-ins, and included in the service and the wonderful tea served afterward.

When the day of Pentecost had come, they were all together in one place. 2And suddenly from heaven there came a sound like the rush of a violent wind, and it filled the entire house where they were sitting. 3Divided tongues, as of fire, appeared among them, and a tongue rested on each of them. 4All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other languages, as the Spirit gave them ability.

5 Now there were devout Jews from every nation under heaven living in Jerusalem. 6And at this sound the crowd gathered and was bewildered, because each one heard them speaking in the native language of each. 7Amazed and astonished, they asked, ‘Are not all these who are speaking Galileans? 8And how is it that we hear, each of us, in our own native language? 9Parthians, Medes, Elamites, and residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, 10Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya belonging to Cyrene, and visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes, 11Cretans and Arabs—in our own languages we hear them speaking about God’s deeds of power.’ 12All were amazed and perplexed, saying to one another, ‘What does this mean?’

Acts 2:1-12

Two years ago, I had the great privilege of traveling to the Holy Land with a group of students and clergy in their first five years of ordained ministry. We stayed at St. George’s College, the Anglican Cathedral in East Jerusalem. Our group was diverse – a third of us carefully selected from the global South: English, Americans, Canadians, Sri Lankans, Africans, New Zealanders, Australians, and Filipinos. The staff of the college was similarly diverse.

Every day, we and several staff members at the small college would gather for Morning and Evening prayer, and often we would gather in the small stone chapel. One evening, however, we gathered in the Cathedral itself, a beautiful old-fashioned Gothic building with great acoustics, dark wood paneling, and a lot of stone and marble.

As we gathered, my friend Ernest stood before us to teach us a Tanzanian song from his homeland. I still remember how it goes:

Hakuna mungu kama wewe

Hakuna mungu kama we

Hakuna mungu kama wewe

Hakuna na hatakuwepo

It means, “There’s no one, no one like Jesus / There’s no one, no one like him.â€

Susan, the associate dean of the college, had officiated that night, and was dressed in full black cassock. She had spent three years living alongside these three, and remembered the song well. All three of them started to dance as we sang, big smiles on their faces.

I remember thinking, as I stood in this English style church in the Middle East, watched this white American dancing with black Tanzanians, and sang a Swahili song alongside folks from nine different countries, that this was the best of the Anglican experience, and indeed the best of the church. No matter who or where we were, we could come together to worship.

And indeed, this is the true experience of Pentecost.

The Holy Spirit is about the business of blowing down doors, making fuel of our old assumptions, and setting our hearts ablaze. She is about drawing us in, no matter our colour, no matter our language, no matter our gender, no matter our orientation or ability – she wants us to be a part of the world God is creating.

Where Jesus gathered his disciples together in one small room and gifted them the Holy Spirit, telling them to love one another, the Holy Spirit blew open the doors to spread out across the world, far and wide, letting nothing stand in her way.

So too have we been drawn together today, from so many languages, peoples, and nations, to praise the one who breaks the darkness with a liberating light.

So too are we called to go out into the world, crowned with fire, witnessing to the beauty, joy, and love we see springing up all around us.

It is a simple thing – but it is the most important thing.