Archive for December, 2018

“Stooping to Bethlehem,” (Sermon, December 23th 2018)

“But you, O Bethlehem of Ephrathah, who are one of the little clans of Judah, from you shall come forth for me one who is to rule in Israel, whose origin is from of old, from ancient days.â€

In January of 2017, students of the Jerusalem Ministry Formation course piled into our big bus and trundled down Salah-al-Din drive in East Jerusalem. We were to begin the day at Yad Vashem, the Holocaust museum, and then head south to the city of Bethlehem.

At Yad Vashem, there is a monument called the Children’s Memorial, a black box structure with many interlocking corridors hung with tall panes of mirrored glass. Throughout the building are tiny electric lights, which, when multiplied by the mirrors, give you the feeling of standing in a black sea of fireflies. The photographs of children who were murdered in the Holocaust are projected throughout, and their names read aloud.

It’s incredibly powerful, a bit devastating.

As I remember standing there, I wonder again how many King Herods we will allow as a species.

Afterward, we drove south into the hills. Modern Bethlehem, like its ancient counterpart, is occupied territory. The border wall splits the city in two and, more recently, curves around, making travel difficult, and preventing access to the tomb of Rachel to Christians and Muslims.

Honestly, Bethlehem probably hasn’t changed that much since the days of Jesus. It’s not a big town, and like many Palestinian towns it’s dirty and dusty, with a lot of crumbling infrastructure and terraced hills marked with scrub bushes.

We gathered in Manger Square. A gigantic Christmas tree, almost perfectly cone-shaped and bedecked with gold baubles and a dull grey star strung with lights, stood between the local mosque and the Church of the Nativity. This church, one of the oldest continuously used Christian churches in the world, was under construction when I was there, much of the inside hung with tarps and cluttered with scaffolding as people worked to preserve old frescoes and fix water damage.

I guess incarnation is always a work in progress.

The church itself is a rather charming mishmash of traditions. Each sacred space in the Holy Land is curated by a particular denomination, and the church of the Nativity is in the care of the Greek Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic churches. They have separate areas in which they worship, and all of the glory of the Orthodox tradition is everywhere – spectacular wrought iron, magnificent icons, gold and silver and silk, those distinctive, incredibly intricate silver and gold hanging oil lamps, fresh flowers and lace.

We were led toward what folks call “the grotto,†which is a tiny sunken chapel that, according to tradition, contains the site of the birthplace of Christ. It’s pretty clear to most archaeologists and biblical scholars that this is probably not actually the site, but such is the way of the Holy Land, a place so full of mystery and contention that each holy place, no matter its actual significance, becomes spiritually charged with the faith of the believers. I found that what continually inspired me most on that trip was the devotion of others. Human beings truly are stronger, in all things and all ways, together.

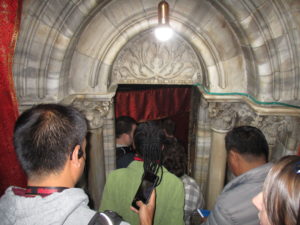

To access the grotto, you have to get in line. There are a lot of lines in the Holy Land, but thankfully in Orthodox churches, there are lots of things to look at while you wait. Beautiful gilt processional crosses and circles. Stunning icons in glass boxes adorned with strings of pearls and glass beads – offerings from the faithful. A poor box with a picture of Jesus and his name written in Greek and Arabic. And finally, the structure placed over top of the grotto itself, a marble archway with exquisite carvings, and a passageway with stairs leading down, its walls festooned with red silk embroidered with gold – for me, pretty suggestive considering I was descending to stand in the supposed echo chamber of the womb that carried the Source of all life.

Our prof, an affable Australian, chuckled and said he didn’t think it was intentional. I’m not so sure.

We entered the grotto and I found myself in a sizeable crowd. Icons and hanging lamps are everywhere. Two young Muslim women in hijab stood by the birthplace to pay their respects. Jesus and Mary are holy figures in Islam too. I felt privileged to have them there with us.

The supposed birthplace is marked by a silver star laid into the marble, and an altar is placed over top, with a space for the faithful to kneel and get close to it. The crawlspace itself is also festooned with icons and lamps, like the tiniest church you’ve ever seen. Nearby, behind a bronzed frame sculpted with images of wheat, is another little cubbyhole in which a crib has been laid: the supposed place of the manger.

You’re often warned when you go to the Holy Land that the things you expect to move you may not, and things which you don’t expect to move you may. The Church of the Nativity was definitely the former. Unlike many of the people I was with, I don’t feel particularly turned off by ornate churches, but this one left me feeling pretty empty.

What caught me up in Bethlehem was our trip to the wall outside Rachel’s tomb. Rachel, a holy figure for all three monotheistic faiths, used to be accessible to all, but now can only be accessed by her Jewish children. Standing before the wall, which is covered with gorgeous protest art in many languages, we were instructed not to get too close, because the wall had jets which could spray us with tear gas if we annoyed the guards in the tower above.

Most of us became tearful as one of the students read the story of Rachel’s death, which like Jesus’ birth occurred on a byway. Rachel dies giving birth to her last child, whom she names Ben-Oni, “son of my sorrow.†Despite her status as particularly beloved wife of Jacob, he refuses to honour the name she gives her son, changing it to Benjamin. In pain or denial, it doesn’t matter. The full truth of Rachel’s story is erased for a more convenient narrative.

And yet, as I stood there brimming with anger and sadness, my new friend Billy, a gentle gay man from New York, began to sing softly, “Let there be peace on earth, and let it begin with me.â€

Mary, unencumbered as of yet by this wall, travels to visit cousin Elizabeth, whose story is in some ways far more miraculous than hers, for what would startle you more: the pregnancy of a teenaged virgin, or a post-menopausal octogenarian? Elizabeth speaks this beautiful prophecy:

“Blessed is she who believed that there would be a fulfillment of what was spoken to her by her Lord!â€

Blessed is she who believed.

Standing in the walled up places of our lives, the occupied places, the disputed places, it seems impossible to believe in the truth of Advent, the truth of the coming incarnation, the truth of the fulfillment of all things. Standing before walls set with gas jets and soldiers with guns and fences with barbed wire and hearts bricked in for fear and protection, who among us can believe in the hope, peace, joy, and love we are promised?

Standing in the walled up places of our lives, the occupied places, the disputed places, it seems impossible to believe in the truth of Advent, the truth of the coming incarnation, the truth of the fulfillment of all things. Standing before walls set with gas jets and soldiers with guns and fences with barbed wire and hearts bricked in for fear and protection, who among us can believe in the hope, peace, joy, and love we are promised?

Few of us are called to be so steadfast as Mary, and so foolishly hopeful as Elizabeth. But maybe we can come to this by steps. And indeed, maybe that’s what Advent is about in the first place. In the Godly Play Sunday School curriculum, Christmas and Easter are referred to as “great mysteries†that the Christian needs time to enter, which is what Advent and Lent are for – getting ready.

The silver star in the Church of the Nativity, set into the marble, is not in the middle of the church for hundreds to cluster around. It’s in a grotto, into which you must descend.

Likewise God did not choose an empress or even a princess of Jerusalem in which to be enfleshed.

God chose Mary, in dusty contentious little Bethlehem, and her cousin, old Elizabeth, to bear the one who would announce the coming of Mary’s son.

And if of such humble matter God can make monarchs, how much more can God raise us up?

If you are ready, come tomorrow, and see what Love has done.

The Green Robe (Letters from the Coast)

This photograph, to me, has always held the scent, the sight, the feel of Christmas. It’s a photo of my maternal grandmother, Gwendoline Hind-Smith, wearing a green robe with gold butterflies.

This photograph, to me, has always held the scent, the sight, the feel of Christmas. It’s a photo of my maternal grandmother, Gwendoline Hind-Smith, wearing a green robe with gold butterflies.

I don’t remember the story of the robe, but I know it was her favourite for years. The picture was taken in Philadelphia, where my uncle and aunt lived for several years with their daughters, at Christmastime. Granny had decided to come with us that year. She had broken both ankles slipping on an icy driveway not long before, an event I vaguely remember in clear but disjointed images, like a poorly edited filmstrip – looking over my shoulder to see Granny, supported on both sides by two male relatives and her feet dancing briefly before she went down; back inside, one ankle bleeding slightly and the other black and blue under the soft lamplight; later, two booties fastened with Velcro and propped up on a footstool at Uncle Patrick’s house…

And, of course, the green robe.

I always thought my grandmother terribly glamorous, and indeed that was an image she cultivated her whole life. She was born in 1917 and grew up one of five Irish sisters (as the family history goes). She always wanted a life of excitement and glitz, which was what brought her to Italy to study opera. The stories differ, but somehow she wrecked her voice – perhaps with a bad teacher, perhaps with the countless cigarettes she smoked, with the truth probably being somewhere in between (although my money’s still on the cigarettes).

This, of course, was in the ‘30s or ‘40s, so…you can imagine how that turned out. She ended up in the Women’s Auxiliary as a Junior Lieutenant and met my grandfather (fifteen years her senior and already married with children, but that’s a whole other story). They eventually settled down when the war was over, and my grandmother entered into the ‘50s as a mother of three – not an opera singer.

Memories of her are not as fresh as they once were, but are still tinged with a deep intimacy. She cared for me while my mum was working not long after my parents separated, and I still remember afternoons of drawing on her big easel, rummaging through her costume jewelry, and pretending to be “Mrs. Cat†coming to tea. I remember being called “baby lamb,†fed digestive biscuits, and naps in the odd dark space in back of her apartment behind the enclosed kitchen, with the ticking sound of an old fan a constant companion in the summer.

Her death, which was from lung cancer, was not unexpected, but it was still nearly impossible to fully absorb. My clearest memory is of understanding that she was not coming back, not ever, and how terrible and lonely that was. I think that that memory, that sense of loss and confusion at the impermanence of one so beloved, has done much to shape who I am today.

And yet, slipping this photo out from a pile of others at my mother’s dining room table one rainy November evening of this year, I felt an almost palpable surge of longing and love. It was almost like looking back across time and tasting, once again, that gigantic feeling that always accompanied the arrival of Christmas when I was a young child, that sense that magic was real and all around us, and perhaps that the gathered family, whatever its composition, was itself the conduit for such things.

I often tell people that I believe that elders, particularly those who suffer from dementia, do not so much lose their sense of time and memory as they begin to travel between worlds and across time. Perhaps first it occurs involuntarily, and then in death perhaps they voluntarily step out of the bodies that can no longer sustain them and take on a brand new unknowable form.

Contemplating the beauty of that remembrance of childhood wonder, I can’t help but think that this experience is rather like that, that I have been helped across the threshold for only a brief moment in time and find myself standing in my old/young child’s body, full of a child’s electricity and openness, but with all of the gratitude only an adult heart can feel.

What a gift.

Resistance Lectionary Part 25: Hope Abides

Today’s Citation: Isaiah 6:1-10

This is another passage that is very popular at ordinations, but tends to be cut off early. No-one likes to hear verse 9 and those following! What could they possibly mean? What kind of folks want to hear that their new cleric is bound to speak truth that they will refuse to hear? And who in the world wants to hear that God’s desire is for us not to be saved?

Churches shouldn’t feel too defensive or indeed get too down on themselves when they hear this. People in general would prefer not to hear anything that challenges their deeply guarded sense of self. There is no shame in that – unpleasant truths are unpleasant for a reason. We can so often find ourselves shaken by the realization that we are not perfect…and indeed sometimes we are far, far less than perfect.

But we are called to grow beyond flawed self-images and easy defensiveness, as painful as the growth may be. And in the world we’re living in, where the stakes are getting higher every day, maybe we should sit down and consider whether or not we have allowed our greed and excess to haul us past a point of no return.

What if it is too late to be saved, as we sit here squabbling in a little bubble as the world burns around us and polar bears drown and millions starve while the happy few in the West hoard food even as it spoils?

The gift of Isaiah is that it’s a terribly long book which many scholars believe is actually a collection of three books, possibly written by three different people or groups of people. The first, as we see in this passage, is not very hopeful, and most scholars believe that this Isaiah might have been the OG Isaiah, who was watching the state around him beginning to crumble as it attempted to assert itself and fell victim to corruption and pride. Eventually, of course, the state fell apart and was partitioned off to the ravenous nations that brought about its downfall. This is likely the background for Second or Deutero-Isaiah, written during the Exile, which promises restoration and the coming of a Messiah who will liberate the Jewish people from the Persians (here referred to in code as “Babylonâ€).

Throughout all the woes and fears of the coming apocalypse, however, is a glimmering thread of hope that God will call back a repentant people into the arms of love.

This is the hope given to us as Christians: that Jesus was sent to us because God cared so much for our salvation that, recognizing we were having trouble obeying Her words on a page, brought us a human figure with whom to identify.

And not a powerful or scholarly or superhero figure.

A poor, likely illiterate brown man, who gathered all people to himself, healing and proclaiming good news.

The joy of Advent is that we are looking forward to the eventual return of Jesus, as well as the revelation of the incarnation at Christmastime, the ecstatic wonder of God taking on our flesh in order to close the gap between fragile mortality and the infinite. And while the response of the empire to his message was arrest and execution, it was not enough to halt the light.

There is always hope, even at the end of the world.

Magic Hour (Letters from the Coast)

Last week, I woke up early for some reason, and was privileged to witness a quietly exquisite thing: though it was 7.45am, the sun had only barely risen. A light coating of frost dusted each rooftop like icing sugar, and the place where the sky lay across the mountains had been painted light pink shading gently into violet and blue. From inside our apartment, everything seemed terribly quiet apart from a few crows or a gull in the distance.

Even the cat seemed to share in my awe. She stood at the sliding glass door of the balcony with one paw slightly raised to be let out, but when I opened the door she just stood there, staring, and so did I.

It’s not terribly unusual for the sun to be up so late only a week from the solstice, but as I rarely get up this early anymore, it’s not common for me to experience these hushed pastel hours. I refrained from turning on the lights for some time, opting instead for this computer screen and the seasonal LED strings I put up around the fireplace at this time of year.

Morning Prayer followed, and it only took ten minutes or so for the sky to begin to lighten further, to shade from pink to gold and to bring with it the more ordinary colours and sounds of the day, and a muted feeling of loss passes across my heart like a shadow.

There’s a reason the directors call it “magic hour,†that moment of perfect balance between night and day. Dawn. Dusk. Twilight – literally, “in-between light†– for some represents the sacred. Rabbi Elliot Rose Kukla writes,

“We might have thought that the ambiguity of twilight would have made it dangerous or forbidden within Jewish tradition, since twilight marks the end of one day and the start of the next. But, in fact, our Sages determined that dawn and dusk, the in-between moments, are the best times for prayer… Jewish tradition acknowledges that some parts of God’s Creation defy categories and that these liminal people, places, and things are often the sites of the most intense holiness.â€[1]

(By the way, if you were wondering why my first piece for “Letters from the Coast†was called “Dusk Child,†this is why).

As I contemplated this, I opened my email and saw I had been invited to a celebration of Şeb-i Arus by my Sufi friends. Şeb-i Arus, or “the wedding night,†is the name for the anniversary of the death of Rumi on December 17th, where the Mevlevi order of whirling dervishes celebrates the final union of Rumi and his beloved, the divine.

And how appropriate that it is celebrated only scant days before Christians around the world (at least those who follow the Gregorian calendar) celebrate the union of heaven and earth with the incarnation of Jesus Christ into the world.

In both of these celebrations, I mused, ascent and descent are merged into a sort of strange dance. Rumi, lover and poet, at once ascends to his Beloved, while his body descends to the earth in death. Christ, the one who comes among us, having overshadowed Mary by the work of the Holy Spirit (in a sense, descending to be made incarnate in the womb of the God-bearer, the Theotokos), also ascends from Mary’s womb, passing from holy darkness to thoroughly mortal darkness…and, eventually, the thoroughly mortal light of his first dawn and indeed his eventual resurrection.

Twilight is so much more than a time on a clock (or a set of questionable novels, heh). It represents a moment in which all things are held in balance, truly a Kingdom moment of unity, made all the more precious for its evanescence.

God in God’s grace has given us a taste of total balance, a model which, if we are willing, can colour our whole lives with its expectancy, its gentle pastels of longing.

——————————–

[1] Rabbi Elliot Rose Kukla, “Created beings of our own,†in Righteous Indignation: A Jewish Call for Justice, ed. Rabbi Or. N. Rose, Jo Ellen Green Kaiser, and Margie Klein (Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2008), 219

Resistance Lectionary Part 24: Prophets of Power

Today’s Citation: Jeremiah 1:1-12

The season of Advent is a season of prophecy and anticipation, a season where we are called to look ahead to a new cosmos of justice, blessing, and unity. Here, we are welcomed into the story of Jeremiah, a prophet who suffered greatly for his brave actions in the royal court.

Prophets are plentiful in the Bible, but there are many differences between them. Elijah, Elisha, and Amos made their proclamations mainly among the poor, only occasionally having words with the royal class (and almost invariably bad ones), while Ezekiel and Jeremiah were of a higher class, and mixed with royal circles in the courts of the palaces.

This, however, did not determine favour or safety, and Jeremiah in particular found himself at the bottom of a well after uttering a prophecy that the king did not want to hear. Their loyalty was always first to be to God, king of kings, and this was not always the ideal in terms of networking or building bridges for your career!

In these opening lines, Jeremiah first receives his call from God. This passage is especially popular at ordinations, but the focus for us today is on Jeremiah’s “Moses moment,†the moment when he cries that he is only a boy. Moments like this are common in prophetic texts, but what’s important to our purposes is God’s response, which is full acceptance of the prophet as he is.

It’s unlikely that Jeremiah was literally only a child when he first received this commission, but it should be noted that God does not respond by denying Jeremiah’s assertion. God instead tells him not to say it – again, not because it isn’t true, but specifically because Jeremiah is being called to great work that only he can do. He is not only a boy, but a hero for the people and a warrior for God.

No child is only a child. We are so much more than the designations we are given by the state or society or our peers. We are signs in the world of something greater than ourselves, but only we can choose what the something greater will be. It is easier by far to be a sign of the system functioning as it should, either by wielding our power like a hammer or accepting our lowliness as inevitable and intractable.  It is more difficult, but far more sacred, to be a sign of God’s power over all things, a sign of God’s call to the universe to break free from patterns of death and embrace patterns of life and new birth.