Jul 30 | David takes, Jesus gives: Summer 2018 Preaching Series, Part 7

Today’s citations:

Once again we return to our preaching series on kings and monarchs, and the kind of monarch we might imagine God or Jesus to be. So far, as we tend to do here, we’ve used the lenses of Scripture to explore the popular cultural understanding of what it means to be a king.

Today, listening to the story of David and Bathsheba, you may feel that the opposite is happening, and that our culture challenges the Scripture story.

It doesn’t sound the same in the era of #MeToo, does it?

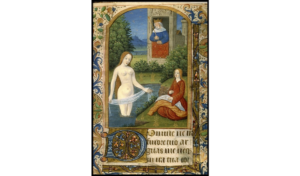

For many years scholars interpreted the story of David and Bathsheba as one of those classic “powerful guy gets screwed over by wily temptress.†This is certainly how many famous artists have depicted it, on canvas and on film. Bathsheba looks coy; bats her eyes; tosses her hair. She is the schemer who wants to get in good with the king, brazenly bathing on the roof where she knew he would see her, and then getting pregnant to trap him.

This is unfortunate, because the real story is actually a pretty radical story for a pre-feminist culture, and a scathingly self-critical one.

There are lots of clues. First off, there’s no throwaway lines in a Bible story. We should pay attention when we hear that ‘in the spring of the year, when kings go out to battle, David stayed at home.’ Things have changed for David. No longer fighting his own battles, he now sends his prize general Joab. Not inherently a bad thing, but the stories that precede today’s show us that David has stepped back from his rough-and-tumble roots and is beginning to engage in the more subtle art of statecraft with the monarchs of other nations.

Are the writers of this epic getting in a subtle dig at politicians and their ‘losing touch’ with the people? Possibly. They could also be showing us that the nation of Israel has grown from a people into an idea, something more abstract than a group of tribes.

And perhaps this is where the road to objectification leads.

So David is somewhere he should not be – not just home from battle but walking along his roof deck in the evening, and he sees a woman bathing.

Cultural note: Like short skirts and saucy banter, bathing on the roof is not an invitation. Everyone bathed on the roof in the evening in ancient Palestine. It was cooler then, and less busy. You do it on the roof because you can’t be seen up there, or at least not by the average person walking down the street. The only people who would be able to look down on you literally would be the ones who could do so figuratively, because they were rich and lived in a house that was higher than yours.

Here we see carefully laid bricks of meaning and metaphor. Bathsheba is not in control here. This story is about David’s abuse of his power.

So King David the peeping tom likes what he sees, and he asks about her. His servants tell him she’s a married woman. David knew Uriah, if not personally than peripherally, but that doesn’t stop him. He sends for her, and she goes.

Did the servants tell her why David wanted to see her? The text doesn’t say. It gives no indication that she even wants to go, but the king has sent for her so she goes, because that’s what you do.

Now if this story occurred in the #MeToo era, it would have been spun as a “he said, she said†story, because none of us know what happens in that room. However, the Bible is often quite candid about the feelings of women in its stories. And in this case, Bathsheba, like David’s nation, has become an idea – or in this case, an object – rather than a person.

We can’t honestly talk about consent when those concerned are a king and a subject, and not just a subject, but the wife of, for lack of a better word, an employee. At that point, intent doesn’t even matter. Those given power over others must be bound by higher laws than the average shmoe. A teacher and a student are not appropriate romantic partners. A doctor and a patient are not appropriate romantic partners. A king and a subject married to his employee are not appropriate romantic partners.

David should know that.

You can understand why I became annoyed at the heading assigned to this passage in my Bible: “David commits adultery with Bathsheba.â€

No. We have a better word for what really happened.

This is a betrayal of David’s God-given grace and power.

And it gets worse. Bathsheba becomes pregnant. Can you imagine how frightened she must have been? He could have had her killed. Instead, he attempts to manipulate her husband, and when Uriah turns out to be a far more honourable man than David, the king has him killed – in a cowardly, devious way.

Once Uriah is dead, poor Bathsheba, none the wiser about what really happened, laments, and then is brought into David’s house. Again, David is still in charge. And while she may have been relieved to know that she and her child would be cared for, it’s still a problematic marriage.

This touches on something that frustrates a lot of women seeking justice. There’s a lot of talk about how women have the power to ruin men’s lives by one “misunderstanding.†But this movement is about what happens when power imbalances exist and are maintained by the constellation of people around powerful folks. In some ways, Bathsheba’s story is easier to understand, because David’s power was absolute. To whom would anyone report his behaviour? David didn’t have an HR department! There weren’t newspapers that would line up for a juicy expose. No one had any recourse.

This is why God ordains prophets. As we’ll hear next week, Nathan is the one who confronts David with his sin, face-to-face. He advocates on Bathsheba’s behalf, because God never forces people to confront their own attackers.

Only our court system does that.

This is the first week where we see that David, beloved by God, is not a man subject to every temptation you’d expect. Having been given the world, he decides to take – to take his pleasure, to take someone’s autonomy, to take someone’s wife, to take someone’s life. Power does this to people; makes them hungry for more, more, more.

So once again, let’s contrast kings of earth with our king of heaven.

Where David takes, Jesus gives.

Jesus chooses not the royal palaces of Herod, but an outdoor field in Gentile territory; not rich robed officials but the ragged poor; not roast lamb but barley loaves and fish, the bread and meat of the poor.

What’s fascinating is that for a moment, the crowd fully understands who he is. They use a special Johannine phrase: “the prophet who is coming into the world,†and they try to make him king.

And Jesus fully renounces that.

He wants nothing to do with earthly power. He knows it is a dangerous thing.

Instead of seizing earthly power, which is but dust, he reminds the disciples who they really belong to. They see the veil of time torn asunder, and they’re back in Genesis, at the beginning, for pneuma, the word for wind, is the same as the word for Spirit. The pneuma blows over the face of the deep, and Jesus walks across it, and speaks not the bloodless English phrase, “It is I,†but Eigo eimi, I AM.

I AM; do not be afraid.

And before they can take him into their boat, they are brought to their destination. They cannot tame this king, and yet they can travel with him, touch him, hold him, at least for a little while.

The world is full of those who would take, and break, and gorge themselves on wealth and pleasure at the expense of others as though they were gods. Let us, like Nathan, never be afraid to speak out on behalf of those who are silenced, and like the disciples, remember who we really are: part of a web of life, a web of love, that dies and rises together, or not at all.