Archive for the 'NEWS' Category

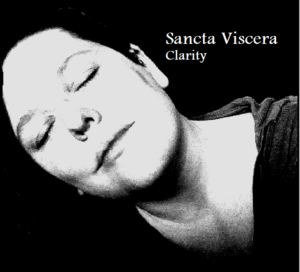

Sancta Viscera Advent Devotional Music Project

In 2016 I decided to try a totally new form of devotionals for the season of Lent: recording an album. I did so with only the tools I had at hand: my house, my instruments, my voice, my USB microphone, and my laptop.

In 2016 I decided to try a totally new form of devotionals for the season of Lent: recording an album. I did so with only the tools I had at hand: my house, my instruments, my voice, my USB microphone, and my laptop.

The result was the album The Path of Ashes, which you can listen to here.

I fell in love with the process, and decided to do the same thing for Advent of that year. By then my skills had developed (at least a little), and I produced a more polished piece called Wild Star, which you can listen to here.

I followed that project up with a second Lenten album in Lent of 2017, Pilgrim Song, which you can catch here. This time I did it with a digital drum kit, and became even more excited with the results.

I’m closing out the year with Sancta Viscera, and just released the first track today here.

I will continue to share the tracks with y’all as they come out, which they will twice a week. I invite you to make this a part of your Advent devotionals if you like. Follow along on this blog, through Twitter, or through my fan page on Facebook!

It is offered freely, to the glory of God and for the work of the church. Physical copies of the previous albums (and eventually this one) are offered by donation with 100% of proceeds going to the church where I am stationed. If you’d like a copy of any of the previous albums, please give me a shout!

The Beauty of what you Love

Last night I made my way over to the place where, once a month, a small group of faithful people gather to hold Unity Zhikr.

A zhikr is a devotional act in Islam in which short phrases or prayers are repeated silently or aloud. In Sufism, the ceremony often involves song, dance, and other liturgical elements which vary according to the lineage or order.

I had heard about Unity Zhikr through Seemi Ghazi, whom I met formally at a Clergy Day on Islam in November 2017 – hands-down the most inspiring and wonderful Clergy Day I had ever been to until then. I had come expecting a lecture, perhaps a panel discussion. What we received was one of the most beautiful and intimate encounters with Islam I could have imagined. Seemi told us the story of the birth of her daughter, a performance piece rich with Islamic symbolism and meaning, enhanced by song and sura and, at one point, the beating of a drum. After that, she taught us how to pray salaat, answered some of our questions, and invited us to participate in a sama, which is a form of zhikr practiced by Sufis.

I had been a part of a sama before at VST several years ago, and it was one of the most powerful spiritual experiences I had ever had. Seemi had been present at that sama, as well as Raqib, whom I had seen whirl once before at a UBC event. Raqib is a rather fascinating individual: an older white man with a slight, almost delicate frame, and an incredible air of peace surrounding him. He doesn’t seem to speak much, and every movement appears incredibly deliberate.

In that first sama, there had been three whirlers, who danced in the middle of two circles of people which also turned in a round dance. I was in the inner circle, our hands joined and going up and down as we chanted, “Bismillah, bismillah†(in the name of God) over and over until I was almost in a trance. My best memory of that was Seemi, who had her young son with her. She held him in her arms as she whirled, and I remember the look of utter delight on his face as she spun.

This second sama, made up almost entirely of clergy, was smaller, and we did not move. We held hands and stood where we were. I can’t remember exactly what we sang, but I think it was simply “Allah.†Raqib stood in the centre, dressed in traditional garb: a tall brown hat (called the kûlah) and a white gown (the tenure), which at first is covered with a black cloak (the hırka). All of these articles symbolize death: the hat, a tombstone, the robe, the grave, and the white gown death itself. This garb is common to the Turkish Mevlevi order, the famous whirling dervishes.

Raqib eventually shed the black cloak and began to turn as he played the drum and Seemi sang, her voice soaring over our chant. Whirlers turn on the left foot, while the right steps around it. There’s something utterly hypnotic about it. I could watch a whirler for hours. I was most intrigued by the first dance I had seen Raqib do, which he did without a drum. The whirler begins with their arms crossed over their chest, and eventually lifts them, right palm up and left palm down. This, as I understand, is a posture indicating the relationship between heaven and earth.

I felt transported after this second sama. I thought, “How can I get more of this in my life?â€

I went and thanked Raqib, who received my hands and bowed to me without saying anything. Then I spoke to Seemi, who enfolded me in her arms as I thanked her. She passed on the information about Unity Zhikr, which she had to do personally as they are cautious about being too public.

I arrived uncertain of what to expect. There were only three people there when I arrived. A space had been cleared in the middle of the room and a woman swept the floor while two older men sat outside the space in chairs.

The woman came to me and said they would start soon. We talked a little bit, and her face lit up when I told her how I had come to be there. I thought she looked familiar and suddenly remembered that I had seen her whirling at Christ Church Cathedral during an event of remembrance for those who had died in the fentanyl crisis. I had been moved by this act of prayer, and astonished that she appeared to do it for at least half an hour, probably longer.

More people began to arrive, including Raqib, and eventually someone brought in a boombox and put in a CD with flute and chant. The woman came and taught me how to whirl, explaining that they preferred to teach through action and without words.

“If you get dizzy or nauseous,†she said, “bring your head down lower than your body. Just bow, like this. It will help.â€

I was a bit nervous; I was never that kid who loved spinning until they fell. My last experience of spinning around was probably at Camp Artaban doing staff “initiation,†where I had put my forehead on the end of a baseball bat and spun until I felt like I was going to fall, and then threw it down and snapped, “I’m not doing this,†to my boss.

We bowed to each other and started slow, our arms crossed over our chests. My steps were still separate, with the right foot stepping around the left and the ball of the left never really leaving the floor. Then we raised our arms: palm up, palm down. I managed to do it longer than I thought I would, and had a cool feeling imagining myself as a tree rooted deeply in the floor, but I did eventually get dizzy and had to stop.

The woman stopped with me and we bowed deeply to one another. She gazed into my eyes with a small smile, and I did the same. It felt intimate.

She gave me a few more tips, and we started again, bowing to one another, and then beginning to turn. This time there were more people and they joined us – women and men. Raqib picked up his drum and came to walk between us as we whirled. I raised my arms and focused on my thumb: specifically, on the little white “moon†of my thumbnail.

I felt myself become lost in the music. Raqib chanted along with it, sometimes walking around me in a circle, sometimes walking in a bigger circle around the rest of us. In my peripheral vision I saw the others turning much faster and moving their arms up and down. I tried doing this once but decided quickly I was still too green: the movement of my “still point†made my feet unsteady. I did, though, manage to turn faster until I was moving almost continuously, my steps no longer separate. The music settled into my bones as everything around me disappeared except for that rising moon on my thumbnail.

I think I whirled for nearly ten continuous minutes, and not once did I fall or get nauseous or overly dizzy.

I’m still in a bit of shock that I did that.

Finally, we stopped, and a few of us came to stand in a circle, holding hands. Raqib stood to my left. His hand was warm and pleasantly leathery. We prayed briefly, Raqib mentioning an awareness of the presence of someone they knew. I later discovered that this person had been a part of the community and had recently died.

After that, we laid out a big carpet and came to sit in a circle at its edges. Some folks sat in chairs, but most of us sat on cushions on the floor. We were given songbooks, and for a little while we sang songs out of the book. Most of them were suras, passages of the Qur’an. There was no music; I had to fumble along as best I could in beautiful Eastern modes and rhythms with which I was quite unfamiliar. It was wonderful to sit next to Raqib, who had a beautiful, resonant voice. On my other side was a man who appeared to be South Asian, whose voice was light and sweet.

After these songs, there was a time for the community to share their memories of this person who had died. It was very moving. Finally, we began our zhikr, which opened with a poem read by one of the men. I’m not sure who wrote it but it sounded like something Rumi would write.

I didn’t know what to expect, and this portion of the evening ended up being just as wonderful as the whirling. The lights were dimmed, and for the next hour or so we chanted. Each chant blended into the next one, and they rose and fell like the tide, with solo voices sometimes rising overhead like Seemi’s had in the earlier sama.

I found myself captivated but also somehow at home. My body began to sway with the music and this did not feel artificial or self-conscious. I had been nursing a terrible cough all week, and so for much of the zhikr I opted to be ministered to by their voices, but at one point I finally surrendered to my body’s need to sing.

We were chanting the “La ilaha illallah†(“There is no god but Godâ€), traditionally said to be the inspiration for the sama ceremony when Rumi heard it being spoken by goldsmiths beating the gold in the marketplace and responded with joy by whirling. I let my voice join, whispering at first, then singing, allowing it to build until I was singing in the octave above everyone else, hearing the voices start to rise along with mine, thinking briefly, “Oh crap, they can all hear me†before the thought was subsumed by the sacred emptiness in me. Rarely had I felt so filled. I could have done it for hours.

Finally, the ceremony ended with another poem, and then we tidied up and had tea and snacks.

I had some good conversations with folks, most of whom at first assumed I was one of Seemi’s students. The snacks were good too!

Part of what drew me to this practice was the need to get in better contact with my physicality. For all the rhapsodic language of my sermons about incarnation, I’m really not very good at being incarnate myself! I tend to prefer to reside in my head, and adore contemplative practices as well as just sitting for hours on end. I don’t like exercise at all and often approach it the way other people go to the dentist. There is no kind of physical activity I really enjoy; only ones I dislike less than others (swimming being one of them). This tendency is one of the reasons why I like Anglicanism and its “pew acrobatics” and gestures: it reminds me that worship must be done with the whole body, not just the mind or the heart. This practice of whirling, I thought, would be another simple way to become more in tune with my body, to incorporate it into acts of worship in more explicit ways.

I can’t wait to go back. I think I’d like to connect with Seemi again to talk more about this beautiful tradition.

“I hate this parable,” (Sermon, November 19th, 2017)

‘For it is as if a man, going on a journey, summoned his slaves and entrusted his property to them; 15to one he gave five talents, to another two, to another one, to each according to his ability. Then he went away. 16The one who had received the five talents went off at once and traded with them, and made five more talents. 17In the same way, the one who had the two talents made two more talents. 18But the one who had received the one talent went off and dug a hole in the ground and hid his master’s money. 19After a long time the master of those slaves came and settled accounts with them. 20Then the one who had received the five talents came forward, bringing five more talents, saying, “Master, you handed over to me five talents; see, I have made five more talents.†21His master said to him, “Well done, good and trustworthy slave; you have been trustworthy in a few things, I will put you in charge of many things; enter into the joy of your master.†22And the one with the two talents also came forward, saying, “Master, you handed over to me two talents; see, I have made two more talents.†23His master said to him, “Well done, good and trustworthy slave; you have been trustworthy in a few things, I will put you in charge of many things; enter into the joy of your master.†24Then the one who had received the one talent also came forward, saying, “Master, I knew that you were a harsh man, reaping where you did not sow, and gathering where you did not scatter seed; 25so I was afraid, and I went and hid your talent in the ground. Here you have what is yours.†26But his master replied, “You wicked and lazy slave! You knew, did you, that I reap where I did not sow, and gather where I did not scatter? 27Then you ought to have invested my money with the bankers, and on my return I would have received what was my own with interest. 28So take the talent from him, and give it to the one with the ten talents. 29For to all those who have, more will be given, and they will have an abundance; but from those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away. 30As for this worthless slave, throw him into the outer darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.â€

Matthew 25:14-30

Good morning, St. Augustine’s.

I hate this parable.

I can count on the fingers of one hand the number of good sermons I’ve heard on this parable. Usually I hear a simplistic call to embrace our talents because they were given to us by God to be used, not hidden away.

Never mind the fact that a talent is a unit of money, not a cypher for people’s gifts.

And what kind of God casts us out when we don’t use our gifts? This implies that the only reason a person might not do so is because they are selfish. But we know that’s not true. There are a million tragic reasons why someone might not feel confident or worthy enough to share their gifts with others.

What kind of God punishes people for that?

A God who is exactly as the last slave describes: “a harsh man, reaping where he did not sow, and gathering where he did not scatter seed.â€

The master even admits to his own behaviour: “You knew, did you, that I reap where I did not sow, and gather where I did not scatter?†So when he punishes the slave, he is also punishing him for telling the truth.

When we talk about wrestling with texts, a kind of passivity is often implied. But we must actively wrestle with our sacred texts, because if we won’t, it proves that we don’t have respect for them. If we lock them up under glass like Snow White, we commit idolatry by not allowing them to be more than a pretty conversation piece. If we discard the ones we don’t like, we are no better than the proof-texting cherry pickers that we so often rail against. Both idolizing and discarding Scripture implies that it is beyond reproach. If we don’t interact with it in a more intimate, earthy way, then it is dead.

Scripture’s sort of like Jesus in that regard. What saves us must be fleshy and incarnate, because that’s what we are. And Scripture is just about the fleshiest set of books we have.

Holy texts demand honesty.

That’s why I started out with that first sentence: I hate this parable.

Now let’s wrestle.

I’ve brought a friend to help us out: Richard W. Swanson, a Lutheran pastor and author of the blog “Provoking the Gospel.â€

First thought: The English text tells us the master is going “on a long journey.†The Greek original, however, implies that he may be moving to a foreign place. It is never made clear if he is returning or not.

Second thought: Swanson values five talents at about 6.25 million dollars. Who the heck would give that much money to a slave, a piece of property? Who judges their slave to have the ability to manage that much money?

What kind of master is this?

Third thought: Nowhere in this parable does it say that the slaves were ordered to trade with the resources. Swanson argues that the third slave must be the only one who actually believes that the master will return.

We have talked for the last two or three weeks about being ready. This parable is told in the context of Jesus in Jerusalem, days away from being betrayed.

Here’s where things really get broken open, though.

The Talmud, a source of Jewish law, states that when slaves or subordinates are entrusted with finances, they are to “take no risks. Bury the cash in the ground.â€

Swanson states, “This advice recognizes the reality of the power differential between master and subordinate. [T]he third slave watches as the situation develops and knows what to expect from the first two slaves: they will play the market, they will feel rich, they will gamble with someone else’s money. Playing the market makes you look like a genius. Unless you lose.â€

If the other two lost, then that single talent could be all that was left of the master’s resources. So he follows the Talmud and buries it. It’s safe, and they can use it to rebuild if they need to.

Yet for this decision, the slave is called lazy and wicked.

Not the guy who gambles with other people’s money. Not the guy who reaps where he does not sow.

So once again, I ask, who is this master?

Is this really God?

Do we want this to be God?

Do we want this to be God today of all days, when this community is still coming to terms with the terrible shock of unexpected loss?

I don’t think we can allow this to be God anymore. Because we know that this master, in some parts of the world, is still God: a god more concerned with gate-keeping than boundary-breaking, a god who forgives abusers but ignores the abused, a god of revenge and bloodshed, a god of Empire and tyranny, a god all too often imposed upon the suffering, a false god created to prop up power.

This god is at complete odds with what we see in Scripture: the God who is all-loving and all-forgiving, the God who accepts repentance and liberates captives, the God who is ruler of the upside-down Kingdom where the disabled are prophets of grace and children are spiritual masters.

So who is the master in this parable, if he is no longer God for us?

Let’s look back at some things Jesus said in the last chapter.

“‘Beware that no one leads you astray. For many will come in my name, saying, “I am the Messiah!†and they will lead many astray.â€

Later he continues, “If anyone says to you, “Look! Here is the Messiah!†or “There he is!â€â€”do not believe it. For false messiahs and false prophets will appear and produce great signs and omens, to lead astray, if possible, even the elect.â€

Perhaps, for our purposes today, we may consider this master as a false Messiah, leading us astray. A false Messiah who punishes honesty and adherence to the law, who does not deny his own thievery, who takes from the weak and poor to reward the rich and crafty. A false Messiah who could not possibly be the same as the one described in the Gospel’s following passage, who says, “Whatsoever you do to the least of these, you do to me�

If this one is false, where is our true master in this story?

We could argue that he has more in common with the so-called wicked slave, who proclaims truth and is cast out for refusing to play the game of amassing personal wealth.

Some sermons claim this parable is about taking risks, inferring that the investor slaves risked more than the slave who buried the money. It seems to me, though, that a far greater risk is taken when we speak truth to power than when we invest a tyrant’s money for his own greater wealth and our greater subjugation.

And Christians are well accustomed to taking risks, even if we don’t realize it.

St. Augustine’s, we took a risk wrestling with Scripture, because we opened ourselves to the possibility of being changed by it.

We take a risk when we say that we “look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come,†because we stand in opposition to a death-denying culture that privileges youth and beauty over frailty and inherent worth.

We take a risk when we receive the Body and Blood of our Lord, because we proclaim that God has come among us, and wants to be taken into us even now, to be once again clothed in flesh.

In some ways, these risks are far greater risks than the ones we fear in our daily lives, and yet we take them easily.

Having taken such great risks in these walls, let’s search for more when we go forth from here. Take the risk of embracing others who are different. Take the risk of working with others to bring about the Kingdom. Take the risk of loving each other, particularly now, in a time of sorrow, when you need each other most.

And if you are afraid, come first to this table. Feast on love to do the work of love.

It’s been a year

This post was first published on Twitter on November 9th, 2017.

It’s been a year.

A year of falsehood, gaslighting, hate, apathy, white male fragility, and murder. A year of protests, loud voices, undeniably beautiful strength and rage.

And as before, we approach a season of darkness yearning for light.

A season where the religion of capitalism explodes into an orgasm of cheap electric lighting and sugar and greed and booze and desperation because it knows how prophetic the true holidays really are.

Chanukah, where Jewish people remember a miracle of never-ending oil and the stubborn resilience of light in the midst of fear and oppression.

Mawlid, where Muslims orchestrate an outpouring of charity and food to remember the birth of the prophet (PBUH), beloved and giver of their greatest gift, the Qur’an.

Yule, where Wiccans and Pagans mark the [re]birth of the light which is never extinguished, and celebrate the eternal circle of life.

And Advent, that beautiful period of quiet expectation where we not only look back to that long-ago birth, but to the fulfillment of God’s kingdom and its radical justice.

The horrors of the year are not going to come to an end. It may indeed get much worse before it gets better.

But I am not afraid. Because I have seen the glory.

I have seen the outpouring of righteous anger and holy justice. I have seen the rising up of the oppressed and the turning of so many hearts. I have seen the refusal to stand down and be polite when people are dying.

I have seen a tide of hate and misogyny and racism and perniciousness and even evil…and I have seen the Holy Spirit running wild over the earth, calling the human creature to be more…and the human creature stepping up.

Don’t think I’m being optimistic. I don’t believe in optimism. I believe in hope. And hope has teeth.

Optimism exists outside of context, without reason. Hope exists only because despair exists.

And that’s what makes it stronger.

It can take a moment to crush optimism, but hope can withstand time, terror, even death.

And that’s what I got.

Kenosis (Poem)

When God tears at your heart,

open your veins.

Let life flow out:

an immediate willful river

a craving

long unsated.

Fill your lungs

deepen the red

let the flames pour out

and the all

fall in.

“Thanksgiving,” (Sermon, October 8th 2017)

“On the way to Jerusalem Jesus was going through the region between Samaria and Galilee. 12As he entered a village, ten lepers approached him. Keeping their distance, 13they called out, saying, ‘Jesus, Master, have mercy on us!’ 14When he saw them, he said to them, ‘Go and show yourselves to the priests.’ And as they went, they were made clean. 15Then one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back, praising God with a loud voice. 16He prostrated himself at Jesus’ feet and thanked him. And he was a Samaritan. 17Then Jesus asked, ‘Were not ten made clean? But the other nine, where are they? 18Was none of them found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?’ 19Then he said to him, ‘Get up and go on your way; your faith has made you well.”

Luke 17: 11-19

There he went again, running his mouth at the table, the relative who always had to have the last word, always had to be louder than anyone else, always had to prove his point. And oh did I want to slay him with my wit, but it was a bit dull, having been bathed in a couple glasses of wine, one of which was in my hand. So I bit my tongue, and set that glass down on the table…and everyone jumped as the foot of the glass just exploded beneath it.

I guess I “set it down†a little more enthusiastically than usual! I guess biting your tongue is no guarantee that your opinion of a person won’t be known.

That was Thanksgiving dinner several years ago. We’ve all experienced something like that, right? I know there’s got to have been one awkward Thanksgiving dinner for each one of us in this church right now. I’m lucky enough that none of mine have been actively painful or toxic. But all of us have experienced the awkward. Awkward conversations, awkward kitchen mishaps, awkward political situations in the world that guarantee someone’s going to get into a screaming match, awkward subtext left unspoken, you know how it is.

And yet we do it, and all too often still feel thankful. Many folks, with families or friends, will still fold themselves into the chaos and occasional sharp edges of being gathered together. There is something profound about gathering together in a world that often appears far more violent than gentle, far more cruel than kind, to eat – to aggressively celebrate our status as living creatures who love each other.

Thankfulness is not a simple emotion. Like hope and joy, thankfulness has a shadow. It is painted with shades of awe. At its most pure, thankfulness reminds us of how vulnerable we are. Maybe that’s why harvest celebrations feature it so prominently. We are bringing in the sheaves and rejoicing in the feast because we know that lean times are coming. We bask in the love we have for one another because we know that that will have to be our light for the next few months as the nights draw in and winter comes. I was made most aware of this as I wrote this particular passage Friday night and heard the rain pounding on my windows and tolling ghostly bells in my flue.

The gift of our faith is that vulnerability is a sign of blessing. This is a precious and radical thing that we give to the world as Christians. It’s precious because it’s truly a balm for those who suffer; it’s radical because in an often senselessly violent world like the one we’re living in, it’s a little unsettling.

Today’s story is a perfect reminder of that truth. It’s a standalone story, sandwiched between two other stories that occur at unspecified times in separate locations. This is unusual – it’s far more common for a Sunday Gospel passage to be part of a much longer narrative arc. And it only occurs in the Gospel of Luke.

We may then very well ask what this despised Samaritan was doing among all these Jewish lepers? Well, Semitic purity culture made for strange bedfellows. Not just lepers but anyone who had a skin condition like psoriasis or eczema or even bad acne had to be segregated from the community. But it was pretty much unheard of for people to live isolated lives back then, so naturally they banded together, with their only commonality being their conditions and the resulting outcast status. Notice that Luke says they kept their distance while yelling to Jesus, out of respect to his status as a Jewish holy man who was not to touch the unclean.

Being made clean then represented not only health but liberation, the ability to reintegrate into society. It must have been such a strange moment of joy and confusion, so I don’t really blame the guys for just taking off and not going back to Jesus. Who knows who they had left behind in their illness, and who knows how long they had had to stay away?

But something very interesting is happening here. The blessing is in vulnerability. Perhaps these people were so astonished by their liberation that they couldn’t help but run screaming away from that previous vulnerability, that previous sense of loss and self-loathing.

We can empathize with that, right? How many times have you thought to yourself, “The sooner I do x, the sooner I can put this whole sorry business behind me� “The sooner things can go back to the way they were?†We’ve all been there; some of us may be there right now. There is nothing wrong with the desire to return to a strong, capable state of being. I am not trying to say that anyone should feel compelled to wallow in helplessness.

But there is no sense in disavowing vulnerability as though it is shameful. This is impossible in the long run, and can make us see the vulnerable as obscene or unworthy.

There is no sense in pushing vulnerability away so forcefully that we forget the one upon whom we rely to see us through in the first place.

It’s not just that the Samaritan remembered his kindergarten manners while the others forgot.

It’s the fact that not only did he say thank you; he turned back; he literally “repented,†that’s what the word in Greek means. He went running back to Jesus – Jewish Jesus, whom he would normally have no contact with, as a Samaritan – and fell at his feet.

Jesus then says something interesting. “Your faith has made you well.â€

It’s a testament to the over-the-top generosity of God that all of them are made clean, all of them are reintegrated. But only this one is proclaimed by Jesus to have been “made well.â€

What could that mean?

Here again the Greek gives us a new lens. The word used can mean to be made well. But it can also have another meaning. It can also mean to save, or to deliver.

Your faith has saved you. Your faith has delivered you.

Saved from what? From the disease? Well, he didn’t say that to the others. It must be deliverance from something else.

Perhaps from the sting of vulnerability, the fear of shame, the sense that he was any less.

Not in the Temple, which he would not have even entered as a Samaritan. Not in the gilded hall of a king.

On the highway, within a group of other unclean people, forced to beg from a distance for liberation and reintegration.

God saw him, where he was, at his worst, and healed him. Not because of a sacrifice, not because of an act of righteousness, but because he asked.

All of them admitted that their need was greater than their pride. But only one realized the beautiful gift of a God who knows our needs even before we ask, and desires only that when we are afraid or in trouble or unclean, whatever the modern version of that may be, we lean into those arms.

What else would you expect from God, our Father in heaven?

This thanksgiving, as we come together in a world that is all too often marked by hate and mass shootings and apathy, name your need for God and for the people you love and who love you. Name that you would not be the same without them. Say thank you. Say I love you. And if you can, say grace before you eat.

I feel the need to say this to you personally, as someone who like anyone has also known unexpected loss, and had to learn the hard way to speak love before it can’t be done face to face. This week I bet a lot of people wondered if there really is anything to be thankful for in our world.

There is.

The Law of our Land

This piece arose out of a decision to rework an earlier entry. For #OrangeShirtDay, I was going to re-post this piece, written shortly after my last full day at the TRC in 2013. I went back and re-read it, and I saw that I had changed in my soul since writing it, which surprised me, as I didn’t feel like my feelings had changed much, but clearly my expression of them has. Today, I find it self-centered and maudlin, focusing more on my own white guilt than on the stories I heard, and expressing more concern with the terror of the past than the continued abuses that shackle indigenous people in Canada today. I don’t think it’s a terrible piece…but I can see, as I said before, how my soul has been changed over the four years since I wrote it. I decided to write something new, and I may even make it a yearly ritual, to see how much my soul changes over time.

Last Sunday, on the 24th of September, I joined with members of my church in a second Walk for Reconciliation. Tens of thousands of people re-traced the route we took four years previously – this time in better weather. We arrived at the Reconciliation Expo, where I participated in my first blanket exercise, led by Kairos. You can learn more about those here. It was described to witnesses as a sort of “experiential history lesson.†For those who have seen it: I was one of the millions of indigenous people killed by disease brought over by European settlers, centuries before reserves and residential schools, which meant I went back to my seat quite early.

We were asked to share our most powerful moment when it was through.

For me, it was the image of two people standing back to back. This represented an indigenous person and a child who had returned from residential school. Children beaten for speaking their language, scourged and silenced for attempting to preserve their cultural identity, despite great bravery and resourcefulness in the face of such abuse, often returned home having lost some or much of that identity. Forcibly stripped of memory and shackled with shame, they often returned to find themselves alienated and confused by what had once been intuitive.

This often forced a wedge between them, their families, and their communities, all of which was symbolized by these two people standing back to back.

Revisiting some of my blog entries from my time at the 2013 TRC events, I am struck by the memories of listening circles and testimonies, of the people who came to tell their stories, with and without fear but never mincing words, and what a beautiful and terrible gift it was to hear the truth.

I am struck by the memories of tears, the memories of emotional exhaustion that was palpable for everyone who entered that blessed site.

I am struck by what for me has become the scent of reconciliation: sage, truly a spirit in itself, omnipresent and enfolding, a healing herb which for me as a settler not only soothes but stings, as so many medicines do, calling me to not only pray for and contribute to the healing of others but to be healed from the soul sickness I carry, being complicit in the system of colonialism that once was and that continues to be.

I am struck by the mixed feelings of uncertainty and comfort: uncertainty because I walked among indigenous people as a foreigner, and yet also felt at home in the smells of medicine and the sights of Coast Salish art and regalia and the sounds of drums, because I grew up hearing these songs and seeing these animals and smelling these smells (sage smells like healing; cedar smells like home).

In my un-erasable foreignness I remember the all-encompassing arms of home embracing me when I stepped off the plane after my emotionally turbulent adventures in England, the land of my ancestors, and once again saw the art of Bill Reid; when I rode over a bridge and saw the fir trees; when I re-acquainted myself with the bigness of everything here that sustains me and the people who have cared for it for thousands of years.

And in the ocean of these spiritually tangled memories, I remember Audrey Siegl’s joy in May when I told her it was my first time singing the Woman’s Warrior Song, the unmitigated delight of her embrace, and my own surprise at her spontaneous welcoming of my voice: “Oh! I have to hug you!â€

I am a settler child…and I belong to this land. I am bound to her laws, and reconciliation is only one of them.

And yet, I suppose, in a way it is the only one.