Archive for the 'NEWS' Category

Lately I’ve been listening to a lot of Lana Del Rey. I’m really not sure how I feel about her. I mean – I am sure about the feelings I get when listening to her music, but I’m not sure about how I feel about them!

I was trying to explain to my husband the other day what happens to me when I listen to music that affects me emotionally. Since I was a little girl I would create landscapes and atmospheres in my mind based on what I was listening to. The first time I remember doing it, I could have been as young as four or five. Mum and I were listening to the absolutely stunning score for the movie The Mission. I think it’s still my favourite movie score ever. I can remember crafting an entire narrative with unicorns, evil serpents, something like a Roc – all taking place in a backdrop which, when I watched the film years later, was not entirely dissimilar. That was not particularly shocking – there were indigenous musical patterns and drums underlying the whole thing – although I did find that years later, the first time I heard Bjork’s “Joga,” the landscape I saw in my head was almost exactly what I saw the first time I saw the accompanying music video, which was a bit shocking!

Since then I’ve continued to have these flights of fancy when I listened to certain songs. I’m sure I’m not at all alone in this. This is part of why when I discover a new song I often listen to it over and over again. I love exploring a new country in my mind, and getting to know every part of it.

Although there are too many songs over the years to remember which ones really affected me, some of them do stand out, either single pieces or whole albums. The first pop song to do it was probably Seal’s “Kiss from a Rose.” I can’t exactly remember what I first saw, but when I listen now I can see a lighthouse, almost lost in billowing white mist and a grey sea. Later song-countries I can remember quite vividly are the green sky and crashing ocean of Celine Dion’s “Miles to Go,” dark blue moonlit and shadowy forest in Sarah Mclachlan’s “Elsewhere,” the early Romantic-era garden in Loreena McKennit’s “Courtyard Lullabye,” the dark bedroom in Jann Arden’s “In Your Keeping,” and the grey shifting shadows and painfully white bathroom in Live’s “Lakini’s Juice.”

Today, I’ve noticed a trend in the music of young female singer-songwriters like Florence Welch and Lana Del Rey. I feel that they are tapping into something that similar artists from years past tried before, but are adding more layers – either with reverb, orchestral scoring, or electronic, driving drum beats – creating vast cathedral-like spaces. I could spend hours wandering in these spaces. I never get tired of Florence’s music in particular, especially on her album Ceremonials. I loved Between Two Lungs, especially for “Cosmic Love,” which transported me to similarly dark forests, laid over with red and orange and twinkling lights. I find her music videos are similar to what I see – they’re both fanciful and dark. Ceremonials, though, was an entirely different experience. “Only if for a Night” was amazing – nighttime outside a place that looked quite similar to Ely Cathedral, only lit up from inside by something unseen. Like Florence’s narrator I danced on the green grass outside under the stars. My favourite track off that album, though, is “Never Let Me Go.” I lay beneath a great blue ocean, all alone on a sandy bottom, watching knives of moonlight cutting through to paint my face. I also listen to “Over the Love” on a loop, seeing a long dark room in a mansion at night, lit only by the light coming in from outside, some of which is white but a tiny portion of which is green, of course. (It’s off the Great Gatsby soundtrack).

Shortly after Ceremonials came out, I was visiting my friend and she showed me the video for “Blue Jeans.” I thought it was one of the most gorgeous videos I’d ever seen (I adore music videos) and although I briefly forgot about it, I re-discovered Lana Del Rey after hearing her sing “Cola.” I started exploring her a bit more, and found that her Hollywood influences – what makes her music sound so expansive – affected me in a similar way to Florence. The first song that really took me somewhere was “Gods and Monsters,” which I listened to over and over. I see a vast red and black landscape of treacherous peaks, kind of like Utah or New Mexico, unfolding before me. There’s nothing there – it’s barren but somehow beautiful and tempting. And now I’ve discovered “Young and Beautiful,” which has yet to carve a place in my head.

All of this is by way of saying that my feelings for Lana Del Rey are odd, mostly because I love her music so damn much and yet I’m not sure how I feel about her lyrics, which are often a bit weird and unsettling to me. I really am not the kind of person who can just ignore lyrics or something that bothers me about music. I’m picky that way – there are some bands or singers whose tunes I love but whose lyrics are just awful, and I actually feel a sort of guilt listening to them. I also feel guilt sometimes when I listen to an artist who I think is personally odious or a jackass. I don’t find Lana to be odious, but I do find her personally to be vacuous and pretentious. I know part of it comes from a persona she is cultivating, but it doesn’t seem to really work. It’s definitely not as meticulously crafted as other artists’ personae.

I’ve been playing with the idea that for me perhaps Lana represents the sort of thoughts that all of us court but may not always allow to the surface. In her song “Young and Beautiful,” for example, she asks, “Will you still love me when I’m no longer young and beautiful?” This bugs me – do we ever become unbeautiful when we become old? My inner feminist shrieks, “No! And anyone who says you’re not should be thrown out on his ear.” And yet I’m not naive enough to pretend people don’t worry about it sometimes, or indeed that I don’t! We all wonder about that day when we look in the mirror and don’t know who we are anymore. To be fair to Lana as well, she follows it up with “I know you will.”

Likewise, in “Gods and Monsters,” she sings from the point of view of someone who seems incredibly reckless, wanting to be saved by a man and shot full of drugs, wanting “innocence lost.” Again – a bit of an odious message for me…and yet I can’t pretend honestly that I’ve never sought out that part that wanted that last veil ripped away roughly. I think it’s part of our psyche.

Maybe, then, Lana sings to “the darker part.” I gotta have someone singing to it.

-Clarity

PS Although Florence’s music has definitely brought me close to God at times, I find the one composer that makes me see God without fail is Lauridsen – particularly his “O Magnum Mysterium” and “O Nata Lux,” both of which I listen to at Christmastime to reflect on the Incarnation. -C

A whole pile of my friends graduated last night, and it was a great pleasure to be there…even though at one point, I thought, “I should be sitting over there.”

A whole pile of my friends graduated last night, and it was a great pleasure to be there…even though at one point, I thought, “I should be sitting over there.”

It was right when the inimitable Rev. Dr. Pat Dutcher-Walls was reading from Genesis 1 in Hebrew. I was already messed up from the absolutely amazing experience of playing “Testify to Love” and the whole church getting up and clapping and singing along with us. Hearing what I heard on my first ever day at VST as a shy and nervous first-year was too much – especially when Pat choked up just briefly at the end! But of course, I was glad too, because I’m not quite ready to leave yet – not emotionally. I couldn’t have done the work that needed to be done for me to graduate this year – I wasn’t willing to take three summer courses last year (I was kind of getting married) OR five courses in one of my previous two semesters. I also need to know more about what’s going to happen to me. I’m not sure about how much longer my discernment group has to decide about me, but I can’t imagine it will be later than August. Then I’ll know if I’m going on to Examining Chaplains and the Executive Archdeacon. I know I won’t be going to ACPO until at least this time next year – with some of my friends! It’ll be awesome if I make it through.

As I listened to Archbishop John Privett’s awesome address about seeds, I reflected on the song I wrote at the beginning of this year, which was also called “Seeds.” I often forget about it and haven’t played it in a very long time. That should probably change.

As we rose to applaud and thank Wendy for a wonderful six years of leadership, I also thought about her amazing hospitality in letting me come in and sit down to talk with her the other week in her office, when all I meant to do was say hello. Her presence this year has been such a balm to me, especially during the Tuesday Eucharists. There would usually only be three or four of us at those services, and as she preached to us, she would take care to look everyone in the eye – and not just a glance, but a full on look that would last several seconds. There was only one day when I couldn’t look back at her, and that was one of those days where the whole world was grey and I was stuck at the foot of the Cross, wondering how it could be possible to talk about Easter morning. Of course, she always preached the good news, but good news never comes without a price.

It’s ours to pay, but I’m glad to pay it – because in God through Christ the price is transformed. Our lonely burden of pain becomes a shared burden. God carried hatred, betrayal, pain, and death in God’s own tender flesh.

The first real song I intentionally wrote about God reflects this: in a wood that is decimated by fire, new shoots grow out of the ash. It is only through the fire’s cleansing that they can grow so rapidly. “Out of death, into life.” God knows the feel of the flame, and in Pentecost, which is approaching, we are given some of that new fire. Somehow we are given back the sweet pain that God experienced as we struggle to bring the world the truth of the kin(g)dom: that things which were cast down are being raised up, and things which had become old are being made new. “Very truly, I tell you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit.”

So con-grad-ulations (ugh, sorry!) to all of my friends who graduated. I’m pullin’ for ya. And I’ll be up there next year – and next year it’ll be in an Anglican Church, likely my own.

Po-freakin-etic.

-Clarity

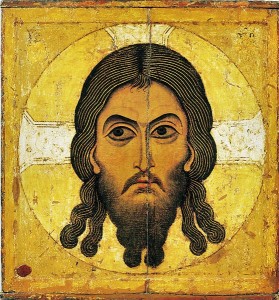

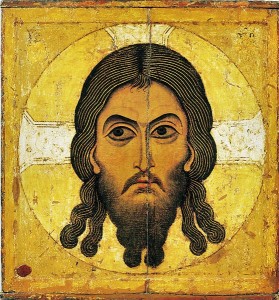

Source: Wikipedia

Hundreds of years ago, a face was painted on a board. It is highly unlikely that the artist could have guessed I would be contemplating it as a young woman in the twenty-first century not once, but twice, in the hopes of copying it as a novice iconographer. My first attempt, done during a very stressful period of my life, was both beautiful and heartbreaking. The icon itself, though it has stayed the same year after year, has changed so much in my own eyes.

The icon is the Holy Mandylion. Christ’s dark face stares up from a circle of gold. My first time was done in acrylic on a very simple canvas, layered over with clear varnish. It was consecrated on Palm Sunday, 2008. The process had been amazing for me, and so during the summer of 2011 I undertook an icon class to paint the beloved face again. Before we actually laid our natural pigments to the board, however, we participated in a group meditation on our blank boards. What came to me was so profound I sought to look deeper.

This paper seeks to understand the significance of the meditation I had on the blank board, using both the tools of my own mind, and those provided to me by a study of iconography and its history.

I began with the injunction to pray for those who had upset me and forgive them. The professor also encouraged us to keep in mind creation, and the beautiful stories of Genesis. The meditation came to me very quickly, and I have transcribed it as best I could here.

I feel immediately connected. I am filled with light, and everyone who has ever angered me is lifted up. I embrace them.

I come to the board but it is not Genesis. It is John’s Prologue: In the beginning was the Word. The tiny bumps on the board are like stars in a clear sky. It is the darkness which cannot be overcome. He is my light. I pour life into this board: blood of light. I bleed life into the board: God tears at my heart and dances me into kenosis.

The board seems to move. I find I want to close my eyes. I’m not a very visual person when I pray…but I want to be. I am always overstimulated by images – they have so much power over me. If I can meet God with eyes open and not be burned away I may understand that…I don’t know. How can white become gold? How can light be more than light? Light is light but it is infused.

At this point in the meditation I tried to turn my focus onto the print we were given of the Holy Face. After the pure whiteness of the board, however, the darkness, richness and deep colours of the Face were almost unbearable. I was reminded of Moses and his veil as he came down from the mountain. I decided to put the board over parts of the Face to help me focus better.

I put the board over his lower face. Now I can only see his eyes. One looks into me, the other elsewhere. One is human, the other is more, yet both are both. His eye meeting mine is the eye of God that shone from one human face to another, and the eye that looks up is a human eye that knows fullness of being – the human as God intended, the human in perfect union.

I move the board to the right side of his face. His eye looks into me. There is only a tiny pinpoint of light in it. His human eye looks like the beginning of all things. His eye knows the all, and everything in me.

His left eye looks upward with less softness. There is determination, as though listening. It is commanding. From down here where I sit on the floor, he looks up at some of my classmates. He is looking at The Other, the one he served and the one I must serve. There is no choice. This way is the way of God. Not necessarily “Christianity†per se, but God’s whole way of being: service. This way is the only way to union. We can’t meet him halfway if we want to be true followers. This is amazing, because his human eye looks into me and knows my faults, knows my humanity. We will always be struggling between the two: who we are and what we need to become. He who was both is here to guide…and he understands. Something else I see that is truly beautiful arises. Just as his human eye has that tiny spark of divinity in it, the “God side†of his face has lips that are full and red. These lips seem ready to offer me a kiss of peace: Peace be with you.

Thank you, Lord. I believe.

My Own Interpretation

Despite the fact that I ruled out Genesis in the meditation, on further reflection I do find pieces of it here. The sky was dark and full of stars but ultimately still empty, devoid of moon or any reflection. It is a pregnant sky, waiting to burst from its potential.

The questions about light becoming gold and how light can be more than light seem very primal to me. The real question seems to be, “How can nothing become everything?†It also reminded me of the Incarnation: how can the pure light of one human life – Mary – suddenly become infused with gold, the holiness of God? How does this one beautiful creature suddenly become what the Orthodox call Theotokos?

Not being able to look at the Face after the whiteness of the board was very significant for me. It really did feel like staring into the Transfiguration, or trying to look into the upper clouds on Sinai. It also reminded me of Genesis, that humans were the last creatures to lay eyes on God.

I had heard from an unremembered source that the somewhat mismatched eyes of Christ in many icons are done deliberately, precisely to illustrate his dual nature. My mind clearly fixed on that and contemplated the presence of the Word in a human life. In fact, the word I focussed on during the course of the meditation was “Wordâ€, although sometimes in my mind I settled on the gorgeous Logos.

This meditation for me was incredibly full, and on its own it helped me greatly, since there was an imperative within it – that of service. I was curious, however, in the fact that I had begun to focus on John’s Prologue. The passage’s connection to the icon did not seem immediately apparent at first, and so I decided to consult some other sources to see what I could learn from other, more adept and educated minds than my own.

Further Study

Seeking God through the created image is something that has walked alongside Christianity for a very long time. We can never be entirely sure how long, though, since although we are aware of Christians producing art by the 3rd century, it is difficult to recognize art that could be called “Christian†before then.[1] It’s also uncertain as to whether or not the early Christian church was supportive of Christian art. Bursts of iconoclasm occurred in the eighth and ninth centuries, as well as attempts to ban images altogether. Despite the uncertainty, we know that Christian art began to emerge, and early in its inception it was much like contemporary Roman art.[2] The main difference is that Christian art, while keeping the forms of Roman art, began to develop biblical subject matter in a way that had not been seen before. Robert Cormack observes that, “[T]he discussion about early Christian art has been one about the ways in which art can change its meanings more easily than its forms.â€[3]

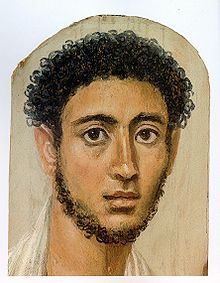

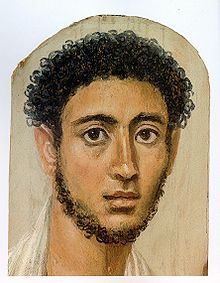

Examples of the medium in which icons first came into being – panels painted in tempera on a textile with gesso as a base – can be found at Fayyum in Egypt in Roman cemeteries. The paintings, some of them triptychs with gods or goddesses surrounding a face, were thought to be portraits of the dead that had been mummified.[4] The close proximity of these paintings to the monastery of St. Catherine at Sinai suggests to Cormack that “in developing art in the service of the new faith, Christians had in their sights an effective medium already in religious use.â€[5]

Source: Wikipedia

In Christoph Schonborn’s God’s Human Face: The Christ-Icon, Schonborn observes in the Fayyum paintings “a change influenced…by the Jewish-Christian view of man.â€[6] Looking at a third century mummy portrait as provided by the book, I am struck by the similarities to the Holy Face. This face seems lit from within by a deep rosy glow, and the eyes are very large and full of life. The nose is long and thin, the lips full and potent but the mouth small in relation to the rest of the face. These large eyes are a way to demonstrate a deep spirituality – an “inner seeingâ€[7] – while the small mouth demonstrates that the deeply enlightened have no need for dialogue. Remembering the writing of my first icon, I was attentive to the points of light around the face and noticed they were similar if not the same to where they had been on the Holy Face: several around the eyes and a few at the bridge and the tip of the nose. This contributes to the realistic aspects of the portrait, but also hints at an almost chakraÂ-esque view of the human facial form. Points of light become points of energy concentrated inward and yet radiating outward.

The use of these contemporary commonplace mediums to communicate the message of the divine in human form seemed to me to echo many of the basic elements in the early Christian community. The most obvious one would be the theme of the ordinary being transformed. An ordinary home is consecrated during the agape meal. An undesirable such as a leper is welcomed into a loving community. A form of painting becomes a “window looking out upon eternity.â€[8] None of these things are completely turned into new things. The house remains a house, the leper remains a leper, and the painting remains a painting. They are deeply changed within, however. The action and intention of those who perform the change infuses these ordinary things with light. These early icons were still religious paintings of those who had died or gone into the next world, but they were not simply a record to help the dead find themselves again. Instead they were kept and treasured as links to those they represented, kissed and wept over, loved and cherished. Intriguingly, Cormack also notes that “The reliance of the people on icons as a window to heaven was gradually seen as a subversive threat to the authority and control of the state.â€[9] Here transformation becomes infused with the light of empowerment.

The exploration of the icon’s origins provided me with a fascinating window into the history of the Face as it looked to me during my meditation. The transformation of the simple panel paintings into something that helped believers into a new way of seeing seemed to call out to me to continue to transform my own life through faith. However, I still did not understand exactly why the Face affected me quite the way it did. I still wanted to know how the painting of our Lord’s Face as it was presented could bring me closer to God. To answer this question, I turned to Schonborn again and explored his summary of the Christological arguments that helped to develop a new way of looking at personhood, which had implications both for faith and for human interaction.

Schonborn presented through Gregory of Nyssa a great answer for why I could not fully look at the Face. While explaining Gregory’s exposition on the nature and essence of the divine persons, Schonborn finds a template for the development of a theology of the icon:

“[T]he contemplation of the countenance of the Son imprints in our heart the seal of the Person of the Father. Because he is the Son of the Father, the Father becomes visible in him.â€[10]

Gregory of Nyssa uses the image of a mirror to explain how we might understand the Son’s relationship to the Father: that the image in a mirror is the same as the original and yet is not the original. Since the image is the same it can be honoured but not worshipped per se – a way of describing how many use icons in worship.

I was endlessly curious as to why I turned from an immediate Genesis interpretation to a Johannine one. I found that John’s Prologue was an oft-cited source for many of these early Christological arguments, and reflected on the choice of the writer of John to refer to the Word (Logos) becoming flesh (sarx) rather than man (anthropos). The writer of John speaks rhapsodically of the whole universe being alight with Logos/Christ. This to me affirms a tenet of iconography which states that everything has been created by God, and that it therefore must be viewed as good by the believer/writer, that it participates in goodness.[11] Iconographer Matthia Langone notes that the icon “points to the reality of the Incarnation, the goodness of creation and the dignity of the human person.â€[12] The church father Irenaeus spoke of creation revealing the one who formed it. For Cyril of Alexandria, “the flesh [was] not an ‘extrinsic cover’ but belongs to the very identity of the Logos.â€[13] In defending the use of icons during what Schonborn refers to as “the gathering iconoclastic stormâ€, the eighth century saint Patriarch Germanus also refers to John:

“Of the invisible deity we make neither a likeness nor any other form. For even the supreme choirs of the holy angels do not fully know or fathom God. But then the only-begotten Son, who dwells in the bosom of the Father (cf. Jn 1:18), desiring to free his own creature from the sentence of death, mercifully deigned…to become man. … For this reason we depict his human likeness in an image, the way he looked as man and in the flesh, and not as he is in his ineffable and invisible divinity.â€[14]

For Schonborn, all iconophilic arguments could be summed up as such: “[T]he Incarnation means that the Eternal Word has assumed a visible likeness.â€[15]

I was delighted in the soul-resonance I felt with these early church fathers and the use of John. Christological arguments aside, I found another excellent source for reflection in Henri Nouwen’s soul-stirring Behold the Beauty of the Lord. Deeply moved by his experiences praying with Russian icons, Nouwen reaches zeniths of beauty in prayer that speak to my heart. His meditation on the Saviour of Zvenigorod struck chords in my mind:

“The eyes…are the eyes of the Son of Man and Son of God described in the Book of Revelation…He is the light of the first day when God spoke the light, divided it from the darkness, and saw that it was good. (Gen. 1:3) He is also the light of the new day shining in the dark, a light that darkness could not overpower. (Jn. 1:5)â€[16]

For Nouwen, this was a deep celebration of the Incarnation: “We can see God and live! As we try to fix our eyes on the eyes of Jesus we know that we are seeing the eyes of God.â€[17]

Conclusion

After further exploration I have come back to my own little room, in which one candle burns for Christ all day and all night. I suppose, though, that one thing has changed: this icon now hangs within. As Nouwen observes, “Icons are painted to lead us into the inner room of prayer and bring us close to the heart of God.â€[18] As iconographer Matthia Langone observes in an interview, “[T]he icon…is like a door one leaves behind as one crosses the threshold into another dimension of reality.â€[19]

Exploration of the theology of icons has brought me into a beautifully close relationship with the divine, for I feel that I have not missed out, by virtue of being born two thousand years too late, in seeing the face of the Lord. Because he came among us, he will forever be one of us, and he will forever be before us should we choose to look. In John’s Prologue we are gifted with the beauty of his primacy, and with John’s faith and comfort in knowing that his Lord’s life was lived with complete intentionality from start to finish. Indeed, when I looked into that face, I could not believe anything otherwise! There from one face burn the two perfect eyes of my Beloved: the one that looks into me and sees me for what I am, and the one that looks beyond me and sees all of us for what we could be if we only follow. This is the nature of God: to be known by us, and to call us to honour our creation (all creation), and to strive for our intimacy with the one who made us, who came among us, and who burns within us.

Amen. I believe…and I see.

Bibliography

Â

Behold the Beauty of the Lord: Praying with Icons, Henri J.M. Nouwen

Ave Maria Press, Notre Dame, Indiana. 1987/2007 (revised edition)

God’s Human Face: The Christ-Icon, Christoph Schonborn

Ignatius Press, San Francisco. 1994

From the German translation, Die Christus-Ikone. Eine theologische Hinfuhrung

(Novalis Verlag, Schaffhausen, Germany, 1984)

Originally published as L’Icone du Christ. Fondements theologiques elabores entre le Ier et le IIer Concile de Nicee (325-787 AD)

(Editions Universitaires, 2nd ed. Fribourg, 1976, 1978)

Painting the Soul : Icons, Death masks, and Shrouds, Robert Cormack

Reaktion Books Ltd., London, UK. 1997

[1] Painting the Soul, (Robert Cormack), 64

[6] God’s Human Face, 24

[7] “The Way of the Icon†classroom notes, July 11th/2011

[8] Behold the Beauty of the Lord, Henri Nouwen, 24

[9] Painting the Soul, 19

[10] God’s Human Face, 31 (italics orig.)

[11] “The Way of the Icon†classroom notes, July 11/2011

[12] “The Way of the Iconâ€, 2, interview with Matthia Langone conducted by Karen Walker, June 2004 (article reprinted with permission from the Thomas Aquinas College Alumni Newsletter)

[13] God’s Human Face, 81

[16] Behold the Beauty of the Lord, 81

[19] “The Way of the Iconâ€, Walker/Langone, 7

Two years ago, on Trinity Sunday, I was scheduled to give the children’s talk at Christ Church Cathedral in Vancouver. I had specifically asked to do so because of something I had learned in Richard Topping’s Constructive Theology class at the Vancouver School of Theology. To explain the doctrine of the Trinity to the children – and the adults – I had the Cathedral’s dean and associate priest join hands with me and form a circle, which turned as we all shuffled to the right, facing out. It looked silly, but was a dynamic illustration of the concept of perichoresis, a Greek term introduced by the Church Fathers (and Mothers) which is finding new meaning among contemporary theologians.[1] Traditionally, the definition has to do with mutual in-dwelling, but the word also has connotations of perpetual movement, or “circulating around.â€[2] It was used by Maximus the Confessor to refer to how the human and divine natures in Christ functioned, by John of Damascus to describe an “interdependent, dynamic, mutual indwelling of the three personsâ€[3], and was taken up by other patristic thinkers “to show 1) singleness of effect within a mutuality of action and 2) permeation without confusion in the human and divine natures of Jesus.â€[4] Later, during the debates over the concept of hypostasis, the word began to be applied to the Trinity in an attempt to resist tri-theism, seen as describing the mutual indwelling, without confusion, of the three persons within each other.

Learning about perichoresis helped me to develop my own ideas around the concept of the Trinity, which is a concept that had always been mystifying to me. The ancient controversies and its mystical qualities seem to have made it inaccessible to many modern and postmodern people. Entire denominations such as the Christadelphians, Christian Scientists and Jehovah’s Witnesses have even dropped Trinitarianism altogether for various reasons, and they were not the first to do so – other groups such as Arians, Gnostics, and Cathars were the original skeptics. I personally feel that Trinitarianism is a core concept of Christian faith precisely because of the way it has been communicated to me through Anglicanism.

Anglicanism as a faith tradition has strong roots in Catholicism and the Nicene Creed. The stunning hymn “St. Patrick’s Breastplateâ€, with its celebration of “the strong name of the Trinityâ€, demonstrates the love St. Patrick had for the concept. Julian of Norwich, too, saw her vision of the crucified Christ as a unique revelation of the Triune God. However, as the Enlightenment marched steadily onward, Western Christianity began to lose touch with this doctrine, seeing God in increasingly monistic (and solitary) terms. Deism was likely the culmination of this view of an abstract, absent God. Over the years, we have been reclaiming the doctrine, and Anglicans in particular have worked with their friends in the East to rediscover something which remained largely un-lost in the Orthodox Church.

In the Anglican mind, the doctrine of the Trinity appears to be linked to several different notions. The primary notion, which influences all others, is community. “The renaissance of [T]rinitarian theology in recent decades brought a renewed awareness that God is fundamentally relational, that is, God is a communion of Persons, a being-in-relation whose sphere of generosity and life is the economy of creation and redemption.â€[5] Anglicanism has always sought to be a via media of Christianity. This involves accommodating a great diversity of beliefs. Many of our conflicts of identity have been based in our struggles between small c Catholicism and Protestantism. There has also been a fairly consistent and somewhat healthy dialogue between the adoption of Enlightenment-era skepticism and a more mystical, deeply prayerful life of faith. No matter what identity we choose for ourselves, if we identify as Anglicans we identify, too, as a being-in-relation, one that involves constant movement and negotiation, like a wheel or the tides (although generally our movements as a church tend to be less peaceful!) As we model this form of being-in-relation to each other, God uses the Son and Spirit to model being-in-relation to us, and, reflecting perfect balance: “[Th]rough the missions of the Son and the Spirit…God draws the church, all humankind, and all creation into this divine life and so into salvation, as this has been traditionally called.â€[6]

Community for many Anglicans refers not only to the community of believers, but to the Eucharist as well. One of the simplest ways to discover Anglican theology is to examine a church’s worship services and liturgies. In 1995 the International Anglican Liturgical Consultation met in Dublin to discuss recommendations for Eucharistic revision. The resulting report, published the following year, sought to help guide revisions of Eucharistic prayers by having them reflect certain themes, which included the Doctrine of the Trinity.[7] While explaining the reasons for the change in format of newer Eucharistic prayers, Moroney describes the Eucharist as the culmination (or “fruitâ€) of the work of the whole Trinity as well as an anamnesis (a nod to both the Catholic and Reformed views of Eucharist) by way of three different prayers, two of which focus on the different acts of the Three Persons, upheld by their unity, and one of which is less specific and focusses on the Trinity itself. The Irish Church is a prime example of the diversity of Anglicanism: in a country that is largely Roman Catholic, Irish Anglicans have adopted a more Reformed attitude as a testament to their own minority identity. An exploration of early Celtic prayers reveals that it was common to seek the Trinity’s blessing on every-day activities such as washing one’s hands or stoking the morning fire; it would be no surprise to me that further development of Eucharistic prayer would request the Trinity’s presence here as well. Moroney does not explicitly describe how it is that the Eucharist is the fruit of the Trinity. When I reflect on the work of the IALC, I note the wording in some of the different Anglican prayer books in use today. Although the 1962 Book of Common Prayer does not provide notes on the format of the liturgy in the same way that newer prayer books do, a Trinitarian echo can be found at the end of the Eucharistic prayer:

“And we pray, that by the power of the Holy Spirit, all we who are partakers of this Holy Communion may be fulfilled with thy grace and heavenly benediction; through Jesus Christ our Lord, by whom and with whom and in whom, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, all honour and glory be unto thee, O Father Almighty, world without end.â€[8]

Newer prayer books are more explicit. In the explanatory notes preceding the form of the Eucharist, the 1985 Book of Alternative Services makes it clear that Eucharistic prayers, while prayed to God, illustrate the work of Christ, and celebrate the Church’s union with Christ in celebration through the Holy Spirit.[9] Likewise, the New Zealand prayer book states, “We give thanks to the Father, remember Christ, call upon the Holy Spirit, unite ourselves to all the faithful, and share God’s food and hospitality.â€[10] In a very real way, the Trinity is present at the Eucharist, and therefore part of the saving, the remembering, the rejoicing, and the looking forward to the heavenly banquet. I am reminded of the words of John Bell’s hymn, “Today I Awakeâ€: “Today I enjoy the Trinity ‘round me, above and beneath, before and behind: the Maker, the Son, the Spirit together, they called me to life and call me their friend.†The intimacy in this relationship gives rise to a great sense of hospitality among believers and God. The constant shifting implied by the concept of perichoresis seems to harmonize well with the cross-cultural significance of circles and wheels and their sense of balance. God, many-faced like Janus, reveals Godself to us in different ways, attesting to a great hospitality of interaction and invitation. This invitation is a key component of Trinitarian faith. Rowan Williams has said that being Christian “is believing the doctrine of the Trinity to be true, and true in a way that that converts and heals the human world,†but it is “not a claim about the totality of truth about God or about the human world.â€[11]

This sense of intimate, inviting, hospitable, saving, and rejoicing community is what I believe the church is called to be and what the Anglican Church strives to be. Rather than focussing exclusively on the bizarre intellectual gymnastics one requires to navigate the old controversies, a focus on God’s relational qualities and shifting but never compromised identity gives the doctrine of the Trinity new life for me and many others. Formerly Wiccan, I observed and marked the turning of the seasons with a deep reverence for the strangely moving stasis (or circle) of life on Earth, a movement that worked for the preservation and betterment of itself, not a singular Other but the many diverse parts of the whole working together. It was amazing to me to consider that God, too, is part of a strangely moving stasis where all aspects worked in unity with each other for the betterment of the whole and those sustained by its movement. My Anglican identity and my Celtic ethnicity provided a fertile ground for growing and nurturing this intimate relationship. I am empowered and sustained by the singular God that addresses me in three different ways: “Creator, Redeemer, and Friend.â€[12] It’s stunning to me that these three faces are all part of one great heart, which loves me and everyone in such a diverse and unified manner. The Trinity, then, is my strength.

“I bind unto myself today the strong name of the Trinity,

By invocation of the same, the Three-in-One and One-in-Three.â€

[1] “The renaissance of interest in the Doctrine of the Trinity over recent decades is well known.†Don Saines, “Wider, Broader, Richer: Trinitarian theology and Ministerial Order,†Anglican Theological Review 92 (2010): 515

[2] Dwight Zscheile, “The Trinity, Leadership, and Power,†Journal of Religious Leadership, 6:2, (Fall 2007): 43 Rev. Zscheile is a Lutheran minister, but I’ve found his reasoning to be fairly congruent with an Anglican viewpoint, and since the Anglican Church of Canada and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada are in communion I felt that was reason enough to trust him.

[3] Ibid., 45 (emphasis added).

[4] Jim Horsthuis, “Participants with God: A perichoretic theology of leadership,†Journal of Religious Leadership 10 no 1, (Spr 2011): 87

[7] Kevin J. Moroney, “Elements of an Irish Anglican Eucharistic Theology,†Worship, 84 no 6, (N 2010): 514

[12] Rev. Dr. Ellen Clark-King’s substitution for “Father, Son and Holy Spirit.â€

Tonight I had the great privilege of playing at the St. Paul’s Labyrinth. It’s a beautiful liminal space where people of all stripes show up to walk or just sit and listen.

I brought with me a couple of hymns (including a re-purposed praise song – I love making up different lyrics on the fly!), some of my own stuff, and a bunch of Florence and the Machine. I can’t help but wonder if she’s like U2 and putting secret theology in her songs. Here, judge for yourself. I played this, this, this, and this. I think any praise band could get away with singing those.

I’ve been thinking a lot about opals. I thought of how pretty they were at random yesterday, and then went on Etsy looking for opal jewelry. My Mum has an opal ring she’s promised I’ll inherit, but I didn’t feel like waiting for that! Besides, the big 3-0 is coming up next year, so I’ll have a suggestion for a certain someone, heh heh.

Anyway, I was drooling over all these opals, and was thinking about my favourite colour, which is basically mauve but with a bit of blue in it. I love it because it seems like a mystical colour to me, and I had heard before that colours like that are actually really hard for the human eye to focus on. Maybe that’s why it seems mystical to me. Opals kind of give me the same reaction – they’re mystical somehow. They seem ordinary until they hit the perfect light, and then they contain every colour.

I started thinking about how Christ is like an opal – within an ordinary human body was contained a gorgeous web of stars, and because of the Incarnation and the Resurrection, all people now contain these stars. We are all hallowed, and God is human-ed.

A poem might follow.

-Clarity

“[Anglicans] are…a deeply praying people. We pray constantly throughout the day. We believe our healthy spirituality depends on continuous prayer. Our people are also a mystic people. Finally, we are a people deeply immersed in the world – we get our hands dirty.â€[1]

Anglicanism is a faith that, at its best, walks while singing. Walking is what it does in daily life, moving forward along whatever road it has been given and (again, at its best), choosing to live the life (walk the walk) it proclaims through its singing: the life of the kingdom of God. Neither of these two actions, in the Anglican mind, should be separated.

Our walking song is our sacraments. A song is something that is appreciated with the mind and emotions, but a song also involves the body. A person does not need to be trained or even particularly talented to produce a song, but the beauty and transformative power of a song is enhanced when training, talent, or mindfulness are present. Our hope is that our song (which should really be called a hymn, as the able performance of it should point to God and not to ourselves) is sung in harmony with God’s voice and brings about transformation in the lives of all who pass by on the road we walk.

Our walking hymns may be sung with great awareness of their context in the world (on the road), but they are not the same as the hymns of the world. I feel that in their uniqueness, they call attention to profound models of justice. This justice is a natural outgrowth of Anglican spiritual practice as grounded in regular liturgy and in theology developed in, nourished by, and sustained by liturgy.

Once, regular religious observance was seen as part of the bounden duties of a good citizen. It was morally edifying and necessary for good character formation. It would help to contribute to a more stable society, which was envisioned as homogenous, socially structured through a certain form of hierarchy, and ideally Western. Today, at least in Vancouver, this is no longer the case! Religion in general stands in opposition to the slowly changing tides of this region. Spending time singing songs on the road is seen as distracting from the main objective, which is to carve out a place for oneself using all the tools at one’s disposal. Some even consider it distracting from providing for others on the road. However, most Christians and Anglicans in particular proclaim that singing songs of hope cannot be separated from providing for others on the road. Our sacraments provide an alternative worldview, one that at its best is holistic, affirming, transformative, and evocative, calling into reality through our practice the fulfillment of God’s reign. By singing “We shall overcome,†we have and will overcome.

The sacraments of the Anglican Church proclaim, point to, and enact the justice of God’s reign in many ways. For this paper, I have discerned three. The first way is transcendence. The second way is reconciliation. The third way is a form of incarnational wholeness. All three of these are deeply linked – rich harmony lines for our walking song. All three call us into relationships and lives built on justice as “most basically the pursuit of authentic relationships with God, other persons, and with created order itself. From a Christian perspective, the striving for authentic relationships – or justice – ultimately aims at the full mutuality of trinitarian love.â€[2] They teach us to see a world outside our own self-interest, to work for and worship in the spirit of reconciliation, and to hallow and treat with dignity the creation of God.

Transcendence

All sacred activity is grounded on the notion that a reality exists outside of what can be immediately perceived by the senses and the rational mind. Rudolf Otto described it as “non-rational†rather than “irrational,†standing not in opposition to rationality but beside it as alternative.[3] The search for the sacred and ritual encounter with the divine is by definition linked to transcendence of one’s self.

Transcendence is often set up against immanence, but they do not necessarily need to be mutually exclusive in the case of sacredness. As human beings we can seek to transcend the human-created barriers we erect against each other. Jesus did this through his intentional and loving encounters with the unclean and socially unacceptable and Christians are called to do the same. However, the call to transcend moves us beyond even what we can do on the earth. Here, the sacraments mediate our relationship with God, drawing God closer and pushing us forward. While some sacraments do call us to transcend boundaries (all baptized Christians are welcomed at God’s table in the Eucharist of the Anglican Church of Canada; baptism unites us with the priesthood of all believers in every age), many of them teach transcendence through being, paradoxically, both identity bestow-ers and identity transcend-ers.

We are all born into identity. Our genetic makeup gives us a visual and physical identity, and many years of learning and reflection give us a more conceptual identity. Each sacrament bestows or reinforces an identity that we (generally) choose voluntarily. This identity transcends the identities that we are given by circumstance and helps us see, sometimes fleetingly, how God sees us. In baptism, we are brought into the new life of Christ, the life of wholeness as celebrated in liturgy, which transcends who we are as physical beings by putting us in contact with the priesthood of all believers and the great cloud of witnesses. In confirmation, we call upon the Holy Spirit to affirm this identity and continue to strengthen us in our baptismal wholeness and calling. In Eucharist, we all eat from one loaf, each taking separately but knowing that in Christ we are one bread, one body, which died and will be raised, transcending separateness into wholeness. In healing and reconciliation, we affirm ourselves as people in need of care in our brokenness, and transcend by proclaiming the possibility and the eventual certainty of being made whole. In marriage and ordination, we come as singular people, but leave as deeply committed to others, transcending ourselves to become either “one flesh†or the mediator and caretaker of the people of God, no longer existing simply for oneself but for God and God’s people in a radical, cruciform way.

In none of these sacraments is our previous identity denied in a healthy spirituality. This is why it is important to use the concept of transcendence. We are still ourselves, but at the same time, we are more.

Reconciliation

Anglicanism is not a confessional faith. Although we share the creeds, the Thirty-Nine Articles, and the Books of Common Prayer and their revised offspring, we are a faith of incredible diversity. As a people of context and diversity, there is a great need for mutual learning and continued dialogue (multilogue?). In the 20th and 21st centuries, Anglicanism has sought to extend its spirit of reconciliation to where it discerns a prophetic calling for it. In some ways, this spirit of reconciliation is quite counter-cultural. That the Anglican Church remains together to some extent, despite persistent cries to leave those who disagree behind from outside and inside the Church, is amazing in our individualistic culture. My friend Rev. Canon Douglas Williams once said, “Anglicans are good at being heretics, but we don’t like being schismatics.†We’re more than happy to take each other to court over the ownership of church buildings or whether the altar should be fixed or movable, but when a group decides it’s had enough and splits away, it’s far more likely to continue to refer to itself as Anglican.

Sacraments are a profound expression of reconciliation, mostly for the same reason that they are an expression of transcendence. Eucharist and baptism not only call us to transcend our identities, but reconcile us by claiming that we are not apart from God but fully in relationship. Eucharist in particular proclaims that in the coming of Christ, all things will be “reconciled and made new.â€[4] The reconciliation of a penitent is the most obvious sacrament of reconciliation, although it is quite worthwhile to note that a lot of attention is often paid to the penitent, and not as much to the victim.[5] Opposite-sex marriage, likewise, can be seen as a form of reconciliation between the sexes, as demonstrated in a moving liturgy at VST in October of 2012 that used movement, song, and Eucharist to address Jesus’ troubling teaching. Same-sex marriage, as a covenantal relationship, can be a reconciliation with and affirmation of one’s own sexual identity. In these sacraments, we proclaim a God who, in reaching out to us and inviting our reaching back (transcendence) provides love and acceptance (reconciliation). Reconciliation transitions nicely into the last way, which is incarnational faith.

A Body-Positive, Incarnational Faith

Anglicanism has always celebrated the incarnational reality of Christ. Its Eucharistic prayers refer consistently to the good work of God in creation and Jesus’ life as a physical being.[6] In this it seems to have a soft (and sometimes not so soft) echo of its creation-positive Celtic roots ringing throughout the song of the sacraments.

In Anglican theology and practice I have found this incarnational preference highlighted not only in enacted church sacraments but in the desire among many Anglicans for beauty in worship. The stunning churches of England are enhanced by beautiful choral music, clergy and altar vestments are hand sewn by faithful artisans, and “holy hardware†is lovingly cared for over years and years. Where many Reformation era theologians saw excess and profanity, many Anglicans saw in this beauty a foretaste of the beauty of the kingdom. Over the years, vessels, vestments, and buildings have changed, but the attachment worshippers have to these objects, no matter how beautiful or how homely they are, testify to the need and love for something physical to be seen and touched in worship.

Anglican sacraments are profoundly body-aware, if not always explicit in body positivity. The practice of daily prayer and frequent Eucharist hallow the day-to-day present life and the need for sustenance both physical and spiritual. Marriage hallows daily life and the bodies of two people joining together; healing and reconciliation receive people into wholeness. Baptism affirms the reception of the new and offers new clothing for the person to put on – not rejecting the old but sanctifying it as it is. Ordination shows in a profound way the unique hallowing of a holistic life as belonging to the church, and the care taken in selecting individuals shows the care the church has for those who seek this path. Confirmation, through the laying on of hands, also offers the strength of the Spirit for all, and hallows the prayers of the community for the one being confirmed. In this emphasis on corporality, there also run through the prayers a sense of mortality and death. Our combined Catholic and Reformed history employs the language of death in our Eucharistic prayers; in baptism death prefigures resurrection and reception into the community; the priest, as Rev. Harold Munn has articulated it, must model, among other things, death to a congregation and knowingly accept this at the sacrament of ordination; the penitent must die to the old way of living in sin; the bride and groom die to a life lived only for themselves. This is perhaps the most counter-cultural statement the Church makes, living in a world in which aging and death have become the last great taboo.

In these three manifestations of sacramental justice, Anglicanism has found an ethics to aspire to. Aspiring to them is generally the most we can promise. It is significant that in Anglican liturgy, unlike the structure of many Reformed liturgies, the confession does not come at the beginning, but in the middle, and in the Book of Common Prayer is prefaced by “comfortable wordsâ€. God welcomes us by way of being present, speaking to us through scripture and sermon, and hearing our prayers. It is then that we make our confession, and what follows it? Present day and eschatological joy in the Eucharist meal. Immediately following that is our commission to go out proclaiming what we have experienced. In our joyful feasting and our time together, we are invited into new relationship, and called to extend the invitation to the whole creation.

Let us sing on the road, remembering that Jesus may be among us, only to be known for certain in the breaking of the bread.

[1] “Anglican History†classroom notes (Wendy Fletcher), September 14th 2011.

[2] Mark O’Keefe, Becoming Good, Becoming Holy (New York, Paulist Press, 1995), 106

[3] Although the tendency of New Atheist thought is to conflate the two, the vast majority of humankind’s history has been lived in this non-rational mindset.

[4] The Book of Alternative Services, p. 200

[5] Catherine Vincie, a Roman Catholic, has a brilliant article on this topic, “For the Victimâ€, where she suggests the inclusion of alternative liturgies that focus more on the sufferings of victims. It should also be noted that the First Nations of the Nass Valley in instances of wrongdoing will often hold a “cleansing feast†where time is given specifically to victims to tell their story. Although Western people often react with apprehension at the thought of a victim having to confront someone who has wronged them (sexually, for example), it seems far healthier than the Western options, which have too often been secrecy or leaving it up to the victim to forgive on his/her own.

[6] Eucharistic prayers in the Book of Common Prayer and the Book of Alternative Services are explicit and rich in their incarnational language.

I just updated my Soundcloud page, if you’d care to have a listen…

-Clarity

Aaaaaaannnnnnd the ass unclenches.

HAHAHA so sorry, but I just thought I’d be honest.

This is first real day off I’ve had in almost seven months. Since September I’ve been busting my big buns on a zillion different projects, and now I’m free for a couple of weeks before STARTING CPE. YAY! I had a great interview and was accepted to the summer program at St. Paul’s Hospital (although they’ll send you where there’s need, so I could put in some time at other Providence Healthcare locations).

Here’s what I did this year:

VSGlee – I had the great privilege of being on the leadership team for this awesome new student-led choir that came to fruition after the school regretfully had to cut the chapel musician position. It was a lot of work but we had some really great times singing some wonderful music. The year came (somewhat) to a close with our party last Thursday, where much fun was had jamming, playing Glee! karaoke and Super Mario Brothers on Maryann’s Wii, and playing Balloon Ball, which is the nuttiest Calvinball-esque sport ever and involves rolling chairs and a whole wack of balloons. We’re still up to do Convocation, though, which should be a hoot.

Full Time Classes! – In the fall I took Sacraments/LS600, Homiletics (preaching), “Gender in Religious Literature” (to build up a bibliography for a possible ThM), and Leadership Studio (which extended into the Spring). In the spring I took Christianity in Culture (a brilliant course about Karl Barth, the Confessing Church, and the Rise of National Socialism), Prophets/HB611 (for which I just wrote a paper on Ezekiel as a metal-head, HA), and the Spirituality of Healing (for which I wrote a paper on Exorcism and Self-Harm). The work was tough – I found it very difficult to give all the classes the time I felt they deserved. Oh well – that’s what Continuing Education is for.

Work Study – This was the first year I didn’t work in the library for my work-study position. I took over a revised version of what was once called the Sacristan or Worship Assistant job. After the musician’s position was dropped, this position was revamped to include co-ordination with VSGlee. Although it didn’t explicitly say that I had to actually perform with VSGlee, I did it anyway. It made the synthesis of information much easier. My other duties included caring for linens and worship spaces, consulting with weekly worship leaders, purchasing bread, wine, and grape juice, and setting up the space for our worship each week. It was complicated at times because I’ve never been particularly good at setting my own hours, especially when I have to calculate random chunks of time spent doing minor things like folding or ironing. I made it work, though.

Field Education – Since I was doing Leadership Studio I got to be fully involved in a field education project this year! I had chosen St. Paul’s and spent the summer there, ostensibly doing TFE3, but I don’t know if it’s going to be counted at all. (CPE should take care of any inconsistencies). As September started I continued doing what I’d always been doing, which was showing up for worship on Sunday, preaching, sometimes being on-call for pastoral care emergencies, helping out Colton in the Advocacy Office (we would usually do outreach, passing out sandwiches to hungry people), and, in the springtime, conceiving of an awesome Lenten/Holy Week project called Writing the Dark Night with a friend of mine. This project came about through my attempts to create a St. Paul’s artists’ guild, or collective of artists. I started a blog and a Twitter feed and even held one meeting where I tried to structure it like a small group with a sort of urban monastic feel. That ended up really not working out. It was impossible to get people together, and indeed my studio classmates told me this kind of project might work better as something less regular or weekly – they suggested I try concrete events with clear timelines. After sitting on my butt and lamenting the problems of small groups (I’m not entirely convinced they work yet – I know some of them do but they don’t function the way they should ideally), I consulted a friend in the parish (also a seminarian) and we decided to just go ahead with our project: creation of graffiti-style Stations of the Cross which would be put up in the church, left there all through Lent and Holy Week, promoted through the websites and accompanied by explanatory sermons and Wednesday night “open houses” with harp music played by me. With the help of this brilliant artist the two of us and four other artists put together six stations and taped them to the walls of the parish. The response was dynamite – people loved them. I posted reflections on each one on our blog, and every Sunday at worship we live-tweeted questions inspired by the sermon. (I totally went on a rant about being on one’s cellphone in church to someone – this definitely came back to bite me in the butt). On Good Friday, we gathered together in the evening and, using a liturgy I had cobbled together from the reflections and the Book of Occasional Services, we actually walked these Stations of the Cross. I printed out ten bulletins because I hadn’t promoted it to the Diocese and expected only about five people. Twenty-one came to walk with us. It was a really profound experience. The project was topped off (I feel) by my friend and I reading St. John Chrysostom’s Easter homily as a dramatic dialogue together at the Easter Vigil. Finally, I hosted a retrospective two weeks later. This took a HUGE amount of work…and it was probably the coolest thing I’ve ever been a part of.

Discernment Group – This has not taken up nearly as much time as any of the other things, but it was something that raised my mental work a bit. For those not in the know, a discernment group is one of the first concrete steps toward ordination in this Diocese of the Anglican Church. It’s a very long process! It starts with a group of folks from your parish (preferably a mix of lay and ordained) having meetings with you for six to eight months. At the end of their time, they can give you a green, yellow, or red light to proceed. If you get a green light, you move on to what are called Examining Chaplains. You meet with them a few times and they assign you a mentor for the rest of the process. If they give you ANOTHER green light, you move onto ACPO, or the Advisory Committee on Postulants for Ordination. It’s usually a retreat held at Sorrento Centre on the shores of the gorgeous Shuswap Lake. There, people from different dioceses in the region seeking ordination meet and are grilled further, heh. If you make it through the grilling, they start to call you a “postulant,” and although this doesn’t mean unequivocally that you’ll be ordained, it does mean that the Diocese is seriously considering you. This is traditionally when most people are to start seminary. My process is a bit jumbled because I started with the intention of becoming a vocational deacon, and deacons have an entirely different process. However, no-one minds that my process has been different. During seminary, you stay in contact with your Bishop through sending him “Ember Day Letters” and meet with Examining Chaplains a few more times. If all goes well, by the time you graduate, you will have been assigned a place to go to work and eventually become an “ordinand.” Then you get to be ordained – first as a transitional deacon, and then as an honest-to-God priest. So after all that – I’m only at the discernment group part! I’ve got a long way to go…but when I met with my Bishop he told me that if all went according to plan and there was a place for me to work, I could be ordained by June 2014. I threw up in my mouth a little when he said that! Anyway, I should know if I’m moving onto the first round of Examining Chaplains by September at the latest, well in time to potentially make ACPO 2014.

Part-time Job! – A lot of people don’t know this, but throughout this whole time I was also working at my super-part-time harp teaching job! I work at Celtic Traditions Celtic Music School two afternoons a week. The hours obviously change depending on how many students I have, and I think it was actually a gift from God that this year was much quieter than years previous, with only about five or six students (there have been years where I’ve had ten). It did mean that I didn’t have much spending cash in my pocket, but somehow God still helped me pull through (with a lot of help from my amazing husband). It’s nowhere near as exhausting as the other endeavours, but it still represents a chunk of time and effort to arrange pieces and such. My students are great, but the job is really just a way for me to make money. Teaching harp is not a passion of mine. (Thankfully, teaching theology IS).

So that was my year, and I wasn’t joking about the seven months thing. There was literally never a day when something didn’t need to get done. I would have afternoons or evenings off, and that was about it. I became a bit of a hermit for a while – I’m an introvert and all that interaction (especially in the super disclosing environment of VST) exhausted me. Today I plan to do some laundry, maybe go out for a walk (or maybe not!) and make some jewerly, which is my latest creative hobby. I picked up some notions at Michael’s on Sunday because I knew that I would finally have time. I’ve got a big bucket of buttons (I love making jewelry out of buttons) and some beautiful beads.

It’s going to be a good day.

-Clarity

And at the end of yet another year (well, almost) I’m still alive and kicking!

I’m not quite finished yet; I have one more paper to write, which I’m taking way too long a break from right now. It’s not due until Monday and I spent hours today working in the library. When I came home I just couldn’t bear to look at it again. This time I colour-coded the notes I made and it’s going to make everything go a lot smoother!

Tomorrow I’ve got my Clinical Pastoral Education interview. I’m really nervous about it. I know the supervisor for the program is quite conservative, theologically, and…well, I’m the kid with the Tank Girl haircut. Don’t matter how nice I dress, it’s hard to avoid the cut. I’m in a weird position – I have no desire to mislead anyone, so I don’t want to wear a wig or anything, and wearing a hat to an interview just chafes my brain. At the same time, there’s a latent grown-up hiding in there that’s afraid of being laughed out of the room. The grown-up is doing battle with the person who demands to be fully accepted because of inner worth that was hard-earned. My hair does not change my capability and eligibility for this program. I also received explicit proof last Sunday that my hair has been a sign of hospitality and strength for at least one other person – a woman who had been afraid to come to church bald but no longer was after seeing me.

But I’m still trying to be accepted.

All I can do is represent myself well – and if I’m going to be myself I guess I might as well go all the way.

Everyone says I’m worrying too much and everything will go fine. I’m praying they’re right.

In other news, the Book Fairy at school left a couple of books outside the library and I grabbed one because it had “Coffin” written on the spine and I figured it was by William Sloane Coffin, who I really like.

The book was actually written by Henry Sloane Coffin, William’s uncle, and it’s called The Meaning of the Cross. The first couple of chapters got me a little nervous, because it seemed like it wanted to sell me on the redemptive sacrificial meaning of the Cross, and that’s something that can get me nervous. I’m really skeptical and twitchy about substitutionary atonement and anything that comes too close to it. I decided to give the book a whirl, though, on the off-chance that the writer would give me some new way of thinking about it that might make it work better for me. Just because I write off that interpretation of the Cross doesn’t mean other people do, and I’m unwilling to be too absolutist about an interpretation. Besides, I love to get creative about things in Christianity that bother me!

After about ten pages, though, I was hooked. I’ll write a proper review of it later when it’s not almost midnight and I’m not watching The Colbert Report as I type, heh. I’ve just been impressed at how the book is both deeply faithful and yet also very committed to a very merciful and social justice-oriented reading of the Cross (at least so far – I’m only 50 or so pages in but it’s a skinny little thing).

Anyway, I also happened to find this website which contains some more of his work, if you’re interested. :)

All right – I should really be getting to bed. I just wish I was tired.

-Clarity

Why why why WHY do I always end up staying up so late? I’ve been a night owl for years, but because my mother is a morning person I can at least move around and even have a conversation with someone before 9am. Just don’t expect me to remember it. That’ll be the first thing I tell anyone I work with.

I guess I was just thinking about today. It was the last Community Worship of the year, and my last as the sacristan. It’s someone else’s now – even if I wanted it, I couldn’t do it, because it’s a work study position and I’ll only be part time next year.

I’ve already registered! My last year has two fall classes with one Denominational course requirement (a little class that basically fills a weekend), and the spring term has two Denominational requirements (same deal). I’ll be taking Wendy Fletcher’s “Theology and Spirituality of Hospitality” and Public and Pastoral Leadership: Integration, which is the last big paper of an MDiv career at VST. I’m excited to get started on that – maybe even more excited than when I wrote my Major Exegesis. I get to write my heart, not just my brain.

Anyway, it was also the last worship service for this year’s VSGlee. We will meet again to sing for the VST Convocation – to sing this.

It’s weird to be gearing up for the last year. Of course my year isn’t even quite over yet. I still have to turn in three papers and have an “in-class interview” (as well as finish up some dangling coursework for that class). I’ll be glad when it’s over and I can get started on my next project. I did receive an email today from the CPE program I wanted to get into!!! They want to meet me for an interview! SHRIEK! It’s sort of silly – I’m a pretty good candidate for CPE and so shouldn’t be so nervous about being accepted, but that conditional thing always worries me a bit. I really REALLY hope I can do it this summer. Although I love academia and want to be a prof, my pastoral presence needs a shot in the arm. Something seminary does to me (and indeed to some others I’ve met) is make it almost impossible to talk about anyone but yourself in many situations! You’re so used to constant questions about who you are, what you believe, why you’re doing what you’re doing, and what your feelings and emotions mean in that given moment. I try to appear pastoral and I know I can, but I inevitably get wrapped up in my own BS and get sidetracked. Being a crisis counselor on the phone was helpful because there was no room for your own self to be there – you were all about the other person and their problems, and it was easy because they couldn’t even see you. I’m curious to see how my presence will change when I am in the same room with someone. I have done pastoral care before, but it wasn’t the same – one person was a lovely old lady who needed someone to tell stories to, and the other was someone who was a long-time friend and wanted to know all about school and family and everything else. Sometimes I would get her to talk about her own stuff, but it happened rarely. I think she liked distracting herself with my stuff so she wouldn’t get too focussed on her own. My most spiritual and holy moment with her, though, was as she lay dying in her bed in the hospice and I held her hand. She actually didn’t die until several days later, but she was mostly incoherent and I had no idea if she was quite aware who I was, or if she knew the whole time that I was in the room with her. At one point, she murmured, “I need to heal.”

In times like that, I find silence to be a good and faithful friend. I’m always on my soapbox about how silence is not appreciated in our culture. Other cultures or classes of people (like monks) will not speak unless what they have to say is really important. It seems like, increasingly, we speak more and more but about less and less important things. So few of us are brave enough to squeeze someone’s hand and say, “I need to heal.”

I miss my friend.

-Clarity