Mar 31 | “Lost and found,” (Sermon, March 31st 2019)

Now all the tax-collectors and sinners were coming near to listen to him. 2And the Pharisees and the scribes were grumbling and saying, ‘This fellow welcomes sinners and eats with them.’

So he told them this parable:

‘There was a man who had two sons. 12The younger of them said to his father, “Father, give me the share of the property that will belong to me.†So he divided his property between them. 13A few days later the younger son gathered all he had and travelled to a distant country, and there he squandered his property in dissolute living. 14When he had spent everything, a severe famine took place throughout that country, and he began to be in need. 15So he went and hired himself out to one of the citizens of that country, who sent him to his fields to feed the pigs. 16He would gladly have filled himself with the pods that the pigs were eating; and no one gave him anything. 17But when he came to himself he said, “How many of my father’s hired hands have bread enough and to spare, but here I am dying of hunger! 18I will get up and go to my father, and I will say to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; 19I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me like one of your hired hands.’ †20So he set off and went to his father. But while he was still far off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion; he ran and put his arms around him and kissed him. 21Then the son said to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son.†22But the father said to his slaves, “Quickly, bring out a robe—the best one—and put it on him; put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. 23And get the fatted calf and kill it, and let us eat and celebrate; 24for this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!†And they began to celebrate.

25 ‘Now his elder son was in the field; and when he came and approached the house, he heard music and dancing. 26He called one of the slaves and asked what was going on. 27He replied, “Your brother has come, and your father has killed the fatted calf, because he has got him back safe and sound.†28Then he became angry and refused to go in. His father came out and began to plead with him. 29But he answered his father, “Listen! For all these years I have been working like a slave for you, and I have never disobeyed your command; yet you have never given me even a young goat so that I might celebrate with my friends. 30But when this son of yours came back, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fatted calf for him!†31Then the father said to him, “Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours. 32But we had to celebrate and rejoice, because this brother of yours was dead and has come to life; he was lost and has been found.†’

Luke 15:1-3, 11b-32

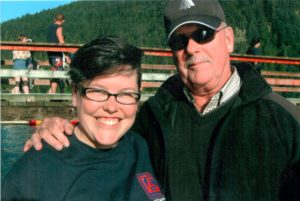

Five years ago, on a Wednesday in early April, my father got up, made coffee, went downstairs to warm up his wife’s car, and dropped dead of a massive heart attack. He was sixty-four years old.

One of the reasons I love St. Margaret’s so much is that we use such expansive imagery for God. We don’t solely rely on “Father.†I appreciate it because I had a complicated relationship with my father. I don’t get much of a sense of warmth or intimacy when I imagine God as father. My mum and I are like two peas in a pod, and my dad was different. He was a quiet, self-contained person. He always seemed trustworthy but distant, deeply grounded but a little apart. After my parents split, I always felt he had a life quite separate from mine. I felt like everyone else knew him better than me, like I was being denied something that he gave freely to others, and I didn’t know why.

In his death, the valley that had always existed between us became an impassable abyss.

I can’t square those feelings with the ones I have for God. With God, even in the times where She felt distant, I have always felt invited to pursue, to deepen the relationship, to come running home.

Last week’s passage was from the beginning of Chapter 13 in the Gospel of Luke. Strangely, the week before that we heard from later in Chapter 13, the passage about Herod the fox. Now here we are in Chapter 15. This is weird, and it leaves a lot of good stuff out by skipping Chapter 14! Let’s look at what’s happened between last week and this week.

Jesus, the rabble-rouser, is invited to dinner at a Pharisee’s house. How magnanimous. Prove your enlightenment by inviting the hayseed preacher to possibly make a fool of himself. Except, of course, Jesus doesn’t. He just makes it super awkward by criticizing the seating arrangement and telling a parable about a rich dude who invites poor people to his banquet when his friends won’t come.

Jesus then goes straight from the fancy party to the crowd of poor folks who are following him – so pointed! Don’t you love it? – and tells them to count the cost carefully before following him, because they’ll need to give up everything.

This annoys the rich folks. They mumble, “He welcomes and sinners and eats with them! The only kind of people who’d follow this train wreck are people who have nothing to lose!â€

That prompts Jesus to tell three parables about lost things – a sheep, a coin, and a son.

In the parables, each lost thing is found again, to great celebration. The story of the prodigal son is the one that has the most detailed account of celebration. This makes sense – a lost person is more dramatic and poignant that a lost coin or sheep. But this story is also the only one which includes the perspective of someone who isn’t happy about the finding.

The woman who finds her coin and the shepherd who finds his sheep invite the neighbours to rejoice with them, and no-one seems to object. But the doting father has a son who never strayed, who has worked hard without recognition, or at least he thinks so. He lashes out at the father, calling his own brother “this son of yours.â€

Jesus tells this story to remind the Pharisees, the ultra-faithful, that they should not resent God for welcoming heretics and heathens.

There’s also another layer here. In all three stories, the lost things symbolize a secure future. Sheep are a part of one’s holdings. The coins are, in Greek, drachmas, about a day’s wage. These are safety nets for lean times, a part of the person’s estate.

A lost son is likewise a caregiver and a legacy.

This makes the anger of the older son even more understandable. Isn’t he a legacy too? His question might be the same question we have: You already have ninety-nine other sheep! You already have nine other coins! You already have an heir! Why spent all this energy on the lost one?

It’s not that the older son is wrong to be angry. It’s more than he’s missed the point. Everything that belongs to his father is his as well. He already has a place at the table and in the legacy. He may have a right to be annoyed at the waste of a good fatted calf for his loser brother…but the assumption is that he will join in the feast, because he is part of the family that is now whole again.

Like the other son, he suddenly acts as though he is a worker who deserves payment, rather than a son with a seat at the table.

Why would he exclude himself?

Like a good father, God is invested in us. It doesn’t matter how many sheep are in God’s fold, or how many coins are in God’s purse, or how many children work hard at home while the lost ones make their way home hungry and smelling of pigs. Look at the almost childlike delight of the shepherd and the woman, so happy they’ve found sheep and coin that they invite the neighbours over for a party! God wants us. God runs out to meet us, robes to the knee – at our worst, ignoring all the excuses for why we’re late or unworthy, and at our best, faithful and hard-working yet resentful of the grace extended to others.

I think we’ve all been in both places. We know what it feels like to be lost and welcomed home, and we know what it feels like to suddenly feel ourselves grow up faster than we would like, and how much it can hurt, whether it happened in the pig pen looking for redemption or outside the door of the banquet looking for maturity.

A little over a week after my father died, it was Good Friday, and I was at the Cathedral. I saw someone I didn’t expect: Christopher Lind, former executive director of Sorrento Centre. Only a few months into his employment, he was diagnosed with a terminal brain tumour. He had not yet gone for surgery, and was staying at VGH.

I had only met him a couple of times, but I liked him, so I went over to talk to him.

I told him about my dad. Then I told him about the trip I was to take to El Salvador that summer.

I also told him something I hadn’t really shared with other people: my dad hadn’t wanted me to go.

When I told Dad about the trip, he told me that he knew I was an adult and could do what I pleased, but he wished I wouldn’t go, because he was worried about me.

I don’t think we had ever had a conversation like that before.

Chris smiled and said, “Sometimes that’s the only way fathers know how to say I love you.â€

Then, abruptly, he burst into tears.

Of course I did too, and asked if I could give him a hug.

“Please?†he replied.

I can’t imagine my dad running to me like the father of the prodigal. But he never did get a chance to see me come home safe from El Salvador. Maybe he would have surprised me.

It’s almost second nature to imagine God being this way.

And indeed, for a moment on Good Friday, standing next to me at the abyss, was someone who kind of reminded me of the one I had lost, contemplating his own abyss, his own fear, his own unexpected return to a father who always comes running, who always rejoices at our return, and who always welcomes us home no matter how angry or how sad or how humiliated we are.

Did he find me, or did I find him?

Doesn’t matter. We were both found.