May 01 | The Face of the Word: The Christ-Icon Yesterday and Today

Hundreds of years ago, a face was painted on a board. It is highly unlikely that the artist could have guessed I would be contemplating it as a young woman in the twenty-first century not once, but twice, in the hopes of copying it as a novice iconographer. My first attempt, done during a very stressful period of my life, was both beautiful and heartbreaking. The icon itself, though it has stayed the same year after year, has changed so much in my own eyes.

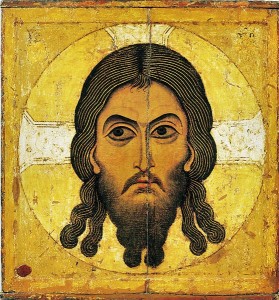

The icon is the Holy Mandylion. Christ’s dark face stares up from a circle of gold. My first time was done in acrylic on a very simple canvas, layered over with clear varnish. It was consecrated on Palm Sunday, 2008. The process had been amazing for me, and so during the summer of 2011 I undertook an icon class to paint the beloved face again. Before we actually laid our natural pigments to the board, however, we participated in a group meditation on our blank boards. What came to me was so profound I sought to look deeper.

This paper seeks to understand the significance of the meditation I had on the blank board, using both the tools of my own mind, and those provided to me by a study of iconography and its history.

I began with the injunction to pray for those who had upset me and forgive them. The professor also encouraged us to keep in mind creation, and the beautiful stories of Genesis. The meditation came to me very quickly, and I have transcribed it as best I could here.

I feel immediately connected. I am filled with light, and everyone who has ever angered me is lifted up. I embrace them.

I come to the board but it is not Genesis. It is John’s Prologue: In the beginning was the Word. The tiny bumps on the board are like stars in a clear sky. It is the darkness which cannot be overcome. He is my light. I pour life into this board: blood of light. I bleed life into the board: God tears at my heart and dances me into kenosis.

The board seems to move. I find I want to close my eyes. I’m not a very visual person when I pray…but I want to be. I am always overstimulated by images – they have so much power over me. If I can meet God with eyes open and not be burned away I may understand that…I don’t know. How can white become gold? How can light be more than light? Light is light but it is infused.

At this point in the meditation I tried to turn my focus onto the print we were given of the Holy Face. After the pure whiteness of the board, however, the darkness, richness and deep colours of the Face were almost unbearable. I was reminded of Moses and his veil as he came down from the mountain. I decided to put the board over parts of the Face to help me focus better.

I put the board over his lower face. Now I can only see his eyes. One looks into me, the other elsewhere. One is human, the other is more, yet both are both. His eye meeting mine is the eye of God that shone from one human face to another, and the eye that looks up is a human eye that knows fullness of being – the human as God intended, the human in perfect union.

I move the board to the right side of his face. His eye looks into me. There is only a tiny pinpoint of light in it. His human eye looks like the beginning of all things. His eye knows the all, and everything in me.

His left eye looks upward with less softness. There is determination, as though listening. It is commanding. From down here where I sit on the floor, he looks up at some of my classmates. He is looking at The Other, the one he served and the one I must serve. There is no choice. This way is the way of God. Not necessarily “Christianity†per se, but God’s whole way of being: service. This way is the only way to union. We can’t meet him halfway if we want to be true followers. This is amazing, because his human eye looks into me and knows my faults, knows my humanity. We will always be struggling between the two: who we are and what we need to become. He who was both is here to guide…and he understands. Something else I see that is truly beautiful arises. Just as his human eye has that tiny spark of divinity in it, the “God side†of his face has lips that are full and red. These lips seem ready to offer me a kiss of peace: Peace be with you.

Thank you, Lord. I believe.

My Own Interpretation

Despite the fact that I ruled out Genesis in the meditation, on further reflection I do find pieces of it here. The sky was dark and full of stars but ultimately still empty, devoid of moon or any reflection. It is a pregnant sky, waiting to burst from its potential.

The questions about light becoming gold and how light can be more than light seem very primal to me. The real question seems to be, “How can nothing become everything?†It also reminded me of the Incarnation: how can the pure light of one human life – Mary – suddenly become infused with gold, the holiness of God? How does this one beautiful creature suddenly become what the Orthodox call Theotokos?

Not being able to look at the Face after the whiteness of the board was very significant for me. It really did feel like staring into the Transfiguration, or trying to look into the upper clouds on Sinai. It also reminded me of Genesis, that humans were the last creatures to lay eyes on God.

I had heard from an unremembered source that the somewhat mismatched eyes of Christ in many icons are done deliberately, precisely to illustrate his dual nature. My mind clearly fixed on that and contemplated the presence of the Word in a human life. In fact, the word I focussed on during the course of the meditation was “Wordâ€, although sometimes in my mind I settled on the gorgeous Logos.

This meditation for me was incredibly full, and on its own it helped me greatly, since there was an imperative within it – that of service. I was curious, however, in the fact that I had begun to focus on John’s Prologue. The passage’s connection to the icon did not seem immediately apparent at first, and so I decided to consult some other sources to see what I could learn from other, more adept and educated minds than my own.

Further Study

Seeking God through the created image is something that has walked alongside Christianity for a very long time. We can never be entirely sure how long, though, since although we are aware of Christians producing art by the 3rd century, it is difficult to recognize art that could be called “Christian†before then.[1] It’s also uncertain as to whether or not the early Christian church was supportive of Christian art. Bursts of iconoclasm occurred in the eighth and ninth centuries, as well as attempts to ban images altogether. Despite the uncertainty, we know that Christian art began to emerge, and early in its inception it was much like contemporary Roman art.[2] The main difference is that Christian art, while keeping the forms of Roman art, began to develop biblical subject matter in a way that had not been seen before. Robert Cormack observes that, “[T]he discussion about early Christian art has been one about the ways in which art can change its meanings more easily than its forms.â€[3]

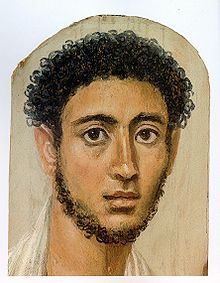

Examples of the medium in which icons first came into being – panels painted in tempera on a textile with gesso as a base – can be found at Fayyum in Egypt in Roman cemeteries. The paintings, some of them triptychs with gods or goddesses surrounding a face, were thought to be portraits of the dead that had been mummified.[4] The close proximity of these paintings to the monastery of St. Catherine at Sinai suggests to Cormack that “in developing art in the service of the new faith, Christians had in their sights an effective medium already in religious use.â€[5]

In Christoph Schonborn’s God’s Human Face: The Christ-Icon, Schonborn observes in the Fayyum paintings “a change influenced…by the Jewish-Christian view of man.â€[6] Looking at a third century mummy portrait as provided by the book, I am struck by the similarities to the Holy Face. This face seems lit from within by a deep rosy glow, and the eyes are very large and full of life. The nose is long and thin, the lips full and potent but the mouth small in relation to the rest of the face. These large eyes are a way to demonstrate a deep spirituality – an “inner seeingâ€[7] – while the small mouth demonstrates that the deeply enlightened have no need for dialogue. Remembering the writing of my first icon, I was attentive to the points of light around the face and noticed they were similar if not the same to where they had been on the Holy Face: several around the eyes and a few at the bridge and the tip of the nose. This contributes to the realistic aspects of the portrait, but also hints at an almost chakraÂ-esque view of the human facial form. Points of light become points of energy concentrated inward and yet radiating outward.

The use of these contemporary commonplace mediums to communicate the message of the divine in human form seemed to me to echo many of the basic elements in the early Christian community. The most obvious one would be the theme of the ordinary being transformed. An ordinary home is consecrated during the agape meal. An undesirable such as a leper is welcomed into a loving community. A form of painting becomes a “window looking out upon eternity.â€[8] None of these things are completely turned into new things. The house remains a house, the leper remains a leper, and the painting remains a painting. They are deeply changed within, however. The action and intention of those who perform the change infuses these ordinary things with light. These early icons were still religious paintings of those who had died or gone into the next world, but they were not simply a record to help the dead find themselves again. Instead they were kept and treasured as links to those they represented, kissed and wept over, loved and cherished. Intriguingly, Cormack also notes that “The reliance of the people on icons as a window to heaven was gradually seen as a subversive threat to the authority and control of the state.â€[9] Here transformation becomes infused with the light of empowerment.

The exploration of the icon’s origins provided me with a fascinating window into the history of the Face as it looked to me during my meditation. The transformation of the simple panel paintings into something that helped believers into a new way of seeing seemed to call out to me to continue to transform my own life through faith. However, I still did not understand exactly why the Face affected me quite the way it did. I still wanted to know how the painting of our Lord’s Face as it was presented could bring me closer to God. To answer this question, I turned to Schonborn again and explored his summary of the Christological arguments that helped to develop a new way of looking at personhood, which had implications both for faith and for human interaction.

Schonborn presented through Gregory of Nyssa a great answer for why I could not fully look at the Face. While explaining Gregory’s exposition on the nature and essence of the divine persons, Schonborn finds a template for the development of a theology of the icon:

“[T]he contemplation of the countenance of the Son imprints in our heart the seal of the Person of the Father. Because he is the Son of the Father, the Father becomes visible in him.â€[10]

Gregory of Nyssa uses the image of a mirror to explain how we might understand the Son’s relationship to the Father: that the image in a mirror is the same as the original and yet is not the original. Since the image is the same it can be honoured but not worshipped per se – a way of describing how many use icons in worship.

I was endlessly curious as to why I turned from an immediate Genesis interpretation to a Johannine one. I found that John’s Prologue was an oft-cited source for many of these early Christological arguments, and reflected on the choice of the writer of John to refer to the Word (Logos) becoming flesh (sarx) rather than man (anthropos). The writer of John speaks rhapsodically of the whole universe being alight with Logos/Christ. This to me affirms a tenet of iconography which states that everything has been created by God, and that it therefore must be viewed as good by the believer/writer, that it participates in goodness.[11] Iconographer Matthia Langone notes that the icon “points to the reality of the Incarnation, the goodness of creation and the dignity of the human person.â€[12] The church father Irenaeus spoke of creation revealing the one who formed it. For Cyril of Alexandria, “the flesh [was] not an ‘extrinsic cover’ but belongs to the very identity of the Logos.â€[13] In defending the use of icons during what Schonborn refers to as “the gathering iconoclastic stormâ€, the eighth century saint Patriarch Germanus also refers to John:

“Of the invisible deity we make neither a likeness nor any other form. For even the supreme choirs of the holy angels do not fully know or fathom God. But then the only-begotten Son, who dwells in the bosom of the Father (cf. Jn 1:18), desiring to free his own creature from the sentence of death, mercifully deigned…to become man. … For this reason we depict his human likeness in an image, the way he looked as man and in the flesh, and not as he is in his ineffable and invisible divinity.â€[14]

For Schonborn, all iconophilic arguments could be summed up as such: “[T]he Incarnation means that the Eternal Word has assumed a visible likeness.â€[15]

I was delighted in the soul-resonance I felt with these early church fathers and the use of John. Christological arguments aside, I found another excellent source for reflection in Henri Nouwen’s soul-stirring Behold the Beauty of the Lord. Deeply moved by his experiences praying with Russian icons, Nouwen reaches zeniths of beauty in prayer that speak to my heart. His meditation on the Saviour of Zvenigorod struck chords in my mind:

“The eyes…are the eyes of the Son of Man and Son of God described in the Book of Revelation…He is the light of the first day when God spoke the light, divided it from the darkness, and saw that it was good. (Gen. 1:3) He is also the light of the new day shining in the dark, a light that darkness could not overpower. (Jn. 1:5)â€[16]

For Nouwen, this was a deep celebration of the Incarnation: “We can see God and live! As we try to fix our eyes on the eyes of Jesus we know that we are seeing the eyes of God.â€[17]

Conclusion

After further exploration I have come back to my own little room, in which one candle burns for Christ all day and all night. I suppose, though, that one thing has changed: this icon now hangs within. As Nouwen observes, “Icons are painted to lead us into the inner room of prayer and bring us close to the heart of God.â€[18] As iconographer Matthia Langone observes in an interview, “[T]he icon…is like a door one leaves behind as one crosses the threshold into another dimension of reality.â€[19]

Exploration of the theology of icons has brought me into a beautifully close relationship with the divine, for I feel that I have not missed out, by virtue of being born two thousand years too late, in seeing the face of the Lord. Because he came among us, he will forever be one of us, and he will forever be before us should we choose to look. In John’s Prologue we are gifted with the beauty of his primacy, and with John’s faith and comfort in knowing that his Lord’s life was lived with complete intentionality from start to finish. Indeed, when I looked into that face, I could not believe anything otherwise! There from one face burn the two perfect eyes of my Beloved: the one that looks into me and sees me for what I am, and the one that looks beyond me and sees all of us for what we could be if we only follow. This is the nature of God: to be known by us, and to call us to honour our creation (all creation), and to strive for our intimacy with the one who made us, who came among us, and who burns within us.

Amen. I believe…and I see.

Bibliography

Â

Behold the Beauty of the Lord: Praying with Icons, Henri J.M. Nouwen

Ave Maria Press, Notre Dame, Indiana. 1987/2007 (revised edition)

God’s Human Face: The Christ-Icon, Christoph Schonborn

Ignatius Press, San Francisco. 1994

From the German translation, Die Christus-Ikone. Eine theologische Hinfuhrung

(Novalis Verlag, Schaffhausen, Germany, 1984)

Originally published as L’Icone du Christ. Fondements theologiques elabores entre le Ier et le IIer Concile de Nicee (325-787 AD)

(Editions Universitaires, 2nd ed. Fribourg, 1976, 1978)

Painting the Soul : Icons, Death masks, and Shrouds, Robert Cormack

Reaktion Books Ltd., London, UK. 1997

[1] Painting the Soul, (Robert Cormack), 64

[2] Ibid., 65

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., 67

[5] Ibid., 65

[6] God’s Human Face, 24

[7] “The Way of the Icon†classroom notes, July 11th/2011

[8] Behold the Beauty of the Lord, Henri Nouwen, 24

[9] Painting the Soul, 19

[10] God’s Human Face, 31 (italics orig.)

[11] “The Way of the Icon†classroom notes, July 11/2011

[12] “The Way of the Iconâ€, 2, interview with Matthia Langone conducted by Karen Walker, June 2004 (article reprinted with permission from the Thomas Aquinas College Alumni Newsletter)

[13] God’s Human Face, 81

[14] Ibid., 181

[15] Ibid., 185

[16] Behold the Beauty of the Lord, 81

[17] Ibid., 80

[18] Ibid., 23

[19] “The Way of the Iconâ€, Walker/Langone, 7