Apr 06 | Sand and Bone Track #5 – Ubi Caritas

Mar 31 | “Lost and found,” (Sermon, March 31st 2019)

Now all the tax-collectors and sinners were coming near to listen to him. 2And the Pharisees and the scribes were grumbling and saying, ‘This fellow welcomes sinners and eats with them.’

So he told them this parable:

‘There was a man who had two sons. 12The younger of them said to his father, “Father, give me the share of the property that will belong to me.†So he divided his property between them. 13A few days later the younger son gathered all he had and travelled to a distant country, and there he squandered his property in dissolute living. 14When he had spent everything, a severe famine took place throughout that country, and he began to be in need. 15So he went and hired himself out to one of the citizens of that country, who sent him to his fields to feed the pigs. 16He would gladly have filled himself with the pods that the pigs were eating; and no one gave him anything. 17But when he came to himself he said, “How many of my father’s hired hands have bread enough and to spare, but here I am dying of hunger! 18I will get up and go to my father, and I will say to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; 19I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me like one of your hired hands.’ †20So he set off and went to his father. But while he was still far off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion; he ran and put his arms around him and kissed him. 21Then the son said to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son.†22But the father said to his slaves, “Quickly, bring out a robe—the best one—and put it on him; put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. 23And get the fatted calf and kill it, and let us eat and celebrate; 24for this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!†And they began to celebrate.

25 ‘Now his elder son was in the field; and when he came and approached the house, he heard music and dancing. 26He called one of the slaves and asked what was going on. 27He replied, “Your brother has come, and your father has killed the fatted calf, because he has got him back safe and sound.†28Then he became angry and refused to go in. His father came out and began to plead with him. 29But he answered his father, “Listen! For all these years I have been working like a slave for you, and I have never disobeyed your command; yet you have never given me even a young goat so that I might celebrate with my friends. 30But when this son of yours came back, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fatted calf for him!†31Then the father said to him, “Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours. 32But we had to celebrate and rejoice, because this brother of yours was dead and has come to life; he was lost and has been found.†’

Luke 15:1-3, 11b-32

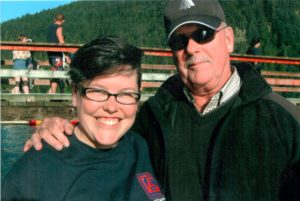

Five years ago, on a Wednesday in early April, my father got up, made coffee, went downstairs to warm up his wife’s car, and dropped dead of a massive heart attack. He was sixty-four years old.

One of the reasons I love St. Margaret’s so much is that we use such expansive imagery for God. We don’t solely rely on “Father.†I appreciate it because I had a complicated relationship with my father. I don’t get much of a sense of warmth or intimacy when I imagine God as father. My mum and I are like two peas in a pod, and my dad was different. He was a quiet, self-contained person. He always seemed trustworthy but distant, deeply grounded but a little apart. After my parents split, I always felt he had a life quite separate from mine. I felt like everyone else knew him better than me, like I was being denied something that he gave freely to others, and I didn’t know why.

In his death, the valley that had always existed between us became an impassable abyss.

I can’t square those feelings with the ones I have for God. With God, even in the times where She felt distant, I have always felt invited to pursue, to deepen the relationship, to come running home.

Last week’s passage was from the beginning of Chapter 13 in the Gospel of Luke. Strangely, the week before that we heard from later in Chapter 13, the passage about Herod the fox. Now here we are in Chapter 15. This is weird, and it leaves a lot of good stuff out by skipping Chapter 14! Let’s look at what’s happened between last week and this week.

Jesus, the rabble-rouser, is invited to dinner at a Pharisee’s house. How magnanimous. Prove your enlightenment by inviting the hayseed preacher to possibly make a fool of himself. Except, of course, Jesus doesn’t. He just makes it super awkward by criticizing the seating arrangement and telling a parable about a rich dude who invites poor people to his banquet when his friends won’t come.

Jesus then goes straight from the fancy party to the crowd of poor folks who are following him – so pointed! Don’t you love it? – and tells them to count the cost carefully before following him, because they’ll need to give up everything.

This annoys the rich folks. They mumble, “He welcomes and sinners and eats with them! The only kind of people who’d follow this train wreck are people who have nothing to lose!â€

That prompts Jesus to tell three parables about lost things – a sheep, a coin, and a son.

In the parables, each lost thing is found again, to great celebration. The story of the prodigal son is the one that has the most detailed account of celebration. This makes sense – a lost person is more dramatic and poignant that a lost coin or sheep. But this story is also the only one which includes the perspective of someone who isn’t happy about the finding.

The woman who finds her coin and the shepherd who finds his sheep invite the neighbours to rejoice with them, and no-one seems to object. But the doting father has a son who never strayed, who has worked hard without recognition, or at least he thinks so. He lashes out at the father, calling his own brother “this son of yours.â€

Jesus tells this story to remind the Pharisees, the ultra-faithful, that they should not resent God for welcoming heretics and heathens.

There’s also another layer here. In all three stories, the lost things symbolize a secure future. Sheep are a part of one’s holdings. The coins are, in Greek, drachmas, about a day’s wage. These are safety nets for lean times, a part of the person’s estate.

A lost son is likewise a caregiver and a legacy.

This makes the anger of the older son even more understandable. Isn’t he a legacy too? His question might be the same question we have: You already have ninety-nine other sheep! You already have nine other coins! You already have an heir! Why spent all this energy on the lost one?

It’s not that the older son is wrong to be angry. It’s more than he’s missed the point. Everything that belongs to his father is his as well. He already has a place at the table and in the legacy. He may have a right to be annoyed at the waste of a good fatted calf for his loser brother…but the assumption is that he will join in the feast, because he is part of the family that is now whole again.

Like the other son, he suddenly acts as though he is a worker who deserves payment, rather than a son with a seat at the table.

Why would he exclude himself?

Like a good father, God is invested in us. It doesn’t matter how many sheep are in God’s fold, or how many coins are in God’s purse, or how many children work hard at home while the lost ones make their way home hungry and smelling of pigs. Look at the almost childlike delight of the shepherd and the woman, so happy they’ve found sheep and coin that they invite the neighbours over for a party! God wants us. God runs out to meet us, robes to the knee – at our worst, ignoring all the excuses for why we’re late or unworthy, and at our best, faithful and hard-working yet resentful of the grace extended to others.

I think we’ve all been in both places. We know what it feels like to be lost and welcomed home, and we know what it feels like to suddenly feel ourselves grow up faster than we would like, and how much it can hurt, whether it happened in the pig pen looking for redemption or outside the door of the banquet looking for maturity.

A little over a week after my father died, it was Good Friday, and I was at the Cathedral. I saw someone I didn’t expect: Christopher Lind, former executive director of Sorrento Centre. Only a few months into his employment, he was diagnosed with a terminal brain tumour. He had not yet gone for surgery, and was staying at VGH.

I had only met him a couple of times, but I liked him, so I went over to talk to him.

I told him about my dad. Then I told him about the trip I was to take to El Salvador that summer.

I also told him something I hadn’t really shared with other people: my dad hadn’t wanted me to go.

When I told Dad about the trip, he told me that he knew I was an adult and could do what I pleased, but he wished I wouldn’t go, because he was worried about me.

I don’t think we had ever had a conversation like that before.

Chris smiled and said, “Sometimes that’s the only way fathers know how to say I love you.â€

Then, abruptly, he burst into tears.

Of course I did too, and asked if I could give him a hug.

“Please?†he replied.

I can’t imagine my dad running to me like the father of the prodigal. But he never did get a chance to see me come home safe from El Salvador. Maybe he would have surprised me.

It’s almost second nature to imagine God being this way.

And indeed, for a moment on Good Friday, standing next to me at the abyss, was someone who kind of reminded me of the one I had lost, contemplating his own abyss, his own fear, his own unexpected return to a father who always comes running, who always rejoices at our return, and who always welcomes us home no matter how angry or how sad or how humiliated we are.

Did he find me, or did I find him?

Doesn’t matter. We were both found.

Mar 31 | Sand and Bone Track #4 – Magdalene

Mar 23 | Sand and Bone Track #3 – Longinus

Mar 07 | Sand and Bone Track #1 – Deborah’s Song

Welcome to Sand and Bone, 2019’s Lenten devotional project!

Mar 06 | “Coming out of the [prayer] closet,” (Ash Wednesday Sermon, March 6th 2019)

It’s always fascinating to preach on Ash Wednesday in a queer affirming church.

Why?

Because I am constantly reminded of the King James Version of the passage from Matthew, which reads at verse 6: “But thou, when thou prayest, enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut the door, pray to thy Father which is in secret; and thy Father who seest in secret shall reward thee openly.â€

Man, is there ever a good time to enter into thy closet once you’ve come out of it?

Now, don’t get me wrong. For some of our friends around the world and even here at home, the closet is a safer place to be than outside of it, at least for the moment. But it’s no-one’s ideal. And in the world we’re living in today, if it’s safe to come out, we should – not just for our own health, but to shame the bigots with the blazing light of courage. Representation ain’t easy to come by. Come out in all your glory.

Likewise, these days the progressive church should come out of the closet. We should celebrate its power to comfort those who seek refuge in its message of unconditional love for all God’s children. We shouldn’t be shy in who we are and who we serve. Progressive Christians do tend to feel it’s gauche to ask, “Do you know Jesus?†to everyone who passes by, and with good reason. We don’t have to adopt every tool our more conservative siblings employ. But in the time we’re living in, isn’t it be better to cry aloud that God has come among us and is making all things new?

And so is now, in the hurting and fractured and angry world we live in, the best time to be mucking about in the closet?

Well, the passage we just heard from Matthew doesn’t occur in a vacuum. It’s balanced not only with the out-and-proud call to justice of the prophet Isaiah, who chooses the fast of liberation, but with the memory of what came before in Matthew’s Gospel.

In Chapter 5, Jesus tells us to repudiate the norms of the world we live in. In the Beatitudes, he tells us we live in an upside-down world where the poor in spirit, the lowly, and the meek and mild are the ones who will inherit God’s kingdom. He tells us that we should be salt and light, impossible to hide, heroes of our neighbours, out and proud. He tells us that he is not here to abolish any of the laws but to fulfill them, and we should therefore be more righteous, more kind, more radical than any have yet been. He constantly repeats the refrain, “You have heard that it was said… But I say…†The law says do not murder. I say do not even be angry with each other. The law says do not swear falsely. I say do not swear at all. The law says “An eye for an eye.†I say “Turn the other cheek.†In all things, he says, we are to shame the other with our peaceful nonviolent resistance.

Then he says, “Oh, but do it quietly.â€

Is that even possible?!

How can we live out loud in the closet?

Of course it’s likely Jesus is employing hyperbole here. But let’s go a little deeper. Let’s ask ourselves what this could mean in the season of Lent.

In the season of Lent, we strip away our desires and illusions and accretions to get at our spiritual core. We dive deep to harvest pearls, those strange treasures that form and harden around the grit of imperfection and mortality, and offer them back to God.

On this particular night, we admit our needs to the God who made us this way. We admit our dependence and our confusion. We admit our evanescence and our fragility. We admit the impossibility of the task we have been given – living loud but little lives – and together lean on each other in our vulnerability. We accept that our work can never be done in one lifetime, and that’s okay.

In a sense, we do get into the closet in the season of Lent: not because it’s a good or a holy place, but because it reminds us that it exists only to be shattered in the light of Easter. The closet is really just a symbol, maybe a microcosm, of our own limitations, the ones imposed upon us by our beautiful broken world and the ones we impose upon ourselves out of fear and anxiety. It’s not easy to live out loud.

But we shouldn’t despair, for in a sense God too entered the closet, a closet of earthly flesh, in Jesus Christ. And despite all his best efforts to come out, to tell his truth – that he was the Messiah despite his frailty and utter ordinariness – humanity just stood outside the doors and wondered what all the racket was about. The disciples only recognized the truth when God blew the doors right off their hinges one Sunday morning… Ah, but we’re not at that point in the story yet.

The prophet Isaiah tells us to live out loud by throwing ourselves into self-sacrificing love, that this will be our liberation. But Matthew reminds us that we do not do this work solely for our own glory. It is truly God’s joy to see us burst forth from the confines of the closet. How much more will she rejoice if we respond to our freedom by running off to yank open other closet doors? Your liberation is only the first step. The next step is sharing your freedom with others who are reaching for it. In coming out we discover that we are not alone. Once we have filled our cup with strength, we have power to re-enter without fear, for when we open the doors, we discover that we are no longer alone: we meet the Beloved within! “Seven minutes in heaven†indeed!

This is why we mark Ash Wednesday. We can only celebrate the unbound freedom of resurrection when we are willing to embrace the dark and stuffy confines of death. When we remember the closet, remember times when we were fighting to stay alive like a butterfly in a jar, we are given the power to liberate the ones who are still trapped, to blow those doors right off their hinges as God once did and as God continues to do.

And closets are not just a place to hide, of course. Closets are for storing treasures with which to adorn ourselves. Some of these treasures are bright and colourful, like integrity and grit, and some are small and delicate but all the more precious, like vulnerability and fear.

All of these things were woven into the fabric of God’s robes of flesh. And God looked fabulous in that ensemble. So too do we embody the beauty of a God who went into the closet not to hide and wither there, but to gather up a rainbow of treasures to share with the world, to invite others to share their brightest and best.

This evening, we are gathered together in this closet, this little church, admitting that our beautiful bodies are especially beautiful because they don’t last forever, and our beautiful contradictions are beautiful because sometimes despite it all we choose compassion and love and kindness. We’re embracing our finitude with a small sign here, where everyone can see it.

And then, we’re coming out.

We’re coming out into a world that rages against death and scorns the aged. We’re coming out into a world that trumpets brute strength over emotional vulnerability. We’re coming out into a world that increasingly asks if love is possible.

We’re coming out, and no-one said it was easy – but we’re together, and we look fabulous.

Jan 27 | “Coming home matters,” (Sermon, January 27th 2019)

“Then Jesus, filled with the power of the Spirit, returned to Galilee, and a report about him spread through all the surrounding country. He began to teach in their synagogues and was praised by everyone.

When he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up, he went to the synagogue on the sabbath day, as was his custom. He stood up to read, and the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was given to him. He unrolled the scroll and found the place where it was written:

‘The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.’

And he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant, and sat down. The eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him. Then he began to say to them, ‘Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.’”Luke 4:14-21

In an episode of the podcast Revisionist History, host Malcolm Gladwell explores the story of Dr. Ivan Frantz, who conducted a massive experiment on heart health. Most of the episode chronicles the strange story of what happened to the results of that test, but some of it also explores the relationships between fathers and sons as Gladwell interviews Dr. Frantz’s son, and reflects on the recent death of his own father.

After a call out of the blue from an interested Christopher Ramsden, whom one article described as “the Indiana Jones of biology,†Dr. Frantz’s son Robert, also a doctor, is tasked with poking through his father’s basement looking for the results of this massive study, and he eventually finds them in a mouldering box. What he discovers is that the results contradicted his father’s own deeply held convictions about their subject. Ramsden, upon learning this, is careful to ask Robert for permission to publish these studies, since they could be seen to be damaging to his father’s legacy of belief. Robert explains that the results should be published, because his father was more interested in the truth than in being right.

Gladwell concludes, “We don’t honour our parents by upholding beliefs, but principles.â€

I think we often conflate the two, but the more I think about it, the more I do think they’re different. I think we’re more likely to see our beliefs change over time than our principles.

In our reading from the Book of Nehemiah, the priest Ezra welcomes the exiled people of Judah back by reading the Book of the Law. Overcome with emotion and maybe fear, they weep as they hear the words sacred to their ancestral faith. They have come home and can now keep the law as they once did. Ezra tells them that this is a joyous day. Although they were never apart from God, they have returned to their homeland, to what they believed was the land that had been given to them after they were liberated from bondage.

Coming home matters. Our traditions, our family ties, our identity are all sources of pride and wisdom to us. Like trees we are rooted in a heritage, and if we are pulled up in some way from that heritage, it takes a toll on the heart. If we manage to regain that connection, to plant our roots again, we often feel that we must cling ever tighter to what was once lost.

Refugees know this. Indigenous peoples in Canada know this. The Jews of the diaspora knew this. Anyone who lives abroad for an extended period of time knows this. Identity, especially cultural identity, helps us find our place in the world.

This is especially important when the world is unfamiliar or hostile to our identity. Those who find themselves immersed in a culture that says, “You are different. You are not a part of this family,†find solace and comfort in re-creating their own small enclaves of culture. Anyone who has ever been a part of any minority, subculture, or diaspora has experienced this.

This is something the Jewish people know very well. For generations, they were welcomed nowhere, except in their own set-apart group. It was not safe in these other empires. They were forced into hateful professions, pushed to sacrifice to gods that were not their own, scapegoated and willfully misunderstood. In the Medieval period in some European villages they were literally hunted like animals by groups of vigilantes.

In Jesus’ time they sometimes enjoyed some freedoms. The Romans respected the age of their religion, and made allowances that would not compromise their ritual practices. But they still lived occupied lives, and when they attempted to rise up, they paid in blood.

Living under the shackles of empire, carrying the burden of shared trauma, gives you two choices: give up and assimilate, or hold on to your roots as tight as you can. Here, the line between belief and principle becomes difficult to define.

Jesus comes home to his roots. He returns to the Galilee, to the people that would have watched him grow up. He comes to teach and they’re so happy that the home-grown boy has grown into such a pillar of their faith and culture. He’s a rabbi teaching in the synagogues. He has had mystical experiences in the wilderness that strengthened and deepened his faith. They feel pride. This is one of our own. We can claim him.

But then he comes to synagogue one morning, reads from the scroll, and something’s different. People can’t take their eyes off him. They’re waiting to hear his wisdom, and he responds that what they have become accustomed to only praying for has been fulfilled.

Imagine if one of our own read from this passage, and then told us all, here at St. Margaret’s in 2019, that Jesus has returned. Now, today. How would that feel? The first time you heard it, you’d probably think, “How inspiring!†You’d probably thank that person for preaching such a good sermon!

And then, suddenly, imagine that person saying, “I know where he is. He’s over there, doing salat prayers at the mosque.â€

…Oh that ain’t right.

We don’t get the whole passage from Luke. We get the inspiring part. Then things start to go sideways. The people are thrilled with Jesus, and “speak well†of him. But he responds by saying that he knows they are going to ask him to enact these prophetic words, to heal people and liberate them right there and then, in his own town. He tells them it’s not going to happen, because no prophet is accepted in his own town. Then he says,

“But the truth is, there were many widows in Israel in the time of Elijah, when the heaven was shut up for three years and six months, and there was a severe famine over all the land; yet Elijah was sent to none of them except to a widow at Zarephath in Sidon. There were also many lepers in Israel in the time of the prophet Elisha, and none of them was cleansed except Naaman the Syrian.â€

The response is…about what you’d expect.

In fact the worshipers are so angry that they form a mob, and the whole village attempts to throw him off a cliff.

To be clear, there is nothing about what Jesus says that is not squarely in line with the Judaism of his time. They knew those stories! They believed them! And they knew and believed the prophets when they wrote that eventually their God would call not only the Jews but all people to become a part of the beloved family, hearkening back to the covenant of Noah when all creatures were welcomed into the circle of God’s promise.

Few people like hearing the truth, but when we reach the point where our beliefs and our principles cannot be untangled from one another, it’ll be easier for us to pass through the eye of a needle than to hear the truth.

I don’t say this with judgement or anger. Despite our best efforts as so-called rugged individualists, we cannot help as a species but define ourselves in relation to others. We seek ourselves in the eyes of the other even as we push the other away. As people of faith, we are called to witness to a God who is so much incomprehensibly bigger than any one family or faith.

Since this is very difficult for us, we as Anglicans who believe in incarnation proclaim that God chose a form more comprehensible, easier to grasp: a person, a human being from a culture, from a family. He was fully embedded in that family, practicing the faith as he had received it and sharing nothing wholly foreign to it. And he reminded them – and us – that their god, our god, was bigger than Jerusalem, bigger than Rome, bigger even than ritual itself.

The people in Nazareth didn’t get it then…but a lot of other people who heard that message did.

“We don’t honour our parents by upholding beliefs but principles.â€

The belief is that God comes among us in certain ways, with certain faces, embodied and interceding with us according to prescribed ritual.

The principle is that God comes among us.

That could change everything. In fact, it already has.