Sep 12 | “And there’s another country” (Letters from the Coast)

St. Jude’s Anglican Home. The lunch table, with senior staff.

We all sit around, discussing our lives and the day. All of us are women/femmes.

The conversation suddenly shifts: “Hey…can you believe it’s been eighteen years since September 11th?â€

“No,†we all said, in a daze.

The stories came out – where we were, what we were doing, what we remember.

Only memories. No political commentary.

Sometimes I find it difficult to sit with these women because I’m so much younger than they are. My priorities and views are so, so different.

I would like to talk about how much I have changed since that day, politically.

But I don’t.

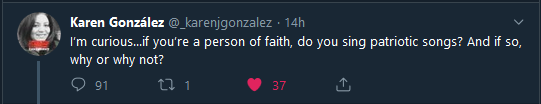

Today, images from childhood run through my head as I read through the replies to a tweet posted by Karen González, a Latina Mujerista theologian and author of The God Who Sees:

There were many responses, and a lot of diversity, but definitely a few themes emerged, and a few categories of folks.

First, there were folks who were unabashedly and uncritically patriotic, and saw their faith as an extension of their patriotism, an especially common attitude among a certain subset of American Christians.

Second, there were folks who were more critically patriotic, but did not see patriotism as antithetical to their own faith, or anyone’s. These folks would often use the language of, “I sing these songs in the hope that one day they will be true.â€

Third, there were folks who had once sung these songs, but no longer did, and most of them said this had been a fairly recent change, due to the current political climate. They often mentioned the uneasy mixing of patriotism and faith, or “civil religion.†Some of them said there were certain songs they would sing and others they would not. “This Land is Your Land,†complete with the more ‘prophetic’ verses, was cited many times as acceptable.

Finally, there were a few folks that said they never had, or made a change quite a while ago. One of them was a Mennonite, who said they would only profess allegiance to the Kingdom of God.

Another one was me.

I stopped singing the national anthem for the first time around 2011.

I wouldn’t say I had been a dedicated flag waver my whole life, but I spent quite a bit of it proud to be Canadian. I have scattered memories of singing the national anthem in both French and English – in fact, for the longest time, I didn’t even know the entire thing in one language or the other, but only a mishmash of both, with the first three lines in English and the next four in French. (It took me quite a while to realize how very VERY different the two sets of lyrics are). I seem to also remember singing both the anthem and “God Save the Queen†every morning in school when I lived in Ottawa, with accompanying music played over a loudspeaker as a precursor to morning announcements.

Ottawa was definitely a place where I felt encouraged to embrace my national identity: Canada Day on Parliament Hill, Laura Secord ice cream, learning French every day, Girl Guide trips into the woods to feast on pure maple syrup. When I came back to Vancouver, it didn’t feel quite the same, but I was still proud. I began to reclaim my identity as a West Coaster, somewhat disconnected and stone in love with nature.

In high school, we had a semester or two on “Canadian History†in Social Studies. I remember thinking it was the most boring subject I’d ever studied. I didn’t envy Americans their history (my ever-so-Canadian anti-American sentiments were really starting to bubble once I hit puberty and became more politically aware), but I did feel that surely more interesting things than fur trading and building forts had happened in the formation of Canada.

Probably the most interesting story we learned was about Louis Riel, so there was that.

So far as I know we didn’t really learn anything about pre-contact Turtle Island. And we did not learn anything whatsoever about residential schools.

I often tell people I learned about residential schools in church, because I did. When the referendum on the Nisga’a Treaty occurred in ’98 or ’99, I specifically remembering hearing in church that we should vote in favour of the Nisga’a, because we had done them wrong as a church and as a nation. I learned that the Nisga’a people had ties to the Anglican Church because our missionaries reached them first, and that we therefore today had a responsibility to advocate for them.

This was only five years after the Anglican Church of Canada offered its official apology to Indigenous peoples for its role in residential schools in 1993.

I also remember Bishop Jim Cruickshank, who had been present at my baptism, becoming Bishop of the Diocese of Cariboo, in which St. George’s Lytton residential school was located, and his work among the survivors there. Lawsuits and settlements eventually led the diocese to declare bankruptcy before it became first The Anglican Parishes of the Central Interior and then The Territory of the People. When I interviewed him for an ethics paper in seminary, he told me he had been glad that the diocese had declared insolvency. This was the work of the Kingdom, he said, dying so that others might live.

I do not remember ever thinking Indigenous Peoples were entitled or lazy or stupid or drunk, even though I’m sure I heard people say it off and on. I don’t say that to aggrandize myself; it’s just true. I had arguments with friends who would say racist stuff against them from an early age. My great sin was assuming that they were outliers, that truly reasonable people knew that white people had done wrong to Indigenous Peoples and that we had a responsibility to build a better relationship today.

Imagine my surprise when I discovered this was a minority view, and often still is. Again, I don’t say this to aggrandize myself. It was my privilege that led me to believe most people shared my views. It took me time to realize how bad things still were.

In 2010 or 2011, I took a mandatory class at seminary on Canadian History. It mostly focused on the church’s presence and activities during the formation of Canada, but of course we had a hefty chunk of time dedicated to learning about the residential schools.

About forced separation from families by the RCMP, on pain of incarceration.

About hunger experiments and malnutrition driven by simple apathy.

About dental surgery occurring on cafeteria tables without anesthetic.

About rampant tuberculosis and other diseases.

About abuse: physical, emotional, and sexual.

About children beaten for speaking the only languages they knew.

About the Bryce report, and how the government knew exactly how bad it was, and didn’t care.

About how the last one closed in 1996, when I was twelve years old.

I stopped singing the national anthem for about a year.

My husband asked why.

I said, “I can’t. I can’t support this country when I know what we’ve done. We’re not even a legitimate nation. We came uninvited and built ourselves on greed and violence, and we continue to perpetuate it.â€

He couldn’t understand it. We argued about it for a long time.

Finally, one day at a soccer game, I relented, and told him I supposed I could sing in hope for the things in the song.

He gave me a side hug and said, “That’s it.”

I sang it again a few times after that.

But around the time of the Colten Boushie and Tina Fontaine acquittals, I stopped singing again.

And today, I flat refuse.

I’ll stand, because if I don’t, in the current political climate, I’ll likely experience harassment and violence.

But I won’t sing.

God is the owner of my voice and my heart. Not the state, which murders and rapes and oppresses and crucifies.

I refuse to glorify a nation founded in blood that continues to violate and destroy and lie and steal.

I refuse to make professions of unity and “standing on guard†when I know they are empty.

I refuse to pledge citizenship to any country other than the Kingdom of God, which is beyond nationality or borders. Sure, it has its own baggage, but that’s only because of the incapacity of the colonial mind to imagine such a glorious, wonderful thing as a nation born through love rather than hate and greed.

I don’t judge other people for doing what their conscience thinks is right. But I can no longer reconcile my own faith with any act of earthly patriotism. To me, patriotism is antithetical to Christianity. The Anabaptists got it right.

Around the same time I stopped singing a couple of years ago, my husband and I revisited the conversation.

I remember he looked so weary.

I’m not entirely sure, but I don’t think he sings anymore either.