Nov 13 | “Called to be Saints” – (Philippians Group Presentation, November 12th)

Quick background: One of the tasks given to me at St. Philip’s (where I am currently an intern) was to lead a talk on saints and to introduce in particular the six Celtic saints depicted in beautiful stained glass on the church’s southern wall. The talk was held at 4pm so we could still catch the light. Here are my notes from that talk.

What kind of words do you think of when you think of ‘saints?’

(We recorded the following words from the group: Halo, good, grace, faith, us, stewardship of creation, prayer, comfort, humility, grandmother, perfection, and meekness; and then the names of several saints including David, Mary, Michael, Martin, and Elfrig).

Let’s invite the Bible to our conversation. Now the Bible has its own words, although obviously not in English. The English word “saints†appears in several translations. It is sometimes used as a translation of the Hebrew word חֲסִידָיו֙ (hasidaw) in the Hebrew Bible. This means “holy ones†or “godly ones,†or, in the case of the song of Hannah who was mother of the prophet Samuel, “faithful ones.†And it’s always used after a possessive – it’s always in reference to God, and ownership by God.

BELONGING TO GOD

The Greek word most often translated as “saints†in the New Testament is á¼Î³Î¯Ï‰Î½ (hagiÅn). It means the same thing: “holy ones.†And what’s really interesting is that the word only shows up in one Gospel: Matthew tells us when Jesus is crucified, the curtain of the Temple is torn in two, there’s a big earthquake, and the bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep are raised and get up and walk around. So zombies? Probably meant to say something about how a new era has begun, post-crucifixion.

SIGNS

The person who really gets some use out of that word hagiÅn is Paul – it comes up in a ton of his letters and the ones attributed to him. It also comes up in some of the other epistles like Hebrews and Second Peter. And someone else who uses it everywhere is the writer of Revelation. His view of the holy ones is apocalyptic and mystical in appropriate Revelation style.

INSTRUMENTAL TO THE KINGDOM

Â

So in light of all that, how do you feel when Paul says that the Church at Corinth – and, let’s not kid ourselves, WE – are called to be saints?

(Most people said a variant of “Scared.”)

Fear not. The core meaning of these words hasidaw and hagiÅn, their concept of holiness is actually not about being “good,†necessarily, or even “righteous.†It actually has more to do with being “different.â€

DIFFERENT

Another word that gets used a lot in Hebrew Scripture is “set apart,†or “distinct.†It’s not about necessarily being more special, or cut off from other folk. We’re meant to understand this as something that’s “not for everyday use,†like how you wouldn’t use one of our communion chalices to pour the tea we’re drinking. We use the chalice for a different purpose. This concept of being “set apart†comes up in Scripture a lot: Joseph is “set apart†from his brothers; the firstborn is “set apart†for the Lord when the great covenant is being made in Exodus. Setting things apart is usually set alongside some form of agreement or covenant. It’s paradoxical – a relationship and yet a separation.

RELATIONSHIP / SEPARATION

Now again, if you’re worried that this is supposed to cut a person off from the regular world, that’s not a full understanding. That’s why the lives of the saints are so important – in Anglican tradition we believe that people becomesaints through the actions they do in their earthly lives. And this relationship isn’t just about God, but each other. You’ll notice in the Bible, we never discuss saints in the singular. It’s always plural.

CLOUD OF WITNESSES

Â

Now in the Bible, that’s all we get of the saints. We have some miracles and we have the characters who eventually became saints in our tradition – the Apostles, the martyrs and such – but they’re not explicitly named saints. The saints are usually referred to in the third person, and then we have these descriptors.

So beyond that, what do saints look like in the rest of our traditions? Let’s take a look at some of the ones we have here at St. Philip’s to flesh this out a little.

AIDAN

This is Aidan of Lindisfarne. We celebrate him on August 31st. He was Irish but is often called the Apostle of Northumbria. Aidan became a bishop during a time when the Christian king Oswald was trying to return Christianity to Ireland after Anglo-Saxon paganism had undergone a resurgence. Oswald chose to send missionaries from the monastery of Iona rather than the Roman controlled monastery in Northumbria, and Aidan picked up where an earlier ineffective bishop left off. He founded the monastic community of Lindisfarne, which produced the stunning illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels. He also made a point of travelling on foot to many different villages, freeing slaves and giving money, room, board, and education to orphans. His model of mission involved conversing with locals face-to-face and taking an active interest in their lives. He also dined with the rich, and distributed the excessive gifts they often bestowed upon him to the poor and slaves. He was a friend of the poor and friend to the rich, and died leaning against the wall of a local church on one of his missionary trips in the seventeenth year of his episcopacy. Bishop of Durham Joseph Lightfoot claims, “Augustine was the Apostle of Kent, but Aidan was the Apostle of the English.â€

BRIGID

Here we have Brigid of Kildare, one of Ireland’s patron saints, affectionately known as Mary of the Gael. There has been some controversy over whether or not she was a real person. One art historian believes that the traditions of the mother goddess of a form of Celtic paganism, who was also named Brigid, have been grafted onto this figure. The first clue to that claim is that Brigid’s celebrated on February 1st, which is the date of the pagan feast of Imbolc, or the first day of spring. A second clue is this symbol: You might recognize this as the cross of St. Brigid, which may be related to an earlier pagan symbol for the sun. The Apostles of Ireland were clever in appropriating the culture of the land for their purposes, and there are a few common adaptations of pagan symbols and legends to ease the transitions between religions. Whatever their motives were, it became a part of the land’s traditions. Now St. Brigid’s crosses are made every year and have traditionally been thought to protect the house from fire.

The real Brigid may have been born in Dundalk, County Louth. Although the biographies differ, they seem to agree that one of Brigid’s parents was a slave. Several of the accounts claim that she performed miracles as a child, particularly for the benefit of the poor. Eventually, she was committed to the religious life, and granted abbatial powers. She established an oratory at Kildare which became a centre for religion and learning, soon developing into a cathedral city. She then established two monasteries and a school of art, including metalwork and illumination. She was apparently very good friends with St. Patrick, with the Book of Armagh stating that they had “but one heart and one mind.†There have been many more miracles attributed to her as an adult, most of them to do with healing and domestic tasks.

COLUMBA

Columba’s feast day is June 9th. He was born in Ulster and trained under St. Finnian with twelve others who eventually became known as the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. He eventually entered the monastery of Clonard and as Wikipedia so poetically puts it “imbib[ed] the traditions of the Welsh Church.†He is described further by author John Crawley as “a striking figure of great stature and powerful build, with a loud, melodious voice which could be heard from one hilltop to another.†Apparently he was a bit of a troublemaker too, as he got involved in quarrels with other monks and even induced one clan to battle a king when the king had violated a prince’s right to sanctuary with Columba. Excommunication was threatened but later lessened to exile, and he resolved during that time to win as many souls as possible for Christ. He traveled to Scotland, bringing Christianity to the Picts and other tribes up the west coast, and founded Iona, which became a dominant religious and political institution in the region for centuries. He guided the region’s only centre for literacy, wrote several hymns, and transcribed as many as 300 books. He was also appointed a diplomat among many of the tribes. In the Vita Columba we have accounts by the author of Columba’s prophetic revelations, miraculous works, and apparitions of angels.

HILDA

Hilda of Whitby had a high-class upbringing, as her father was related to Edwin of Northumbria. She was appointed Abbess of Hartlepool Abbey by Aidan of Lindisfarne. Eventually she founded Whitby Abbey and remained until her death. Five men from her monastery later became bishops, and two joined Hilda in sainthood. Hilda’s feast day is November 17th.

The Venerable Bede describes Hilda as a woman of great energy, who was a skilled administrator and teacher. She gained such a reputation for wisdom that kings and princes sought her advice.My favourite story about her is her support of Cædmon, however. He was a herder at the monastery, who was inspired in a dream to sing verses in praise of God. Hilda recognized his gift and encouraged him to develop it. Bede writes, “All who knew her called her mother because of her outstanding devotion and grace.â€

She suffered from a fever for the last six years of her life but didn’t let it stop her from founding another abbey at Harkness in her last year. Legend says that the moment she died, the bells at Harkness told. Legend also has it that sea birds flying over the abbey dip their wings in her honour.

BEDE

You might remember him from high school English. He might sound more familiar as “the Venerable Bede.†He is the only native Briton to achieve the title ‘Doctor of the Church,’ which he received in 1899 from Pope Leo XIII. He was born in Sunderland on the land owned by the twinned monasteries Monkwearmouth and Jarrow, and was likely from a noble family. You can see he’s standing next to Cuthbert and this is because they had a connection in life; Cuthbert was one of Bede’s disciples. He became a scholar and started to write around the age of 29. He is best known for his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, which gave him the title “the Father of English history,†but he also wrote poetry and apparently was a gifted singer as well. He is buried in Durham Cathedral. His feast day is May 25th.

CUTHBERT

He was another Northumbrian saint, the patron saint of Northern England. He was likely born of a noble family in what are now the Scottish borders in the mid-630s and decided to become a monk after having a vision of St. Aidan being carried up to heaven by angels and then learning that Aidan had died that night. Cuthbert grew up and came of age during a time of conflict between Roman and Irish traditions in the church, which shaped his views. Though Cuthbert himself was educated in the Celtic tradition he accepted Roman traditions without much bother. He became famous and beloved among the people for his missionary trips, miracles, and his charm and generosity to the poor. For a while he lived a contemplative life as a hermit before being elected Bishop – under great reluctance on his part. He was only Bishop for about a year before returning to Northumberland to his cell and dying after a painful illness. He was buried at Lindisfarne the same day but through a series of escapes from marauding Danes his remains eventually came to rest at Durham Cathedral. His feast day is March 20th, although our Episcopal brothers and sisters down South celebrate him on August 31st.

So here are some of our brothers and sisters in faith. I see them as living into many of the words we have here. But can we live up to this?

(Someone outright said, “No.”)

Don’t worry. It’s a trick question.

It’s not about living up to an expectation in order to earn your wings. It’s about integrity – not simple truthfulness and a goody-two-shoes “saintly†bearing. It’s not even about being saved.

It’s about turning around and seeing the sunrise that has already begun, and running into it.

At a certain point, miracles don’t matter. Even an exemplary life is something that’s great but not required. How does the saying go? “All may, some should, none must.â€

What does matter, in a very general sense, is recognizing the great gift of life you and the entire cosmos have been given. In a Christian mindset, it is discovering and beginning your baptismal ministry and making it determine your truth and your actions.

It’s the work done by love for love by our friends in the places where they were living that made them saints. It was not about miracles. It was about saying “Yes.â€

This also must be balanced with the humility that God in Christ is working already in every corner of the world, and was doing so even before any of us saw it happen. We don’t need to join in, but it’s so much more beautiful when we do, because then we are participating in the mystical work of the already/not yet kingdom.

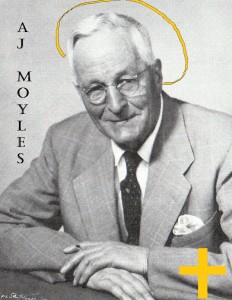

That’s why I brought this. Here is one of our saints: St. A.J. Moyles of Dunbar Heights. We can giggle, but I’m actually being quite serious. He was one of the founders of this parish. He did many good things and gave us the community we enjoy today. God was already weaving miracles in Dunbar Heights before we got here. We just wanted to testify to it.

That’s why I brought this. Here is one of our saints: St. A.J. Moyles of Dunbar Heights. We can giggle, but I’m actually being quite serious. He was one of the founders of this parish. He did many good things and gave us the community we enjoy today. God was already weaving miracles in Dunbar Heights before we got here. We just wanted to testify to it.

Anyone can be a saint – from this man and those who worked with him, who gave us so much, to the ungrateful rabble at Corinth. It’s not about being good enough to become a saint. It’s about living into an identity that has already been given to you.